Trash

July 13, 2024

Using Trash to Track Other Trash – Hakai Magazine

Excerpt:

An Australian organization is taking “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” to heart with its ghost net clean-up program.

Australia’s vast coastline is littered with marine debris. From burst balloons and countless straws to plastic drink bottles, styrofoam, and fishing lines, all sorts of trash ends up on the country’s beaches, and Heidi Tait, cofounder of the nonprofit Tangaroa Blue, has combed through it all. But as the old adage says, some trash is actually treasure—provided you look at it from the right perspective. In this case, Tait and the Tangaroa Blue volunteers working to clean up Australia’s beaches unexpectedly accumulated a trove of strange tire-shaped capsules scattered along the Cape York coast, near Australia’s northeastern tip.

When Tait and her teammates started finding the capsules washed ashore, they weren’t quite sure what they were looking at. But by busting one open, looking at the company names listed inside, and making a few calls, Tait eventually connected with Satlink—a Spanish satellite communications company. Satlink’s GPS-enabled buoys, the ones the beach cleaners kept finding, help commercial fishers track their nets, lines, and other gear.

Tait’s partner, Brett Tait, Tangaroa Blue’s circular economy developer, had a brainwave that would see the buoys not just recycled but reused.

For more than a decade, boat crews working farther west, in Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria, had been telling the Taits about how abandoned fishing nets were circling the gulf, ensnaring and strangling sea turtles and dugong. These so-called ghost nets had either broken free from commercial fishing vessels and gotten lost, or were cut loose by fishers after getting snagged on rocks. Weighing a few tonnes each, the nets that boat crews had chanced upon in the gulf were often too big for them to heave out of the water. They’d typically report the finds to the authorities, but by the time anyone with an appropriately equipped vessel could head out to retrieve one, the mass of tangled rope had often vanished from sight…

Perhaps, Brett thought, Tangaroa Blue could solve the problem using their newfound GPS buoys. The trackers are “such a high-tech piece of equipment,” Tait says. They’re obviously not cheap, and for them to go to a landfill “seemed like such a waste.”

So, in December 2022, Tangaroa Blue started handing the buoys out to its flotilla of local partner crews: boat charter operators, commercial fishers, Indigenous rangers, and national park service members who had agreed to carry the repurposed buoys. When these teams come across a ghost net they can’t haul in, they hook one of the GPS-enabled floats onto it. Once attached, the tracker pings its location every few hours. A web portal lets Tangaroa Blue monitor the nets’ movements and alerts the organization if one is drifting dangerously close to a coral reef or shipping lane…

Also of Interest:

In Graphic Detail: Gluts of Ghost Gear

Elena Kazamia | Hakai | 03-08-2024

Plastic haunts the ocean. Every year, a gargantuan heap of fishing equipment—mainly made from plastic—is lost, abandoned, or discarded at sea. That neglected fishing paraphernalia, known as ghost gear, can persist in the environment for hundreds of years, killing all kinds of marine life. While scientists have long been aware of the threat ghost gear poses, updated research gives detailed estimates on the shocking amount of derelict gear lost at sea.

In academic literature and institutional reports, researchers have repeatedly noted that 640,000 tonnes of fishing gear is lost annually—roughly twice the weight of the Empire State Building. Scientists now believe this number is unsubstantiated. To clarify the facts, researchers from the University of Tasmania in Australia surveyed fishers from seven countries about their use of five different gear types: gill nets, purse seines, trawl nets, longlines, and pots and traps. From the surveys, the scientists calculated annual gear loss rates for each fishing method and extrapolated that to fishing efforts around the world. The researchers estimate that fishing vessels lose around two percent of their gear every year, a staggering amount when taken together…

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

More on Pollution (Plastic, Hydrocarbon, Waste Water + Trash)

How to create a ‘world without waste’? Here are the plastic industry’s ideas – Grist Magazine

A deep dive into the petrochemical industry’s proposals for the global plastics treaty….

