Excerpt:

“We need her conception of “histofuturism” now more than ever.

Somehow she knew this time would come. The smoke-choked air from fire gone wild, the cresting rivers and rising seas, the sweltering heat and receding lakes, the melting away of civil society and political stability, the light-year leaps in artificial intelligence—Octavia Butler foresaw them all.

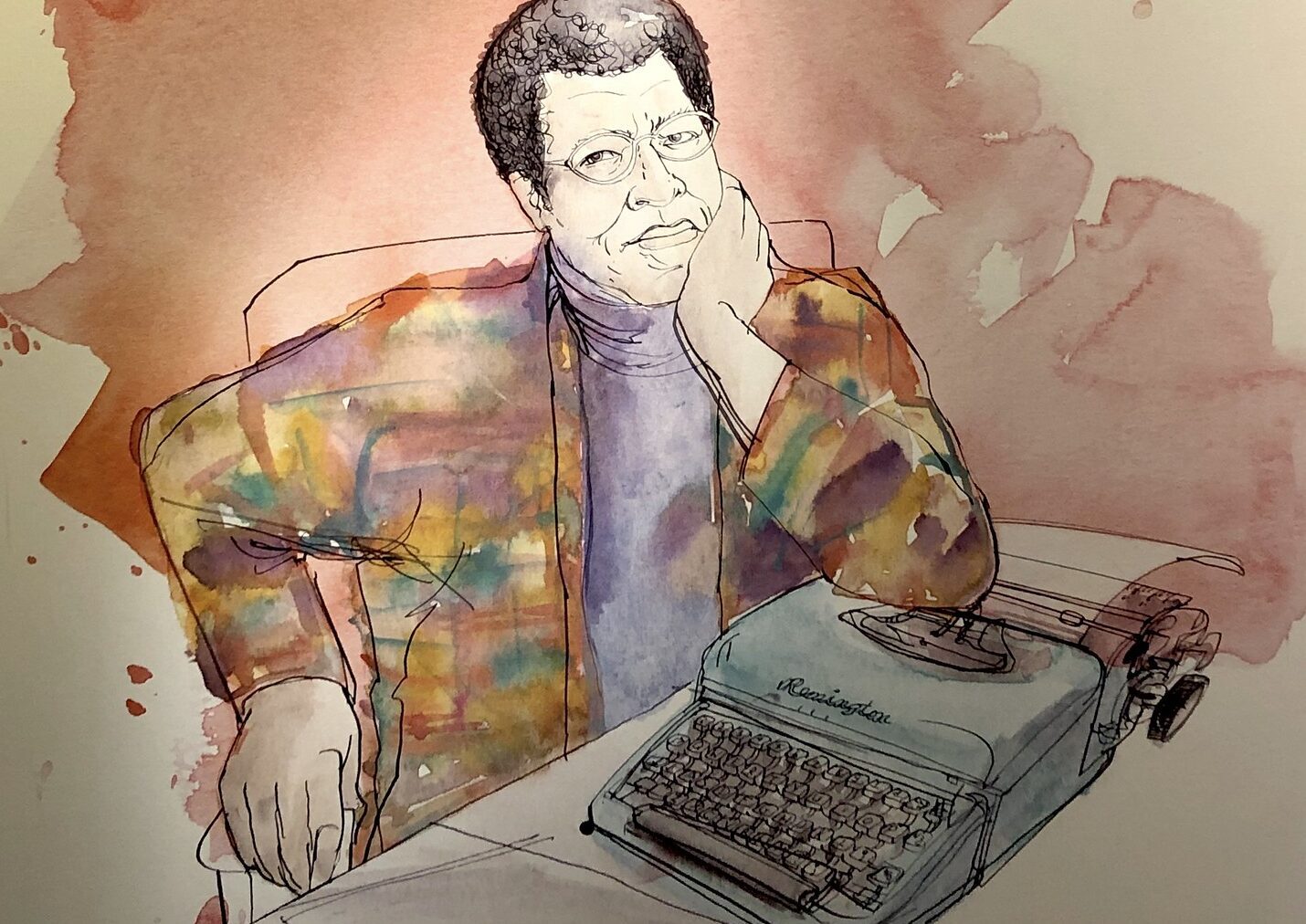

Butler was not a climate scientist, a political pundit, or a Silicon Valley technologist. The author of imaginative and often disturbing speculative fiction such as Parable of the Sower (1993), she was a Black woman descended from enslaved people in Louisiana, raised by a strictly religious mother in Los Angeles, educated at community and regional colleges, and besieged by feelings of professional marginalization for most of her too-short life. Out of these challenging circumstances (which included watching her grandparents’ chicken farm burn to the ground), and through the noise of late-20th-century America, Butler heard a clear signal: The future would not be like the present; it would, instead, be a techno-juiced doppelgänger of the past.

Butler’s vision fits our disorienting moment of flashbacks and fast-forwards. Russia’s corrupt designs on a reconstituted Soviet empire, devastating war in the Middle East, the resurgent appeal of white ethnonationalism—it’s as though 20th-century scenes are replaying before us, reconfigured for maximal 21st-century damage.

I am an academic historian, and for years I taught Butler’s historical fiction in my classes (particularly 1979’s Kindred, which follows a Black woman wrenched back in time to live with her enslaved ancestors). But I avoided her futuristic novels, which I found too harrowing to read.

When Parable came out, I was a graduate student working part-time in a collectively owned feminist bookshop in Minneapolis called Amazon Bookstore. (Even this detail smacks of the strangeness of past-future collisions—a few years later, that cozy shop would reluctantly relinquish its name to Amazon Books, which was not yet the behemoth we know as Amazon.com.) Our book club selected Parable, but I could not bear the violence and desolation of Butler’s fallen world. So I put the novel down and did not pick it up again for more than two decades. When I finally did, it was because of its resonance with a historical artifact I was studying—a cotton sack packed by an enslaved mother for her daughter right before they were separated by sale. The daughter used this sack as a lifeline. In Parable, the teenage protagonist packs a similar survival sack, which she uses to flee a deadly attack on her neighborhood. I was hooked. And I saw that it was this overlap between Butler’s two modes—past and future—that makes her canon so special…