Habitats | Ecosystem Disturbance

July 16, 2024

Shrimp farms threaten Mexico’s mangroves and the jaguars that inhabit them – Mongabay

Excerpt:

Western Mexico’s rapidly expanding shrimp farms, many of which are illegal, are contributing to the deforestation of the Pacific coast’s mangroves, an important habitat for jaguars.

Among the spindly saline roots of the mangrove trees that line western Mexico’s coast, the jaguar is the ecosystem’s apex predator. Yet despite being at the top of the food chain, its existence is threatened by the abundance of another, much smaller species: the whiteleg shrimp.

Aquaculture of whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei), or Pacific white shrimp, has boomed along Mexico’s Pacific coast in the last couple of decades, in the process clearing swaths of mangrove forests and jeopardizing crucial habitats for jaguars (Panthera onca) in the western states of Sinaloa, Sonora and Nayarit.,

“With shrimp farms in Mexico, you see the destruction of the jaguars’ habitat,” Alfredo Quarto, co-founder of Mangroves Action Project, a conservation NGO, tells Mongabay. “But also of fish, crabs and other animals and birds. It’s very important to have a highly biodiverse supportive habitat.”

Habitat loss and poaching have shrunk jaguars’ distribution across Mexico by 54%, with about 4,000 to 5,000 of the big cats left in the wild today. In Nayarit, a 2022 study of a nearly 6,300-hectare (15,500-acre) wildlife corridor considered important for jaguar conservation found mangrove coverage there decreased from 35% to 26%, while land used for agriculture and aquaculture rose from 38% to 50% over a 20-year period.

Amid the habitat loss, a small reserve in Nayarit offers a haven for jaguars. La Papalota was a 368-hectare (909-acre) farm that in 2008 became the first private area in Nayarit that was voluntarily dedicated for conservation under a federal government program. The reserve is covered in thick mangrove forests to the south, with a mosaic of tropical deciduous and secondary forests elsewhere…

Mangroves are legally protected in Mexico, but that hasn’t stopped people from clearing them to set up shrimp ponds. Authorities frequently fail to take action, conservationists told Mongabay.

“Every time we visit the study site, we see new farms, new houses, new roads, and those rates of change are difficult for the jaguar populations to resist,” [Victor Hugo] Luja [a conservation biologist and researcher] tells Mongabay. “If the trend continues without taking action, I believe that in the space of 10 years, we could no longer have jaguar populations in the mangroves in Nayarit…”

The west coast of Mexico is key for shrimp farming, yet according to Luja, more than 40% of the shrimp farms don’t comply with federal regulations. With 980 shrimp farms in Nayarit alone, that would make nearly 400 of them noncomplying.

“These farms are not sustainable,” Quarto says. “They destroy the very environment that supports them…”

Also of Interest:

Jaguars Versus Shrimp

Ivan Carrillo | Earth Journalism Network |18 April 2024

Amid the darkness of night, a scene unfolds in the La Papalota reserve on the Mexican Pacific coast in Nayarit state. A female jaguar and her cub are engaged in play, with no one to witness the spectacle. Only the almost imperceptible click of an automatically activated reflex camera interrupts the action.

The resulting image shows the animals frozen in time, the cub’s paw resting on its mother’s back. The beautiful portrait captured by the hidden lens of a camera trap may appear to be the product of sheer chance. But it is not.

The image results from the obsessive efforts of Victor Hugo Luja, a professor and researcher at the Autonomous University of Nayarit, who has documented the lives of jaguars in this protected area of just 368 hectares for almost fifteen years. It won first prize in the Mangrove Action Project’s 2020 photography contest.

“The image is the product of at least three years of trying,” says Luja. “I tried and tried for the image, visualized it in my mind before taking it, and it turned out much better.”

Beyond its artistic value, the snapshot is scientifically noteworthy. It is atypical in that it shows jaguars in a mangrove forest, the ecosystem forming an interface between the land and sea. Jaguars here have surprised scientists by finding space in the mangroves to move, hunt, and reproduce. However, a threat is silently advancing, preying on a habitat already under significant pressure: it may seem antithetical to nature, but that threat is shrimp…

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

More on Habitat | Ecosystem Disturbance

Tromelin Island’s Impressive Comeback – Hakai Magazine

One small island in the Indian Ocean shows how quickly seabird populations can recover after people eradicate invasive predators…

How Florida is Getting Back Its Pink | Interactive – the Washington Post

When Keith Ramos heard a small flock of American flamingos had landed last fall at the nature preserve he oversees off Florida’s Atlantic coast, he rushed to get a once-in-a-lifetime glimpse of the gangly pink birds in the wild…

