Large, beautiful, vegetated dune in northern Morocco. Plants serve as a major part of the ecosystem here providing food for birds and small mammals.

Photo: Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines

Contents

Dune vegetation on Indian Beach, Bogue Banks, NC.

Photo: Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines

Plants and the beach

Aside from the striking natural beauty that plants provide, they are crucial parts of beach ecosystems. Plants are among the first forms of life to inhabit beaches and dunes. Once plants have taken root, sands begin to stabilize, slowly at first, then faster as more plants take root. Plants serve as habitat for many animal species from providing basic shade to providing nest material or even allowing a home to be built inside them. They offer camouflage to animals and are a primary food source for some. Without plants, beaches would probably be devoid of animal life.

Beach vines

Railroad vine, or bay hops (Ipomoea pes-caprae), is an important vine that stabilizes beach dunes with runners that can reach lengths of over 30 meters. This specialized morning glory can survive in drought, extreme heat, and very salty areas without problems. Without this plant, dunes would keep shifting location on the beach making the areas inhospitable to animals. But once this plant anchors the sand and begins to grow, other species such as sea oats, birds, and crabs are much more likely to thrive. Birds can make their nests between the runners and be camouflaged from predators. Other plants that require more stable soils can also move into areas where railroad vine lives stabilizing the dune even more. Stable dunes serve not only as wildlife habitat, but protect buildings and roads that may have been built too close to the ocean. This particular beach vine lives in the United States, but similar species perform similar ecosystem functions all over the world.

Beach grass

Sea oats (Uniola paniculata) is an important plant species that stabilizes shifting sand dunes. Blowing sand is trapped by numerous stems of the plant. When sea oats are buried by shifting sand, the plants stops growing upward and instead grows horizontally just under the surface of the sand. This sometimes results in deeply buried underground stems that also help stabilize dunes. Because of this plant’s importance, it is protected in many areas; in Georgia and Florida (US), it is illegal to pick sea oats.

Birds and the beach

Beaches support an amazing variety of bird species from small sand pipers to large pelicans. Many birds spend large portions of their lives over the water, but they all must eventually come out of the air to find a mate and reproduce. The sand, rocks, pebbles and plants of the world’s beaches serve as breeding grounds for many species of bird. Preservation of beaches as nesting sites is crucial for the protection of bird species. When beaches are developed, polluted, or destroyed, habitat critical to the life cycle of all of these animals is also destroyed. Beach sand mining is a major mechanism for habitat destruction. Below is some information on just a few species of birds that call the beach home.

Seagulls

It is hard to take a trip to the beach without seeing seagull like the one pictured here from Montery Peninsula, California.

Photo: Wikipedia user Dschwen

Gulls are probably the animal people associate most with the beach, but many people know little about seagulls. These birds are extremely maneuverable able to hover in the slightest of winds and dive with amazing speed. There are over 50 species of seagulls ranging in size from about 30 cm to 75 cm with wingspans over 1.7 meters. Gulls are aggressive and will display such aggression when they are threatened. They scavenge for their food of crabs and fish and will steal food from their own species or others whenever possible. Gulls nest on the ground making habitat loss a major threat to their existence. Beach sand mining and development are among the worst threats to gull habitat. Although most gulls species are found in abundance, some species such as Olrog’s Gull and Saunders’ Gull are threatened with habitat loss as the single greatest threat. Other species are well adapted to life away from the coast with a few species prospering in garbage dumps. The abundance of these species camouflages the low numbers of other species perpetuating the myth that gulls will never run out of habitat. This is wrong. Beaches need to be protected to ensure the future of all gull species.

Plovers nest on the ground. Their speckled eggs are camouflaged making them hard to see, even for people walking on the beach.

Photo: Richard Kuzminski

Plover on a beach with heavy recreational use and driving.

Piping plover

The piping plover (Charadrius melodus) is native to the beaches of the North American Atlantic coast and the West Indies in the Gulf of Mexico. The plover is threatened in the United States and endangered in Canada. As a result, some efforts have been made to protect its habitat. This protection, however, would not be necessary if beaches were undeveloped or significantly less developed. In some areas, protection measures have been of limited benefit to the bird, while measures in other areas have been successful. Examples of protection measures range from protecting individual nests (located on the ground) to closing entire sections of beach.

