Excerpt:

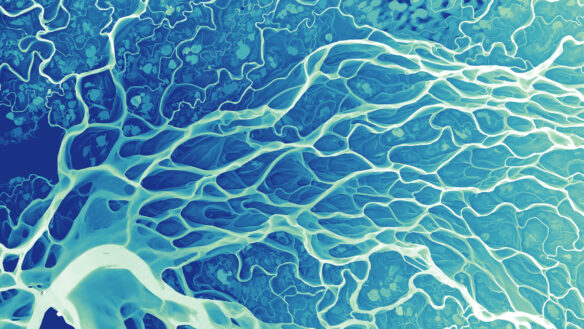

A historic project in Maine shows that when dams are removed, a river and its fish can recover with surprising speed.

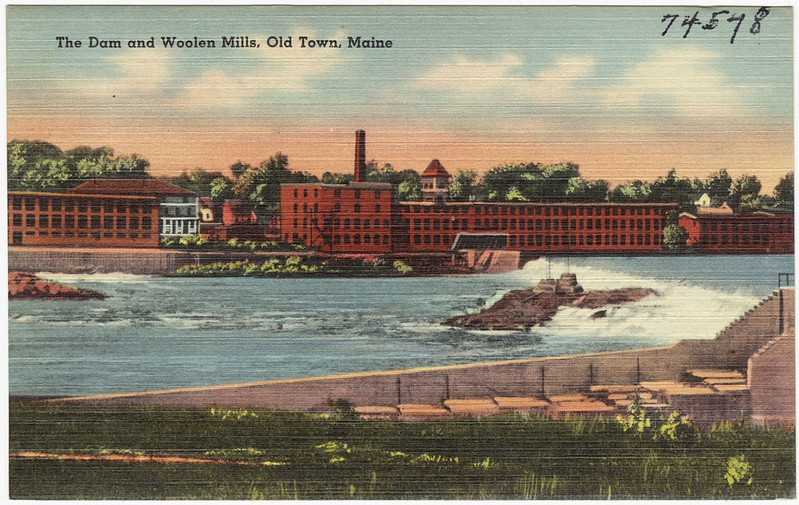

About a week before the removal of the Great Works Dam on the Penobscot River in Old Town, Maine, Dan Kusnierz dragged his sons to the riverside to take their picture in front of the aging structure. They had just come from a little league game. “They were being goofy and didn’t understand it,” Kusnierz, the water resources program manager for the Penobscot Indian Nation, recalls. It was 2012, and with the dam’s removal imminent, the river — New England’s second-largest — was about to transform.

For nearly two centuries, the Penobscot had been choked with logs and pulp as the timber and paper industries — both long-standing cornerstones of Maine’s economy — used it both as a lumber byway and waste receptacle. From just 1830 to 1880, more than eight billion feet of timber floated down the river. To power all this industry, dams were erected, 119 in the Penobscot River Basin alone. Two in particular, the Great Works and the Veazie, posed an outsized threat to the river’s health.

Perhaps irrelevant to his children posing for a picture at the time, Kusnierz, who is not Penobscot but has served the Nation for 20 years, was one the members of an unprecedented coalition of scientists, Indigenous people and conservationists working to remove both dams in order to free the Penobscot River and hopefully restore its health in the process.

The river had been sick for generations. Butch Phillips, a Penobscot Nation elder, recalls growing up on Indian Island, the Penobscot tribe reservation located near Old Town on the river, in the 1950s. By that time, the Penobscot was unrecognizable to the body of water it had once been, with drifting logs so gridlocked at times on the eastern side of the island that the river was impassable for boats and people alike. This posed an ongoing dilemma for the Penobscot people who, prior to the construction of a bridge in 1950, used canoes to travel to and from the mainland.

Despite the discharge coming from the mills, the river was still central to the Penobscot Nation’s everyday life. “[The river] was our playground,” Phillips says. “We were either canoeing on it, fishing, swimming in it and in the wintertime we were skating on it.” But the relationship had been affected. Living so closely with a body of water like the Penobscot for so many generations, he explains, “you develop a river culture. We are river people, we’re canoe people. And when you take away that element, that river and the use of the river, then you take away the culture as well…”

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (08-07-2013):

Veazie Dam Breached!