Excerpt:

As dams come down on the Skutik River, the once-demonized alewife—a fish beloved by the Passamaquoddy—gets a second chance at life.

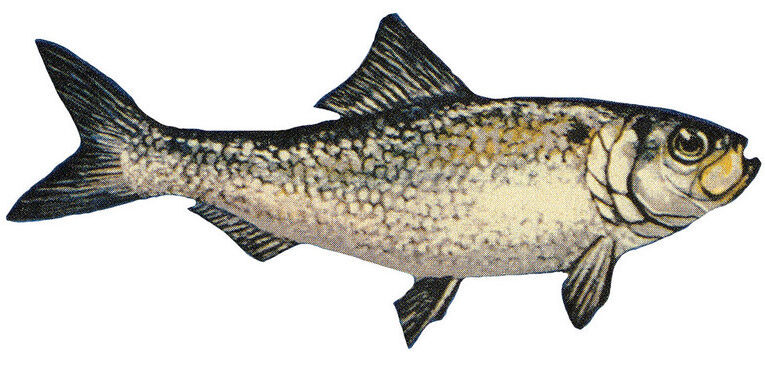

Heroic fish tales tend to focus on species with a certain je ne sais quoi: the leaping salmon, the globetrotting tuna, the mammoth marlin towering above its captor as it dangles from a scale. Not so much the modest alewife, flashing in the sunlight as a teenager stands on a riverbank in northern Maine and threatens to stuff it down the back of their friend’s shirt.

But on a mild day in mid-May, alewife—one of two closely related species referred to collectively as river herring—are the undeniable center of attention. On the banks of the Pennamaquan River, students from schools at the nearby Passamaquoddy Nation communities of Motahkomikuk (Indian Township) and Sipayik (Pleasant Point), Maine, gather in groups for Alewife Day. Some wade into the water downriver from a dam to scoop migrating alewives from the churning rapids with long-handled nets, while on the bank, other students, alternating between quiet concentration and enthusiastic retching, divide the fish into buckets so a visiting scientist can teach them how to collect biological information. As he shows the students how to scrape scales from the alewives’ bodies, the scientist apologizes for making them gag. “That’s okay, we signed up for this,” a student replies.

From a vantage point on the dam just upriver, Ralph Dana, with Sipayik’s environmental department, surveys the action. Dana, who often ends his sentences with an upward lilt, as if his enthusiasm is carrying his words skyward, says he likes coming here because it’s so similar to the much larger river at the heart of Passamaquoddy territory: the Skutik, or St. Croix, one river to the north. “It really is a scale model of our river,” he says. Like the Pennamaquan, the Skutik has dams; it has fishways, watery ramps that help fish swim around obstacles; and it has alewife, which, as Dana has spent the morning telling students, are in trouble.

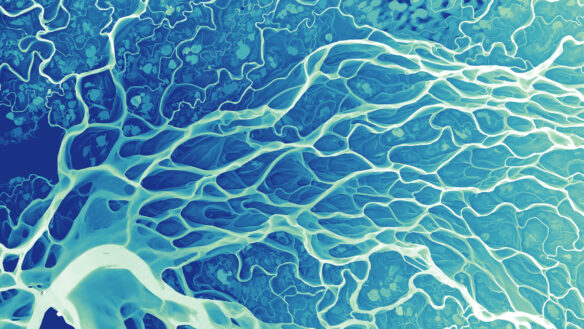

Every spring, runs of alewife (siqonomeq in Passamaquoddy)—a slender, shoebox-length fish suited to charging against the current—navigate from the Atlantic Ocean to the freshwater habitats where they spawn, traveling up rivers and streams across northeastern North America. The Skutik, which begins at a group of lakes puddled along the Maine–New Brunswick border and runs 185 kilometers along the international boundary to Passamaquoddy Bay, plays a particularly important role in this migration: the river once supported what was the largest run of alewife in Maine, and potentially on the continent, a coursing silver line connecting the fresh water and the sea, some 80-million-fish strong.

For the Passamaquoddy, a nation of approximately 3,500 people whose territory straddles the Canada–United States border, the abundance of alewife in the Skutik River supported a way of life stretching back millennia. (Archaeological work in the territory has found alewife bones in charcoal pits dating back 4,000 years.) But over centuries, the Passamaquoddy were forced off their territory, even as dams blocked the passage of alewife upstream. At one point, barriers threatened to wipe alewife out from the river altogether.

After years of effort led by the Passamaquoddy, alewife are now poised to recover. Last summer, work began on the most significant step yet: removal of the Milltown Dam, the first barrier fish encounter when migrating upstream. That work is expected to be completed in 2024.

Yet, the removal of this dam, which was built in the 1880s, is only one step in a much longer journey toward restoring alewife, and their habitat, across the Passamaquoddy Nation’s territory—a journey that has united scientists, Indigenous communities, and officials from occasionally squabbling countries on both sides of the border. Such a restoration would benefit the whole ecosystem—everything from whales to eagles to salmon eat alewives—as well as industries like lobster fishing, but it’s also inseparable from the nourishment of the communities surrounding it. And if there’s a fish who could carry this responsibility, it’s the unassuming alewife; to the Passamaquoddy, this fish feeds all…