The plover feeds on insects, worms, and crustaceans abundant in beach debris or wrack lines. It is a medium-sized bird with adult body lengths of around 17 cm and wingspans of up to 45 cm. It winters in the southern part of its range and returns to northern climes for breeding in the spring.

View a beautiful slideshow on the Piping plover.

Pelicans

Pelicans live on every continent except Antarctica even though there are only about six species. This means that the bird is very well adapted to different conditions. One adaptation that pelicans share is the large pouch or gullet used to capture prey, usually fish. Another adaptation is the birds ability to live in a variety of conditions. For example, the American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) lives inland much of the year and winters on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. These large birds with wingspans of over 3 meters must eat over 1.5 kg of food per day.

The Great White Pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus) lives in Africa, Europe, and Asia. The bird frequents beaches in search of fish, crustaceans, and other small organisms on which to feed but lives most of its life on inland bodies of water.

Brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) are different from White Pelicans because Brown Pelicans live only on the beaches of North and South America making beach habitat crucial for the bird. Brown Pelicans were on the endangered species list in the United States for 40 years and only recently have been candidates for removal form the list. Brown Pelicans are much smaller than white ones but are still large birds. Wingspans are around 2 to 2.5 meters for brown pelicans.

Gentoo penguins (Pygoscelis papus) on King George Island.

Photo: NOAA/Vents, Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI)

Penguins

There are about 20 species of penguins, but only four species, the Adelie, the Emperor, the Chinstrap and the Gentoo, live on Antarctica. There are no penguins at the North Pole. The remaining species of penguins live in the southern hemisphere in Australia, New Zealand, Africa, and S. America with the exception of the Galapagos penguin, which lives near the equator. The Galapagos penguin thrives so far north because of the deep, cold-water Humboldt ocean current. All of these flightless birds spend their time in the cold ocean water and on the beach. Beaches are necessary for the penguins to make nests and lay their eggs. Without clean beaches, penguins all over the world would have difficulty surviving.

These curious, flightless birds are somewhat awkward on land, but in the water are extremely agile and adept swimmers. Larger species can dive to depths of over 500m and hold their breath for 15 minutes! Most penguins lay two eggs, but species in colder climates usually lay only one egg. The egg is small compared to the size of the mother. Penguins range in size from the 40 cm Little Blue penguin to the Emperor which can reach 1 m.

Terns

A Caspian tern (Hydroprogne caspia) photographed near Kemah, TX.

Photo: Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines

The birds that resemble seagulls but have orange beak are called terns and are related to sea gulls. Many species of terns have grey or black coloration on their heads too. There are over 40 species of terns and they live on every continent of the world. Terns generally eat small fish (which they spot while hovering over the water), bugs, or other small invertebrates. They range in size from the 22 cm long Least Tern (Sternula antillarum) to the 48 cm long Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia).

Caspian terns (Hydroprogne caspia) are the largest terns in the world with wingspans of up to 140 cm and the most widely distributed tern; they are found on every continent except Antarctica. Like other terns, they hover over the water in search of fish. When they see one, they quickly dive by tucking in their wings. The beach is important to terns for nest sites. Without the beach, the terns wouldn’t be able to find suitable sand, gravel, and vegetation to lay their eggs.

The Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea) goes to the ends of the earth every year. It spends the summer of the southern hemisphere on Antarctica and then flies back to the Arctic Circle to breed during the northern hemisphere summer. This flight of over 18,000 km each year makes it the largest migration of any animal on earth! The Arctic Tern needs beaches for nesting sites. The birds dig shallow pits called scrapes in the sand or gravel laying 1-3 eggs. When they hatch, the young birds must learn to fly quickly for their long journey.

Other beach animals

Crabs

There are over 6,500 known crab species making them an extremely diverse group of animals. Crabs are covered in a hard exoskeleton which offers them protection from predators. As a group, they are scavengers with some species eating just about anything: algae, mollusks, worms, crustaceans, fungi, and other organic material. Crabs are an economically and culturally important species in many countries such as Japan and China. Crab habitat varies; some species live exclusively in the ocean in a range of water depths with a preference for shallow waters while some species live entirely on land. Some land species have structures that function as primitive lungs. Habitat loss is a major threat to many crab species as well as invasive and non-native species. Beach development, nourishment, and dredging produce fine sediment which is harmful to crabs as well.