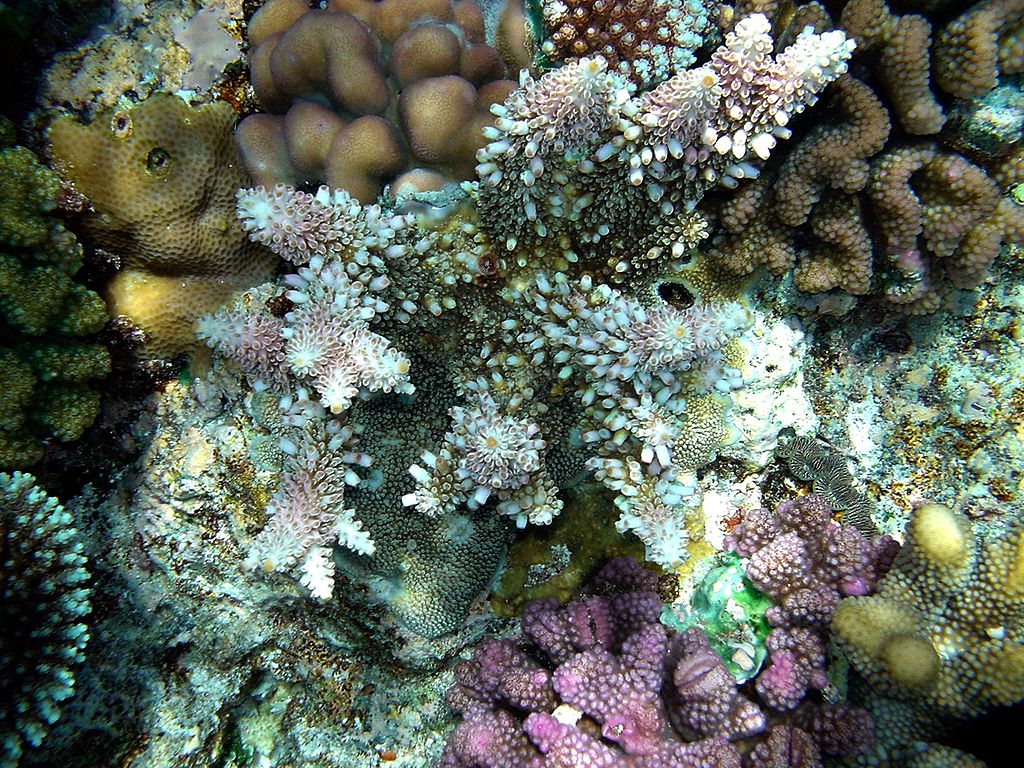

Seabird poop is recipe for coral recovery amid climate-driven bleaching – Mongabay

Researchers have found that nutrients from seabird poop led to a doubling of coral growth rates and faster recovery after bleaching events, promoting overall resilience…

A Healthy Coral Reef Is a Symphony – Reasons to be Cheerful Magazine

In the growing field of “ecoacoustics,” scientists use the ocean’s natural sounds to monitor the health of marine ecosystems — and even restore them…

The Gulf Coast is home to one of the last healthy coral reefs. It’s surrounded by oil – Grist Magazine

While the Gulf of Mexico is a region known for oil, it’s also home to something far less expected. Nestled among offshore oil platforms, about 150 miles from Houston, is one of the healthiest coral reefs in the world: the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary….

Naomi Longa wins 2024 Whitley Award for coral reef conservation in Coral Triangle – Oceanographic Magazine

Last night, the 2024 winners of the Whitley Awards were announced in London. Amongst other grassroot activists, Naomi Longa was given the prestigious award for her inspiring work with the Sea Women of Melanesia…

‘Like wildfires underwater’: Worst summer on record for Great Barrier Reef as coral die-off sweeps planet – CNN World

Rising sea temperatures around the planet have caused a bleaching event that is expected to be the most extensive on record…

Great Barrier Reef’s worst bleaching leaves giant coral graveyard: ‘It looks as if it has been carpet bombed’ – the Guardian

Last month the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority released a report warning that the reef was experiencing “the highest levels of thermal stress on record”. The authority’s chief scientist, Dr Roger Beeden, spoke of extensive and uniform bleaching across the southern reefs, which had dodged the worst of much of the previous four mass bleaching events to blight the Great Barrier Reef since 2016…

Corals are bleaching in every corner of the ocean, threatening its web of life – the Washington Post

First around Fiji, then the Florida Keys, then Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and now in the Indian Ocean. In the past year, anomalous ocean temperatures have left a trail of devastation for the world’s corals, bleaching entire reefs and threatening widespread coral mortality — and now, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and International Coral Reef Initiative say the world is experiencing its fourth global bleaching event, the second in the last decade…