Excerpt:

Atmospheric rivers can cause catastrophic flooding and landslides but are crucial for water supply. In an era of increasing weather whiplash between flood and drought, can we learn to embrace the rains?

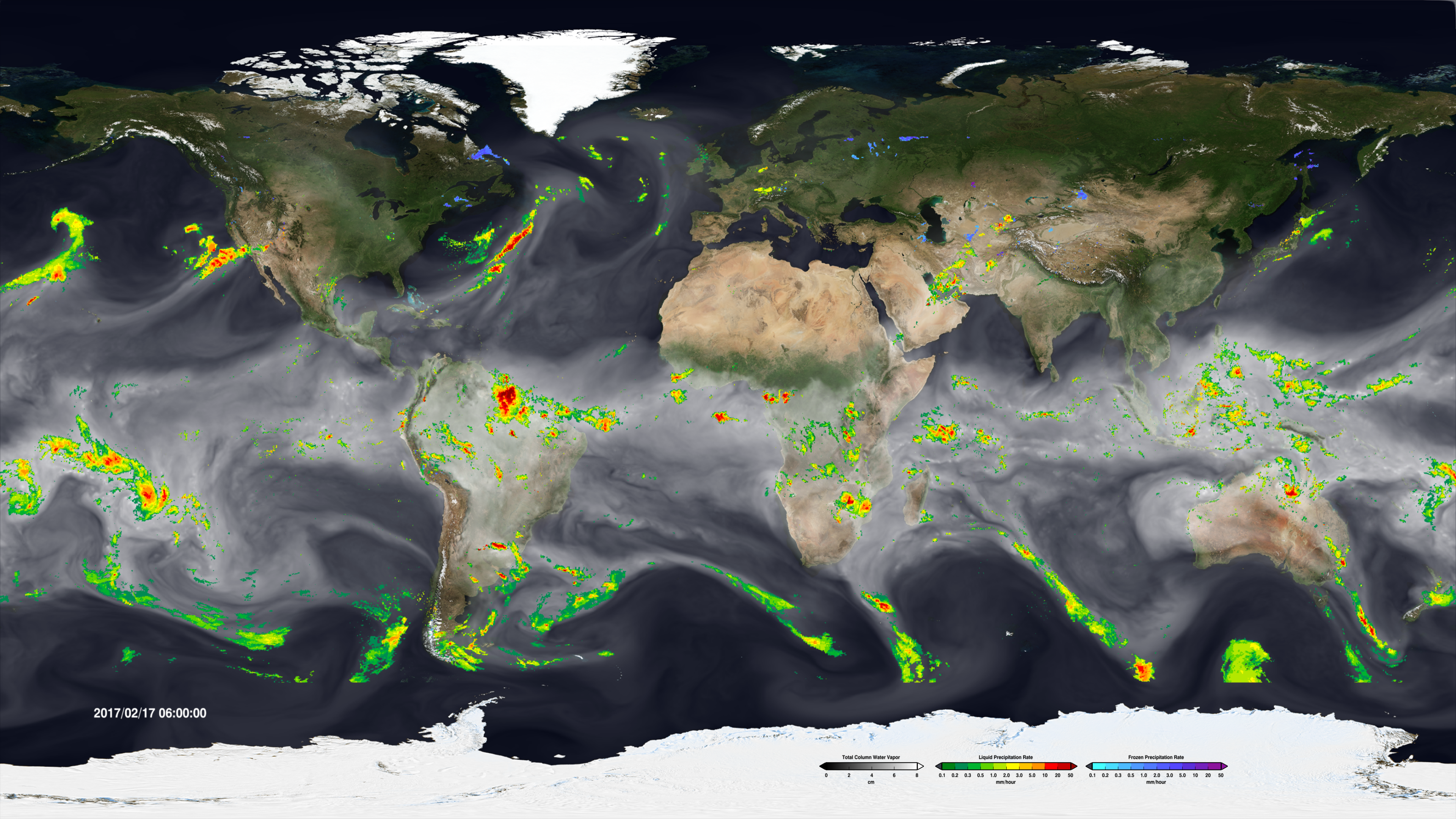

In mid-November 2021, a great storm begins brewing in the central Pacific Ocean north of Hawai‘i. Especially warm water, heated by the sun, steams off the sea surface and funnels into the sky.

A tendril of this floating moisture sweeps eastward across the ocean. It rides the winds for a day until it reaches the coasts of British Columbia and Washington State. There, the storm hits air turbulence, which pushes it into position—straight over British Columbia’s Fraser River valley.

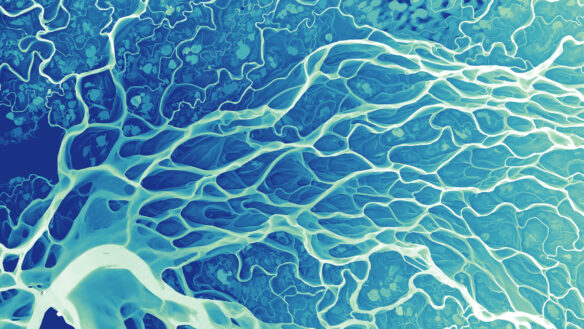

Clouds gather and darken. Below, a patchwork of farms and subdivisions sprawls along the Fraser River from its mouth, south of Vancouver, to the eastward mountain slopes, and southeast across the US border. At the center of the valley lies Abbotsford, a city of around 150,000 people nestled in a fingerprint-like depression between two mountains. As the stream of humid air rises toward the peaks, it cools, condenses, and bursts.

To Murray Ned, it sounds like a creek is overflowing outside his home in Kilgard, on a hillside within Abbotsford that’s part of the Semá:th (Sumas) First Nation reserve. Lying in bed, Ned listens to water overflow his rain gutters and splash two stories to the ground. Rain is common in Abbotsford in November, but it’s usually quiet. And it usually lets up.

Over the next two days, nearly a month’s worth of rain dumps here and in other parts of the province. The resulting floods and landslides kill at least six people, rip apart buildings, and buckle roads. In Abbotsford, more than 1,000 homes are swamped and 640,000 farm animals perish as rivers reclaim agricultural land in the floodplain.

But amid the losses, Ned sees something else. The Tuesday evening of the flood—after he has vacuumed water from his mother’s basement and moved the family’s horses to high ground—the deluge stops. Ned settles into a folding chair in his backyard, pulls out a Kokanee lager, and takes in the view. The flood laps knee-high against his horse barn. Semá:th Xó:tsa, Sumas Lake, has returned to the territory…