Coastal Management | Adaptation | Policy

May 31, 2024

Louisiana’s coast is sinking. Advocates say the governor is undermining efforts to save it – the Washington Times

Excerpt:

A new Republican governor is taking aim at the state’s coastal protection agency.

For the past decade, Louisiana’s program for coastal protection has been hailed as one of the best in the country, after the devastation from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita pushed the state to shore up coastlines, repair levees and protect natural habitats.

“The very future of our state is at stake,” the letter read.

Environmentalists say that the new governor’s actions could hobble the agency just as its work is most needed. The moves come as other right-leaning states are also cutting back on climate goals and even references to climate change. This month, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) signed a bill erasing most mentions of climate change from state law. DeSantis is also poised to nullify the state’s targets for 100 percent renewable energy by 2050.

Since 2005, when Louisiana was devastated by two hurricanes, the coastal restoration agency has built or revamped over 300 miles of levees that hold back floodwaters, and restored dozens of miles of barrier islands that can absorb the pressure of waves and rising seas. The agency works to shore up these defenses in the face of future, stronger storms and higher seas.

Its work is critical, experts say: Louisiana is losing coastline at a dramatic rate. In the past century, the state has lost over 2,000 square miles of land; it could lose 2,000 more in the next 50 years, scientists predict. As sea level rise has accelerated, so has the loss of land. Wetlands are “drowning” in many areas of the state — covered by sea level rise faster than they can grow. In the coming decades, scientists say, the state could lose up to 75 percent of its natural buffer against hurricanes and storms…

More on Coastal Management + Adaptation . . .

DeSantis signs bill scrubbing ‘climate change’ from Florida law – the Washington Times

Climate advocates said the bill is a bid for national attention from a Republican governor eager to use global warming as a culture war issue..

U.S. East Coast adopts ‘living shorelines’ approach to keep rising seas at bay – Mongabay

Excerpt: Along the U.S. East Coast, communities are grappling with the dual destructive forces of rising sea levels and stronger storms pushed by climate change,

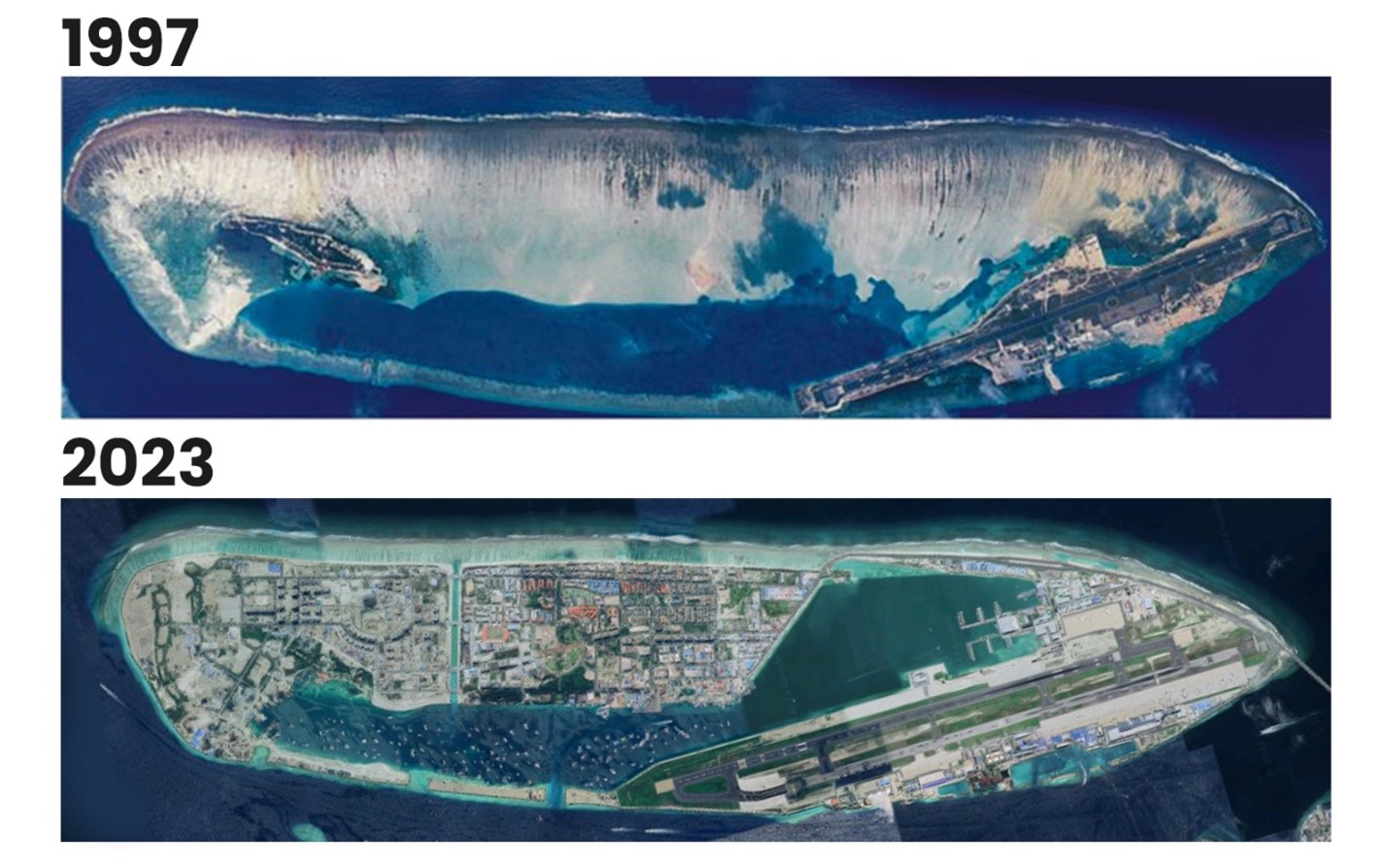

The Maldives Is Racing To Create New Land. Why Are So Many People Concerned? – Nature

Sun, sand and sea.” Those are the three ingredients for tourism in the Maldives, Mohamed Shaiz’s father told him. For more than a decade, Shaiz’s family owned a successful local hotel in Addu, the Maldives’ southernmost atoll. But nearly 9 months ago, the government took away the sea…

Behind the Story: Land Reclamation in the Maldives – the Pulitzer Center

Most visitors come to the Maldives for its resorts and pristine beaches. For Pulitzer Center grantee Jesse Chase-Lubitz, there’s a story behind that sand…The Maldives face an existential threat from sea level rise, and rebuilding the coastline with dredged sand has become a popular solution. But a series of activists on the 1,200-island archipelago are questioning the tradeoffs…Through interviews with taxi drivers, hotel owners, politicians, and scientists, Chase-Lubitz found that land reclamation is not a one-size-fits-all policy…

How Saving The Maldives May Actually Destroy It – the Medium

Just imagine waking up one day to find the sea that was once at your doorstep replaced by a fake 130-meter beach. This is the new reality for the residents of Addu, the southernmost atoll of the Maldives. But this shocking transformation isn’t new — it’s a desperate move to keep the country above water and thriving…

Maldives to battle rising seas by building fortress islands – PHYS.ORG

Rising sea levels threaten to swamp the Maldives and the Indian Ocean archipelago is already out of drinking water, but the new president says he has scrapped plans to relocate citizens. Instead, President Mohamed Muizzu promises the low-lying nation will beat back the waves through ambitious land reclamation and building islands higher—policies, however, that environmental and rights groups warn could even exacerbate flooding risks…