The Santa Aguila Foundation has launched SandKids.org, a website focused on coastal issues specifically designed for younger audiences.

Through character driven and engaging storytelling, this newly launched site seeks to reinforce the natural curiosity and awe that all children have about their physical world, to impart knowledge and wonder, while also inspiring and empowering them act in environmentally conscious ways.

Children will join the SandKids: Sunny, Aguila, Lily, Skylar and Poppy, on coastal adventures full of discovery. The first episode of Sand Tales, “From the Mountain to the Sea” is available to view now.

Additional episodes will follow, and the plan is to create an online library of multilingual and audio-accessible resources that foster a love and connection to the coast that promotes a healthy sense of belonging and encourages sustainable practices and conservation efforts.

“In the end we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught…”

– Baba Dioum, 1968

SandKids.org (03-29-2025)

Sand Tales Episode 1: From the Mountains to the Sea

Welcome to a fantastic universe filled with exciting environmental science stories! Get ready to connect with nature, discover your hidden talents, and learn how to make a real difference.

Story by: Gilberto Cunha Junior

Science Consultant: Gary Griggs

Narrator: Deepika Shrestha Ross

Art Director and Illustrator: Gilberto Cunha Junior

Animators: Ana Von Randow, Katerine Franco (Daza), Gilberto Cunha Junior

Art Consultant: Herick Lemos

Stock Music and Sound Courtesy of: pixabay.com

Executive Producers & Sandkids.org Founders: Eva and Olaf

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Beaches | Coasts of the Month . . .

Photos of the Month . . .

CURRENT NEWS + RECENT POSTS

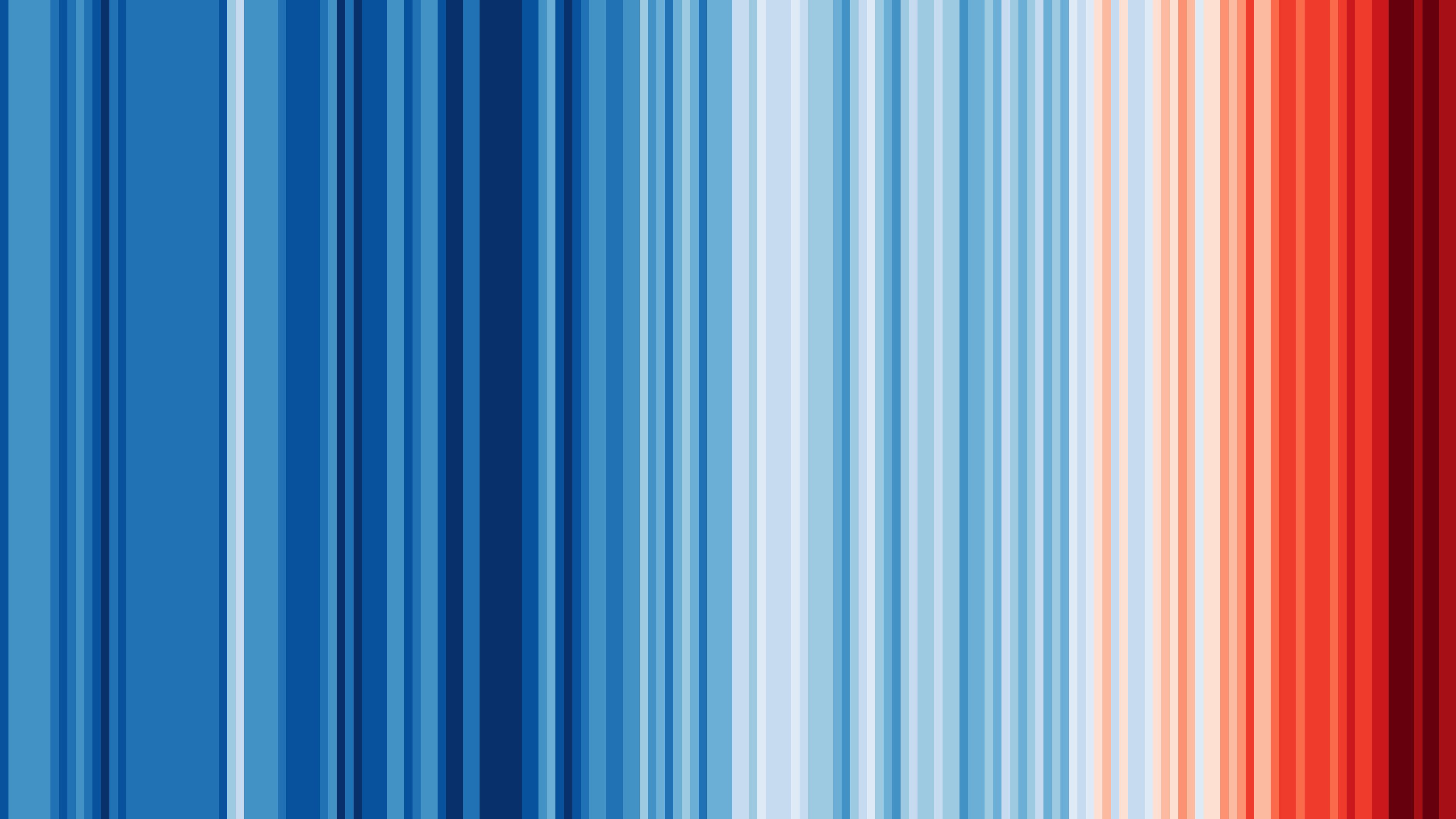

How Do We Identify Climate Change? – WWF Wild Classroom