A new report looks at major companies’ efforts to address plastic waste — and finds them lacking – Grist Magazine

Of the 147 companies with a package recyclability goal, only 15 percent were on track to meet it…

How the recycling symbol lost its meaning – Grist Magazine

Of the 147 companies with a package recyclability goal, only 15 percent were on track to meet it…

The Plastics We Breathe | Interactive – the Washington Post

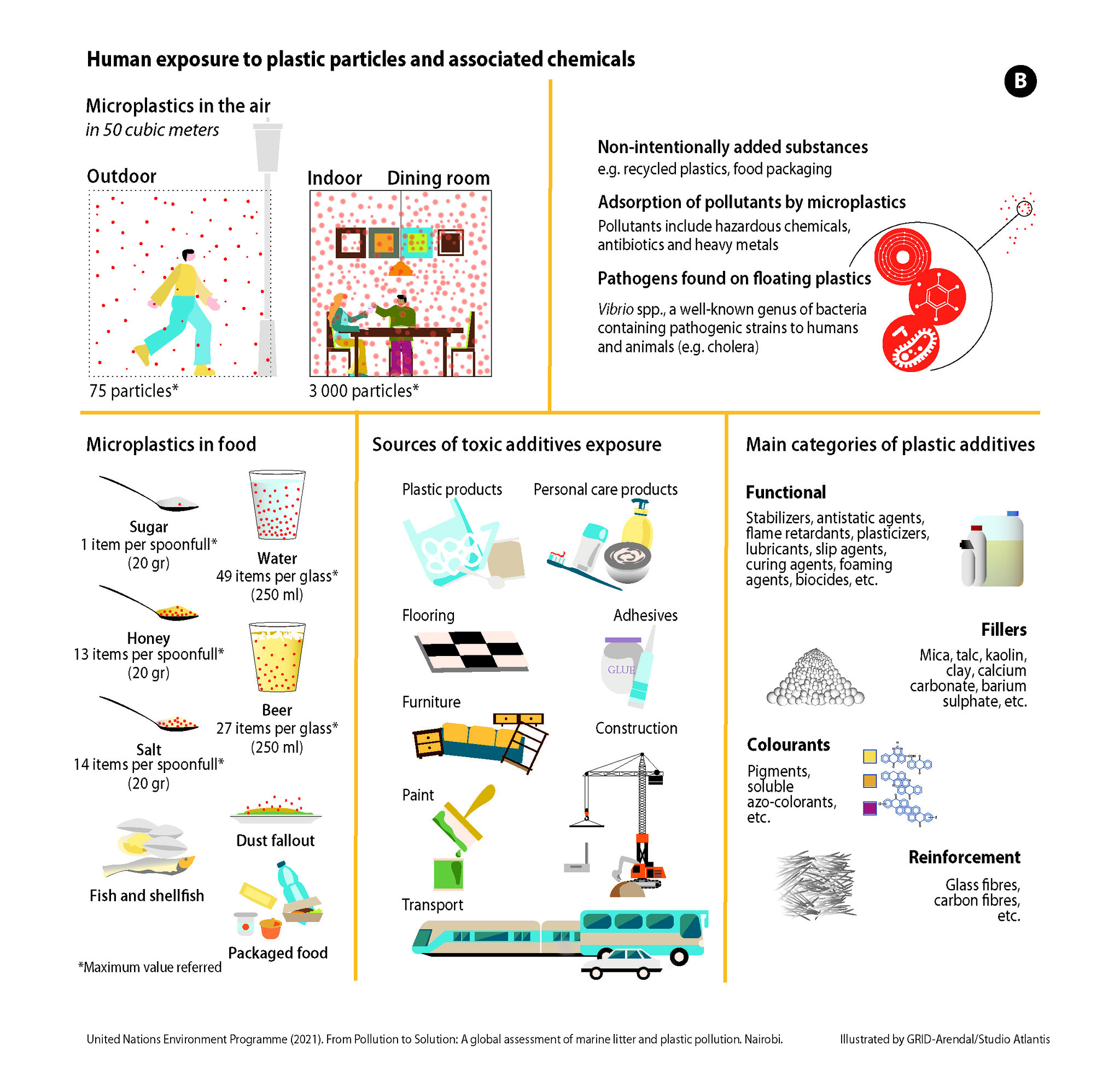

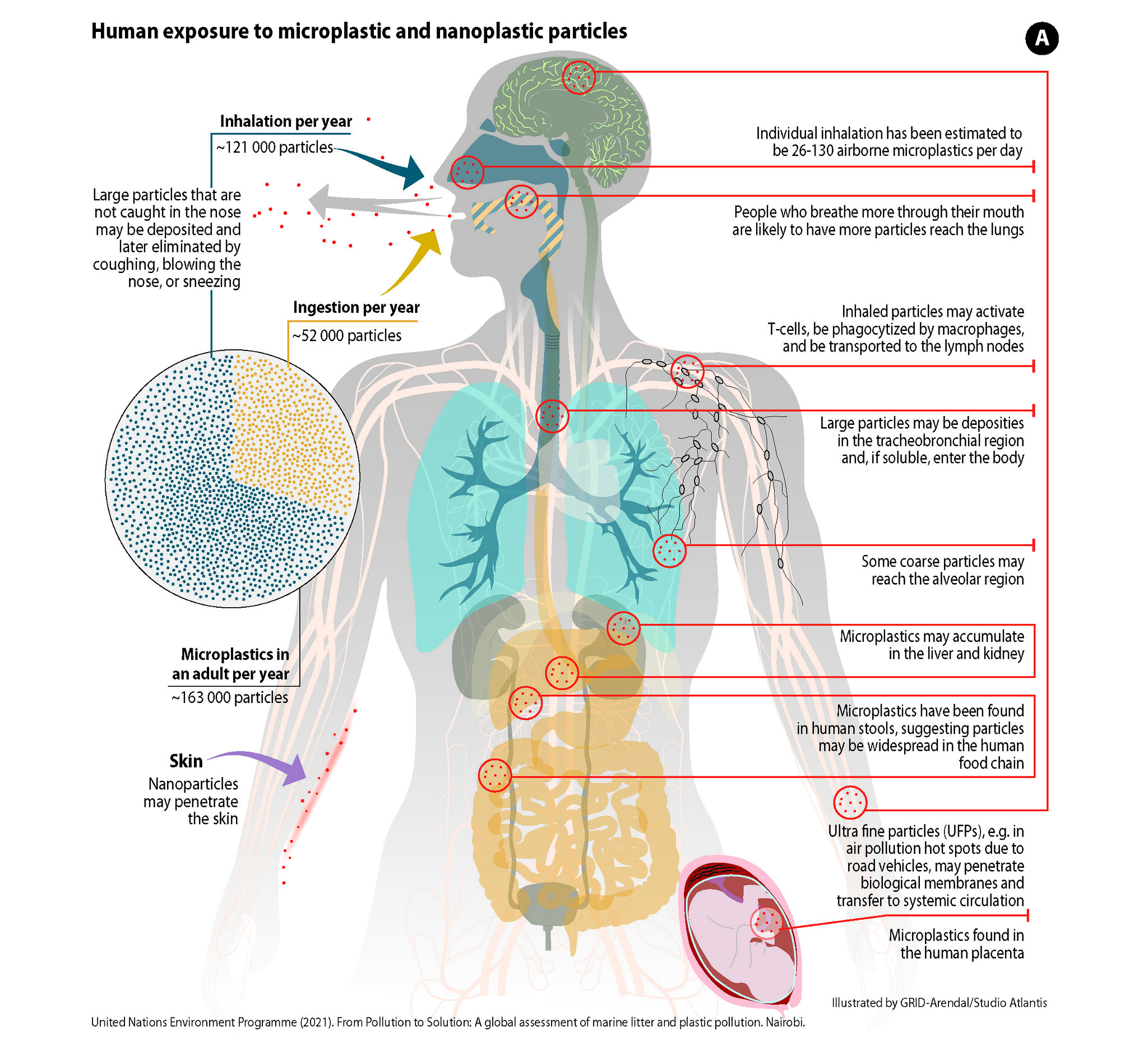

Every time you take a breath, you could be inhaling microplastics. Scroll to see how tiny and dangerously invasive they can be….

Can the circular economy help the Caribbean win its war against waste? – Mongabay

For decades, a graveyard of corroding barrels has littered the seafloor just off the coast of Los Angeles. It was out of sight, out of mind — a not-so-secret secret that haunted the marine environment until a team of researchers came across them with an advanced underwater camera…Startling amounts of DDT near the barrels pointed to a little-known history of toxic pollution…but federal regulators recently determined that the manufacturer had not bothered with barrels. (Its acid waste was poured straight into the ocean instead.)…

Giant Heaps of Plastic Are Helping Vegetables Grow – Atlantic Magazine

Plastic allows farmers to use less water and fertilizer. But at the end of each season, they’re left with a pile of waste…

Microplastics are in human testicles. It’s still not clear how they got there – Grist Magazine

People eat, drink, and breathe in tiny pieces of plastics — but what they do inside the body is still unknown…

‘I swam in the polluted Channel and now I need hearing aids’ – the Times UK

Maggie Alderson blames poor water quality off Hastings for an infection that punctured her ear drum. Samples taken from the sea would appear to back that up…

The more plastic companies make, the more they pollute – Grist Magazine

A new study, drawing on five years of data collected across 84 countries, proves what seems self-evident…