Dams, Sand Supply Reduction + Habitat Recovery

July 1, 2024

When dams come down, what happens to the ocean? – High Country News | Hakai Magazine

Excerpt:

In Washington State, scientists studying the Elwha River Delta in the decade since the dam came down have revealed lasting changes—and a healthier ecosystem.

In late August 2024, Steve Rubin, a fish biologist with the US Geological Survey, will dive into the frigid, briny water of the Juan de Fuca Strait, nearly two kilometers from the mouth of the Elwha River in Washington State. It will be Rubin’s 12th dive at the site since the Elwha Dam was breached in 2011, sending a century’s worth of accumulated sediment surging downstream.

The megatonnes of sediment that were released by the dam’s removal were expected to help rebuild the twists and turns of the Elwha River. But some feared that they might end up suffocating the coastal ecosystems near the delta.

During Rubin’s first postremoval dive, he documented kelp, algae, invertebrates, and fish. The changes he saw were striking: Where there had been dense kelp forests, there was now bare ocean floor. The water was opaque with suspended sediment. At some dive sites near the delta, he could hardly see his outstretched hand. “It’s hard to describe. In some of our sites, there was nothing—literally zero individuals of some of these kelp and algae species,” Rubin says.

The kelp density near the river mouth decreased 77 percent in just a year, a worrisome development that the Seattle Times described as a “kelp Armageddon.” The removal of the Glines Canyon Dam, about 13 kilometers upriver of the Elwha River and 23 kilometers from the delta, started in 2013, releasing even more sediment. Kelp continued to decline that year—decreasing by 95 percent since before dam removal.

That wasn’t the whole story, though. When Rubin returned in 2015, he saw that, at many of his survey sites, the kelp had started to rebound. In 2018, studies revealed that the density of kelp in these sites resembled preremoval levels. Researchers believe the initial die-off was due to suspended sediment blotting out much of the sunlight, which kelp needs to grow. Once that sediment settled or washed away, the kelp recovered.

More than a decade after the Elwha Dam’s removal, researchers are finally getting a more full picture of its impact on coastal ecosystems. When the dams were breached, the coastline near the river’s mouth was completely remodeled. The sediment built stretches of sandy beaches and a series of swirling sandbars that peek above the water’s surface. These beaches and bars have allowed water to pool, forming a series of brackish lagoons. Plants and animals quickly colonized the new ecosystem. “It was like seeing a geologic event in a human time frame,” says Anne Shaffer, executive director and lead scientist of the Coastal Watershed Institute and affiliate professor at Western Washington University…

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

More on Dams and Sand Supply Reduction + Habitat Recovery

California will help return tribal lands as part of the historic Klamath River restoration – the Los Angeles Times

More than a century has passed since members of the Shasta Indian Nation saw the last piece of their ancestral home — a landscape along the Klamath River where villages once stood — flooded by a massive hydroelectric project.

Now more than 2,800 acres of land that encompassed the settlement, known as Kikacéki, will be returned to the tribe. The reclamation is part of the largest river restoration effort in U.S. history, the removal of four dams and reservoirs that had cut off the tribe from the spiritual center of their world…

Dammed but Not Doomed – Hakai Magazine

As dams come down on the Skutik River, the once-demonized alewife—a fish beloved by the Passamaquoddy—gets a second chance at life…

No turning back: The largest dam removal in U.S. history begins – NPR

The largest dam removal in U.S. history entered a critical phase this week, with the lowering of dammed reservoirs on the Klamath River…

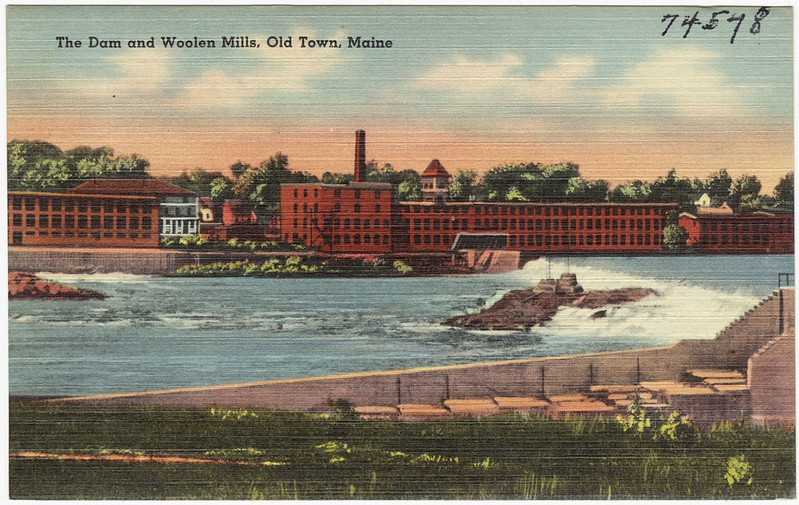

‘Take It Down and They’ll Return’: The Stunning Revival of the Penobscot River – reasons to be cheerful

A historic project in Maine shows that when dams are removed, a river and its fish can recover with surprising speed…

China’s Mekong dams turn Thai fishing villages into ‘ghost towns’- Context

From February to April each year, Kam Thon spends most of her days knee-deep in the waters of the Mekong River by her village in northern Thailand, gathering river weed to sell and cook at home. Kam Thon and other women who live by the Mekong have been collecting river weed, or khai, for decades, but their harvest has fallen since China built nearly a dozen dams upstream. The dams have altered the flow of water and block much of the sediment that is vital for khai and rice cultivation, researchers say…

Why are Tunisia’s beaches disappearing and what does it mean for the country? – Reuters

Rising sea levels are causing Tunisia’s beaches to gradually disappear. This is making life hard for the country’s tourism and fishing industries.

The Maghreb – made up of Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Libya – is more affected by coastal erosion than any region outside South Asia, the World Bank found in a 2021 study. Among these countries, Tunisia has had the highest erosion rates in the last three decades, averaging almost 70cm a year, it found…

Grains of Sand: Too Much and Never Enough – EOS Magazine

Sand is a foundational element of our cities, our homes, our landscapes and seascapes. How we will interact with the material in the future, however, is less certain…

“The use of sand is now faced with two major challenges,” said Xiaoyang Zhong, a doctoral student in environmental science at Leiden University in the Netherlands. “One is that it has caused enormous consequences in the environment,” he explained. “The second challenge is that easily usable sand resources are running out in many regions…”

Starving the Mekong – Reuters

Lives are remade as dams built by China upstream deprive the Mekong River Delta of precious sediment

Standing on the bank of the Mekong River, Tran Van Cung can see his rice farm wash away before his very eyes. The paddy’s edge is crumbling into the delta.

Just 15 years ago, Southeast Asia’s longest river carried some 143 million tonnes of sediment – as heavy as about 430 Empire State Buildings – through to the Mekong River Delta every year, dumping nutrients along riverbanks essential to keeping tens of thousands of farms like Cung’s intact and productive…

Florida beaches were already running low on sand. Then Ian and Nicole hit – the Washington Post

“I think we’re starting to discover that, despite our best efforts and wanting to throw as much money at this as possible, it has become very difficult to keep these beaches as wide as we would like to keep them,” Robert S. Young, a geology professor at Western Carolina University and director of the Program for Developed Shorelines… “We simply don’t have the capacity to hold all of these beaches in place.”