A 1993 dystopian novel imagined the world in 2024. It’s eerily accurate – the Washington Post

Excerpt:

Octavia Butler’s ‘Parable of the Sower’ predicted devastating climate change, inequality, space travel and ‘Make America great again’

This is life in 2024.

Or at least it’s life in 2024 as imagined by the writer Octavia Butler 31 years ago.

“Parable of the Sower,” a 1993 novel by the late science fiction writer and MacArthur Fellow, depicts a future America ravaged by ecological collapse and civil unrest. The book’s narrator, African American teenager Lauren Olamina, begins writing a journal in July 2024 documenting the upheaval.

In the time it’s taken us to reach 2024 for real, Butler’s story has been adapted as an opera and a graphic novel; a movie adaptation is also in the works. In 2017, director Melina Matsoukas cited Butler among the Black thinkers who inspired her “Formation” video from Beyoncé’s award-winning album “Lemonade.”

In September 2020 — perhaps fueled by an interest in apocalyptic fiction prompted by covid-19 lockdowns — “Parable” appeared on the New York Times bestseller list for the first time, 27 years after publication.

Butler didn’t live to see the renewed interest in her ninth novel — she died in 2006 — but she indicated that the issues faced by the characters in “Parable” and by the United States today were inevitable…

ADDITIONAL READING . . .

How Octavia Butler Told the Future - the Atlantic

Excerpt:

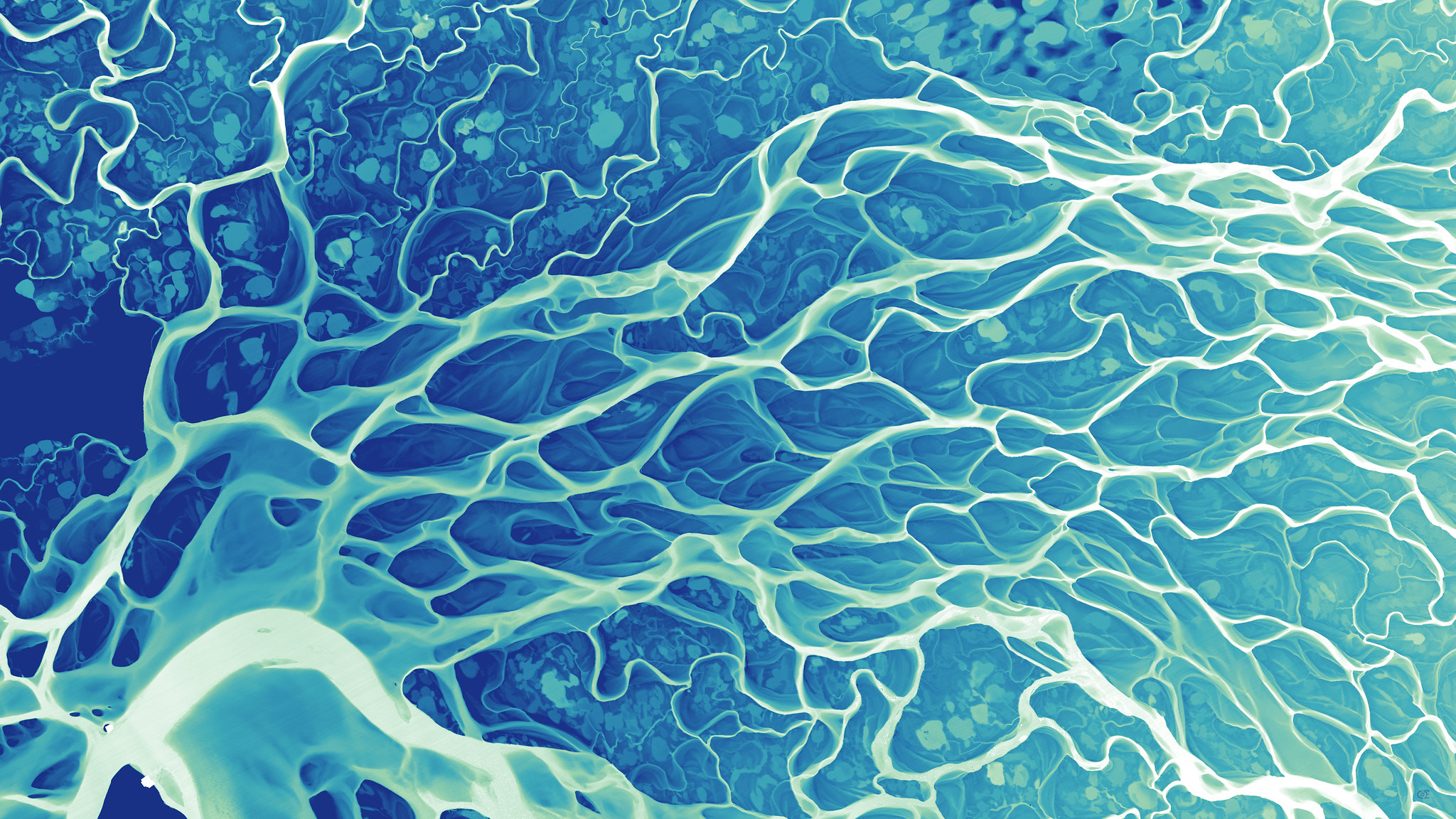

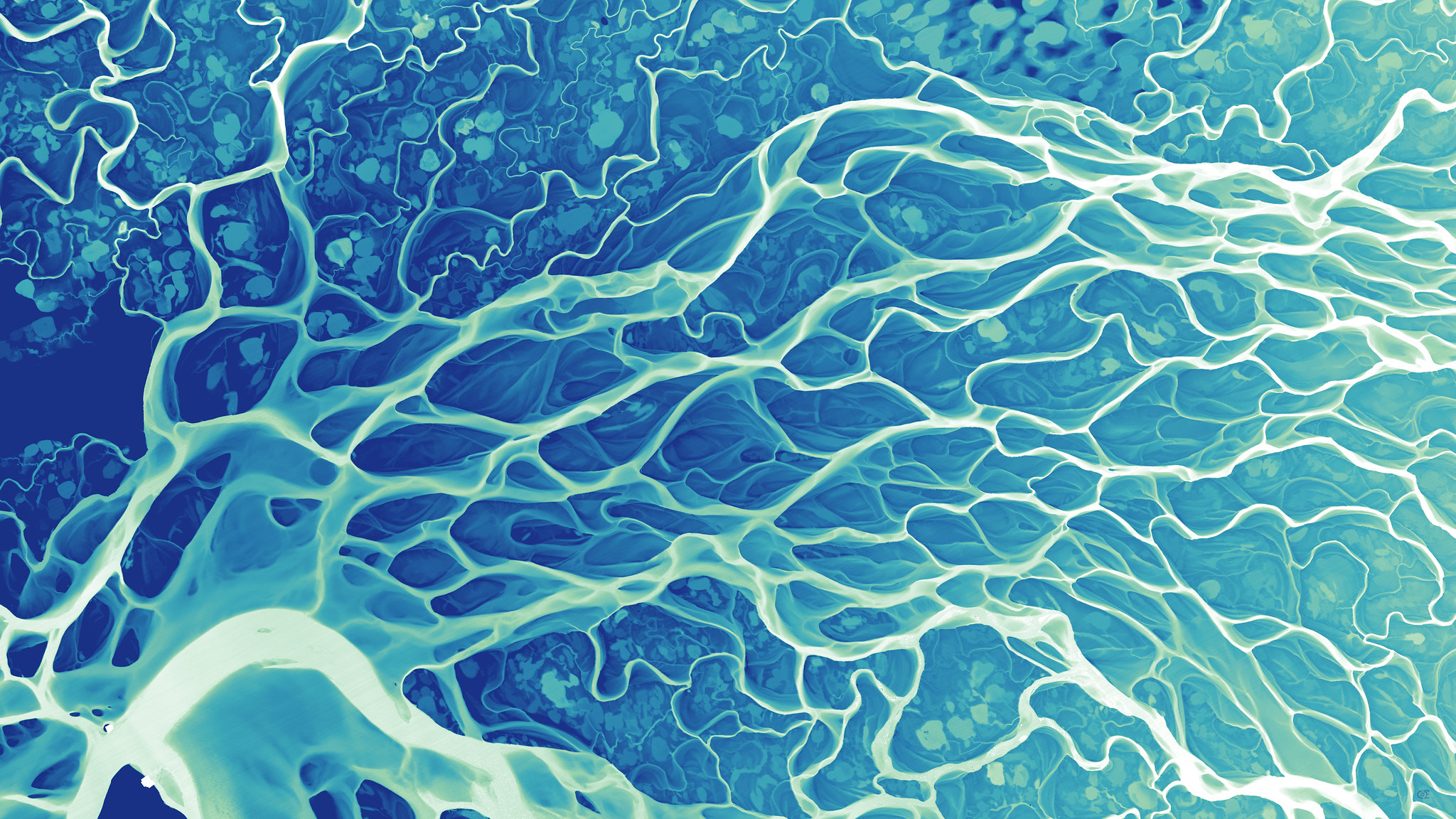

River histories visualized as entangled, intricate textures

Cartographer Daniel Coe uses relative elevation data, primarily from plane-mounted lasers called lidar, to visualize Earth’s natural features, like rivers and floodplains. His stunning river maps reveal stories hidden in historical sediment and past channels carved by the water, as it twists and turns through both landscape and time.

Also of Interest:

Jessica Stewart | My Modern Met (11-23-2023)

Artistic Views of the World’s Rivers and Deltas Created Using Lidar Data

Michael Crowe | High Country News (07-1-2022)

The beauty buried in the data

Excerpt:

Graphics editor Daniel Coe has always been captivated by maps, and his love of cartography has only grown over the years. For the past several years, he has been creatively using this passion to make stunning artwork focused on the world’s rivers. Coe takes advantage of open-source lidar data to put together evocative maps that tell the history of these rivers and deltas…

Excerpt:

Daniel Coe, the graphics editor for the Washington Geological Survey, creates surreal composite images showing rivers, ridges and other natural features from above…The process begins with survey teams gathering laser scans using LiDAR…Then Coe adds artificial light and color — sometimes even aerial photography — to the topographical renderings, exposing the beauty buried in the data…

The Visions of Octavia Butler | Interactive - the New York Times

Excerpt:

River histories visualized as entangled, intricate textures

Cartographer Daniel Coe uses relative elevation data, primarily from plane-mounted lasers called lidar, to visualize Earth’s natural features, like rivers and floodplains. His stunning river maps reveal stories hidden in historical sediment and past channels carved by the water, as it twists and turns through both landscape and time.

Also of Interest:

Jessica Stewart | My Modern Met (11-23-2023)

Artistic Views of the World’s Rivers and Deltas Created Using Lidar Data

Michael Crowe | High Country News (07-1-2022)

The beauty buried in the data

Excerpt:

