Venice Isn’t Alone: 7 Sinking Cities Around the World – How Stuff Works

Many big cities sit near the ocean. They became cities in the first place because their ports facilitated trade and travel by sea.

Coastal cities all over the world are sinking — a geological process called subsidence — and it’s happening at a rate that makes scientists nervous. If these bits of land didn’t have important cities on them, it’s likely nobody would notice, or, in some cases, that they wouldn’t be sinking at all…

Before the flood: how much longer will the Thames Barrier protect London? – the Guardian

The last time the Thames broke its banks and flooded central London was on 7 January 1928, when a storm sent record water levels up the tidal river, from Greenwich and Woolwich in the east as far as Hammersmith in the west. Built on flood plains, the capital was defended only by embankments. The flood waters burst over them into Whitehall and Westminster, and rushed through crowded slums. Fourteen died and thousands were left homeless…

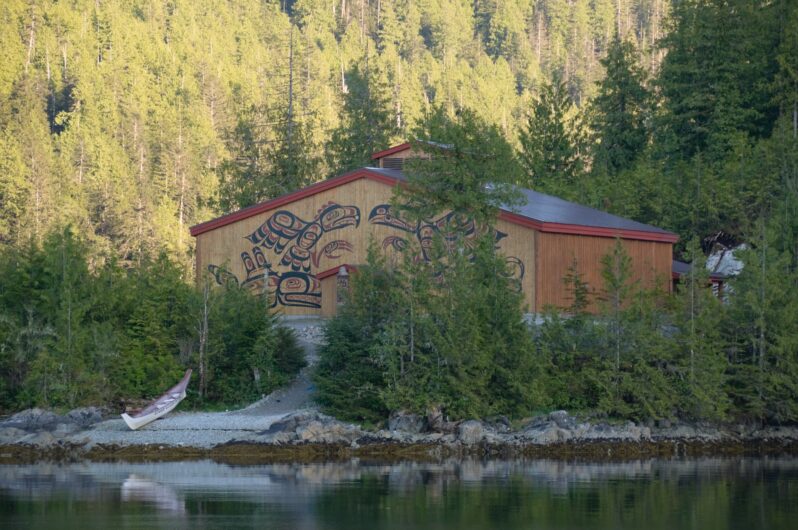

How First Nations Are Asserting Sovereignty Over Their Lands and Waters – the Tyee

Indigenous Marine Protected and Conserved Areas hold a key to food security and balancing ecological and economic priorities. Part one of two.

Kitasu Bay sits within the traditional territory of the Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nation and is located on the Central Coast of British Columbia. Last summer the nation declared it a protected area under their own laws, closing it to commercial harvest by non-Indigenous fishers. Their declaration invited the provincial and federal governments to work with them to develop a co-governance model, but added, “we seek no permission…”

At last, Venice’s authorities admit the risk from sea-level rise – The Art Newspaper

At a conference organised by the new Venice Sustainability Foundation in June, major public figures agreed for the first time that sea-level rise is the main problem facing the city now…

To restore coastal marine areas, we need to work across multiple habitats simultaneously – PNAS

Restoration of coastal marine habitats—often conducted under the umbrella of “nature-based solutions”—is one of the key actions underpinning global intergovernmental agreements, including the Paris Agreement and the 2021–2030 United Nations (UN) Decade of Restoration. To achieve global biodiversity and restoration targets…we need methods that accelerate and scale up restoration activities in size and impact. Part of the solution is cross-habitat facilitation—positive interactions that occur when processes generated in one habitat benefit another…

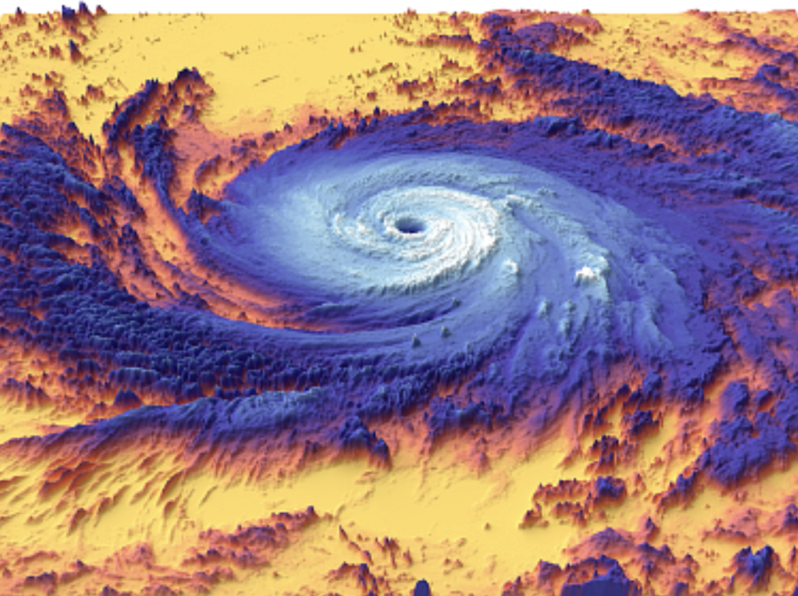

Hurricanes push heat deeper into the ocean than scientists realized, boosting long-term ocean warming, new research shows – the Conversation

Seven years ago an exceptionally strong El Niño took hold in the Pacific Ocean, triggering a cascade of damaging changes to the world’s weather. Indonesia was plunged into a deep drought that fueled exceptional wildfires, while heavy rains inundated villages and farmers’ fields in parts of the Horn of Africa. The event also helped make 2016 the planet’s hottest year on record. Now El Niño is back…

Is Fukushima wastewater release safe? What the science says – Nature

Despite concerns from several nations and international groups, Japan is pressing ahead with plans to release water contaminated by the 2011 meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean. Starting sometime this year and continuing for the next 30 years, Japan will slowly release treated water stored in tanks at the site into the ocean through a pipeline extending one kilometre from the coast. But just how safe is the water to the marine environment and humans across the Pacific region?

My art uses plastic recovered from beaches around the world to understand how our consumer society is transforming the ocean – the Conversation

“I am obsessed with plastic objects. I harvest them from the ocean for the stories they hold…Each object has the potential to be a message from the sea – a poem, a cipher, a metaphor, a warning. My work collecting and photographing ocean plastic and turning it into art began with an epiphany in 2005, on a far-flung beach at the southern tip of the Big Island of Hawaii…

Curious Kids: If plastic comes from oil and gas, which come originally from plants, why isn’t it biodegradable? – the Conversation

Question from Neerupama, age 11, Delhi, India..

To better understand why plastics don’t biodegrade, let’s start with how plastics are made and how biodegradation works…