Are hermit crabs true crabs?

Hermit crabs are not very closely related to true crabs and live in shallow salt water in most areas of the world. This includes most beaches of the world meaning that beach destruction also threatens these tiny creatures too. There are about 500 species of hermit crabs. Hermit crabs can not make their own shells and crawl into shells from other sea creatures, most often sea snails. In order for the hermit crab to increase in size, a vacant shell must be available. If no shell is available, the hermit crab will not grow very quickly.

Crabs that we eat have an exoskeleton that they make themselves and are a much more diverse group than hermit crabs. There are over 6,500 species of true crabs and range in size from the Pea crab to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span of over 4 m!

Sea turtles

Sea turtle on Kauai, Hawaii, USA.

Sea turtle tracks on the beach near Fort Morgan, Alabama, USA.

Loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta)

This loggerhead turtle has had a tracking device attached to its back. The device will not interfere with the turtle’s ability to survive.

Sea turtles are found in every ocean of the world except the Arctic Ocean even though there are only 7 species. All 7 species are threatened and 5 of them are endangered or critically endangered. These amazing swimmers are very similar to their ancestors and haven’t changed much in over 10 million years. Among their adaptations are their highly evolved front flippers, ability to hold their breath for long periods of time, and hard shell. They are the only reptiles with a hard shell and some can live up to 80 years and weigh over 500 kg!

There are numerous human threats to sea turtles. The shrimp industry represents the largest threat because turtles that end up caught in the long fishing nets usually die (see photo). Another threat is illegal poaching and harvesting of eggs and turtles for food. Turtle skins and shells are also used in arts and crafts. In some cultures, turtle eggs are believed to be an aphrodisiac. When traveling, do not support these industries and do not purchase souvenirs or goods made from these animals. Beach sand mining also represents a major threat to sea turtles. Beach sand mining in St. Lucia was extensive for the concrete industry until a moratorium was issued in 1984. A decade later in 1993, the beaches still had not recovered as turtles had to abandon nesting attempts when they hit the water table.

Sea turtles and beaches

Sea turtles use beaches as nesting sites for incubation of their eggs. Without nesting sites, it would be impossible for sea turtles to complete their life cycle. They spend much of their time eating sea grass and when the females are able to reproduce, they return to the beach to lay their eggs. In most cases, the females return to the beach where they were born using the earth’s magnetic field to navigate. Once on the beach, they lay large clutches of eggs in shallow pits of sand where the young turtles mature. It takes around two months for the young turtles to mature. When the turtles finally hatch, they must crawl to the ocean quickly to avoid predation by birds, other animals, and human threats.

Loggerhead sea turtles

Loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) live in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans and reach up to 350 kg. Loggerheads have reddish brown shells and lighter skin. They are an endangered species meaning that the turtles are at risk of becoming extinct. Fishing nets, dredging sand off the ocean floor, and coastal development all threaten turtles and their habitat. If you spot a sea turtle in North America, it is probably a loggerhead because they are the most common turtle there.

Loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) live in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans and Like other sea turtles, the beach is necessary for loggerheads to survive. Loggerheads make their nests on the beaches of the Atlantic Ocean in the United States and in the Mediterranean Sea, usually laying between 75 and 150 eggs. If they survive the first few years of their lives, some may live to be over 75 years old!

Large male seal on an Australian beach with a harem of females on the left.

Seals

These playful swimmers live all over the world and are intimate with our world’s beaches. They are extremely well suited for life in the water with adaptations such as powerful tail muscles, warm blubber, and the ability to conserve oxygen on long dives. They feed in the water, but need beaches to breed, raise young, and reproduce. One the beach, they are also less exposed to predators like sharks.

What exactly are seals?

Seals are part of a group of animals called pinnipeds meaning “winged feet,” which refers to their flippers. There are over 33 species of pinnipeds with three main divisions: true seals, seals with ears, and walruses. The true seals are more adapted to live in the water and can’t “walk” on their hind flippers like the eared seals can. Pinnipeds are excellent swimmers and can hold their breath for almost 2 hours! They can do this by slowing their heart rate when they dive and changing the chemistry.