Graphics editor Daniel Coe has always been captivated by maps, and his love of cartography has only grown over the years. For the past several years, he has been creatively using this passion to make stunning artwork focused on the world’s rivers. Coe takes advantage of open-source lidar data to put together evocative maps that tell the history of these rivers and deltas…

Excerpt:

Daniel Coe, the graphics editor for the Washington Geological Survey, creates surreal composite images showing rivers, ridges and other natural features from above…The process begins with survey teams gathering laser scans using LiDAR…Then Coe adds artificial light and color — sometimes even aerial photography — to the topographical renderings, exposing the beauty buried in the data…

ALSO OF INTEREST . . .

TED-Ed (02-25-2019):

Why should you read sci-fi superstar Octavia E. Butler?

Much science fiction features white male heroes who blast aliens or become saviors of brown people. Octavia E. Butler knew she could tell a better story. She built stunning worlds rife with diverse characters, and brought nuance and depth to the representation of their experiences…

Storied – PBS (06-29-2021):

Octavia Butler, The Grand Dame of Science Fiction | It’s Lit

If you are a fan of science fiction a name you should be familiar with is Octavia E. Butler. One of the most prolific and important Black authors in the genre, Butler’s storytelling pushed the boundaries of what Black people were allowed to be in science fiction…Hosted by Lindsay Ellis and Princess Weekes..

EXHIBITION:

Hyde Park Art Center (Exhibit runs from 11-11-2023 through 03-03-2024):

Candace Hunter: The Alien‐Nations and Sovereign States of Octavia E Butler

In The Alien‐Nations and Sovereign States of Octavia E Butler, Candace Hunter presents new works created with synthetic plants, remnants of a sustainable food experiment, a reading nook, and painted doors as imagined portals to other worlds to create what she describes as an “alien lush space.” The exhibition addresses the concepts of nationhood. Candace Hunter poses questions about who is other, and in what situations do we see people as other to ourselves? How do we become universal?