Plastic Pollution

“The unprecedented plastic waste tide plaguing our oceans and shores, can become as limited as our chosen relationship with plastics, which involves a dramatic behavioral change on our part…” — Claire Le Guern

March 19, 2025

How to eat and drink fewer microplastics – the Washington Post

Excerpt:

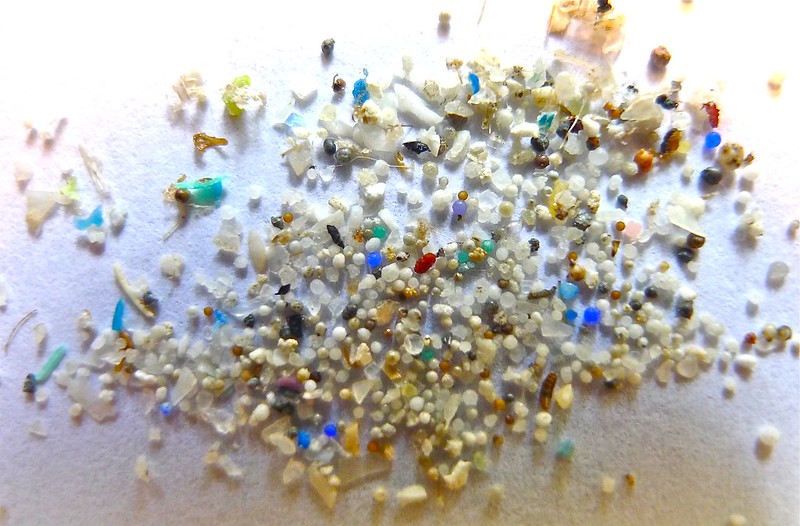

Scientists are finding microplastics throughout the human body. Here are some simple strategies to limit your exposure.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

More on Plastic Pollution . . .

Study finds microplastic contamination in 99% of seafood samples – the Guardian

The peer-reviewed study detected microplastics in 180 of 182 samples comprising five types of fish and pink shrimp…

In a first, scientists find microplastics are building up deep in our brains – the Washington Post

A new study shows that microplastics have crossed the blood-brain barrier — and that their numbers are rising…

Plastic pollution wipes out Kabul river’s turtles and Sher Mahi fish – the Express Tribune

Once a thriving haven for aquatic life, the Kabul River is now a shadow of its former self. Severe plastic pollution is poisoning the water and decimating the river’s biodiversity, including the famous Sher Mahi fish…

What’s the deal with microplastics, the material that ‘never goes away’? – SCOPE – Stanford Medicine

They’re in the water we drink, the food we eat, the clothes we wear and the air we breathe. They’ve pervaded every ecosystem in the world, from coral reefs to Antarctic ice. And they’ve infiltrated the human body, lodging themselves in everything from brain tissue to reproductive organs…

From paradise to plastics pollution: Bali’s battle for marine plastics debris – 360info

Bali has a unique opportunity to address plastic waste by integrating sustainable practices into the tourism experience.

Five firms in plastic pollution alliance ‘made 1,000 times more plastic than they cleaned up – the Guardian

Five oil and chemical companies which promised to divert plastic from environment produced 132m tonnes of it, analysis finds…

These countries produce the most plastic pollution in our oceans – and they’re not the ones you might have guessed – the Independent

Trillions of pieces of plastic are estimated to float in oceans around the world…

Chemist Identifies Mystery ‘Blobs’ Washing Up in Newfoundland – the New York Times

A researcher thinks he knows what has been coming ashore on miles of beaches. Canada’s environmental agency says it is still looking into it…

Plastic pollution is changing entire Earth system, scientists find – the Guardian

Pollution is affecting the climate, biodiversity, ecosystems, ocean acidification and human health, according to analysis..