The beach is important to all pinnipeds for breeding and raising their young. Seals leave their young alone on the beach during the day while feeding. The mothers return at night to nurse their young. People often mistake baby seals as “orphans” on the beach that have been left by their parents, but this is not the case. Baby seals are sometimes left for days at a time while the mother is feeding. The best thing to do is to call local wildlife officials and remember that handling baby seals is illegal.

The white cliffs of Dover are an example of a rock formation made up of tiny fossils of cocoliths, single-celled organisms living in the oceans of the world.

Photo: www.flickr.com/people/fanny

Microfossils

Microfossils are fossil that usually are smaller than four millimeters. From the White cliffs at Dover to the chalk caves of the Champagne region of France, these tiny fossils are found all over the world both on the coast and inland. Huge populations of tiny organisms with hard shells made of silica or calcium live in the world’s oceans.

When these organisms die, their shells can become fossils and remain for very long periods of time. Although these organisms are very small, the fossilized remains of them can accumulate in huge quantities for two reasons:

- there are so many of them, and

- these groups of organisms have accumulated for millions of years.

When ocean temperatures are favorable for their life-cycles, deposits of their bodies on the ocean floor can reach amazing depths – hundreds of meters! These fossilized remains are referred to as oozes and there are two main types of oozes: calcareous (calcium-based) oozes and siliceous (silica-based) oozes.

Calcareous oozes

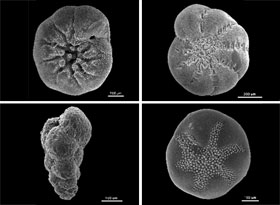

Calcareous oozes, or calcium-based oozes, are made up of the shells of foraminifera (forams) and coccolithophores.

Forams are single-celled organisms that live only for about one month. These protists are very small, but they are very large in number: tens of thousands of species of forams live in the waters of the oceans. When forams die, their shells settle on the ocean floor and accumulate. Forams are very useful for dating rock layers since scientists have good data about which species of forams lived during particular time periods.

Coccolithophores are single celled organisms with shells made up mostly of calcium carbonate plates. When cocoliths die, their shells accumulate on the ocean floor. During the Cretaceous period some 145 million years ago, the oceans were warmer and cocoliths accumulated for very, very long periods of time. You probably are quite familiar with cocolithic rock, but you might not know it; chalk is an example.

Siliceous oozes

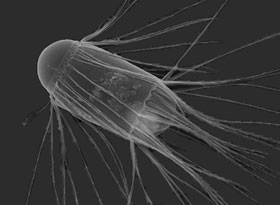

This diatom is dangerous to fish and aquatic life because of the long spikes that can get caught in their gills.

Photo: NOAA

Siliceous oozes are made up of the shells of diatoms and radiolarians.

Diatoms are a type of algae, most of which have one cell. There are a few hundred species alive today, but there are over 100,000 fossil species! These tiny algae use sunlight to make energy and account for nearly half of all the energy producing activities in the world’s oceans (primary productivity – mostly through photosynthesis). Like the other oozes, when diatoms die, their small silica shells sink to the bottom of the ocean and slowly accumulate.

Radiolarians are a group of amoeba with a hard shell made of mostly silica. Like the other oozes listed above, the shells of these organisms accumulate on the ocean floor. You might know the word diatom if you have ever used soil with diatoms mixed in called diatomaceous earth. Other uses include pool filters, to clean up spills, and as an abrasive. It’s a good things that we use diatoms for so many things – their silica shells never biodegrade!

Insects and Worms

In addition to larger plants and animals, beaches are also full of much smaller forms of life. Insects are present at virtually all beaches and provide important ecosystem functions such as breaking down organic matter, nutrient cycling, and serving as food sources for larger organisms. Many people only consider insects when their presence is in some way objectionable to their visit to the beach, such as mosquitoes, but these tiny creatures have some amazing adaptations that suit them to life on the beach. To find some insects on your beach, gently roll over some of the organic matter from the wrack line and look closely. Little is known about many of these species; who knows what you might find?

Northeastern beach tiger beetle (Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis)

Photo copyright: Steve Collins. Used with permission.

Northeastern beach tiger beetle

The Northeastern beach tiger beetle (Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis) is a beetle that, true to its name, is found on beaches in the northeastern United States. Historically, it was found in every coastal state from Massachusetts to Virginia. Today, it is extirpated (or locally extinct) from Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey, with a small population remaining in Massachusetts and a larger population in the Chesapeake Bay. It is listed as endangered in Massachusetts, and threatened federally.

The ideal habitats for northeastern beach tiger beetles are long, wide, undisturbed, dynamic beaches. In the summer months, larvae live in the upper intertidal zone, and dig burrows up to 14 inches deep. Adults live between the dunes and the high-tide line. From about November to March of each year, larval northeastern beach tiger beetles overwinter up high on the beach, avoiding most waves and storm activity. After their hibernation, they will emerge and move back down to the intertidal zone.

Northeastern beach tiger beetles are handsome, sand-colored insects. Specifically, they are a whitish-tan color with dark markings and a green-bronze head. They are between ½ and ¾ inch long, with long slender legs and large pinching jaws. To catch food, larvae wait near the top of the burrow for small invertebrate prey to get close. Then, as “tiger-like” skilled predators, they grasp their prey (often lice, fleas, and flies) in a quick and aggressive manner, hence the name “tiger beetle.” Once they emerge as adults, they can fly for up to a mile to find a more hospitable habitat or to scavenge for food such as dead fish and crabs for feeding.

Presence of the Northeastern beach tiger beetle is an indicator of a healthy beach.

California Beach Hopper (Orchestoidea californiana)

Photo copyright: Peter Bryant, University of California, Irvine. Used with permission.

Beach hoppers

Beach hoppers, or sand fleas (Orchestoidea spp.), are common to the west coast of North America and are one of the most abundant beach insects. Relatives of the beach hopper can be found around the world. They spend most of the day buried head-first in the sand trying not to get carried away by the tides and most of the night feeding on kelp, other organic debris, and microorganisms living in the sand. If high tide does come at night when they are feeding, they take a break for several hours and burrow into the sand so they don’t get swept out to sea. Move a pile of kelp on the beach, and you are likely to send hundreds of these tiny creatures hopping. Beach hoppers need sandy beaches for habitat, but are one of the few insects from the Amphipod order that require sandy beaches: nearly all the other Amphipods live in the ocean.

Kelp fly (Fucellia rufitibia)

Photo copyright: Peter Bryant, University of California, Irvine. Used with permission.

Kelp flies

Several species of kelp fly live on the beaches on the west coast of North America and many more live around the world. These insects are responsible for cycling nutrients through the beach ecosystem and serve as a source of food for a variety of other animals. Kelp and seaweed wash up on most beaches and this decomposing organic matter serves as an ideal habitat for kelp flies.

Rove beetles

Intertidal Rove Beetle (Cafius sp.)

Photo copyright: Peter Bryant, University of California, Irvine. Used with permission.

Beetles are everywhere, including at the beach. The Beetle family (Coleoptera) is the largest family of animals on earth; over 350,000 species have been described with an estimated millions more undescribed. The rove beetles are a large portion of the beetle family with members living in nearly every conceivable habitat except the arctic regions. Rove beetles that live in beach sand have the ability to survive submerged for periods of time enabling some species to survive a high tide and then come out to feed when the tide recedes. Rove beetles feed on kelp fly larvae and pupae and other amphipods.

Worms

Beach sand seems like an unlikely place to find worms. The soil has little organic matter compared to soils away from the coast, the salt content can be very high, and moisture levels change dramatically as the tide changes. Despite all of these conditions some worms have adapted through time to thrive here.

Bloodworms gain enough nutrients for a successful life from eating bacteria and algae on grains of sand.

Photo copyright: Peter Bryant, University of California, Irvine. Used with permission.

Blood worms

Blood worms from the genus Euzonus live all over the world, often in huge numbers. The fossil record shows a wide variety of species throughout history and a new species was observed in Japan in 2003. These specialized worms usually live in the top 20 cm of sand where oxygen supplies are plentiful in the intertidal zone. These amazing worms eat sand to gain nutrients from bacteria and algae living on the grains of sand. Imagine being able to survive from eating sand! They get their red color from red blood cells, the same kind that humans have, which enable them to live in low oxygen environments.