Image Source: Mock, C.J., M. Chenoweth, I. Altamirano , M.D. Rodgers, and R. García-Herrera. The Great New Orleans Hurricane of 1812. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 91: 1653-1663.

Excerpt from the University of South Carolina

Nearly 200 years before Hurricane Katrina, a major storm hit the coast of Louisiana just west of New Orleans. Because the War of 1812 was simultaneously raging, the hurricane’s strength, direction and other historically significant details were quickly forgotten or never recorded.

But a University of South Carolina geographer has reconstructed the storm, using maritime records, and has uncovered new information about its intensity, how it was formed and the track it took.

Dr. Cary Mock’s account of the “Great Louisiana Hurricane of 1812” appears in the current issue of the Journal of the American Meteorological Society, a top journal for meteorological research.

“It was a lost event, dwarfed by history itself,” said Mock, an associate professor in the College of Arts and Sciences. “Louisiana was just in possession by the United States at the time, having been purchased from France only years before, and was isolated from the press.”

Mock says historians have long known that a hurricane hit New Orleans on Aug. 19, 1812, but they didn’t know the meteorological details about the storm.

“Hurricane Katrina is not the worst-case scenario for New Orleans, as its strongest winds were over water east of the eye,” said Mock. “The 1812 hurricane was the closest to the city, passing just to the west. It wasn’t as big as Katrina, but it was stronger at landfall, probably a mid-three or four category hurricane in terms of winds.”

Detailed information about past hurricanes is critical to helping climatologists today forecast and track hurricanes. But until recently, little was known of hurricanes that occurred before the late 19th century, when weather instrumentation and record keeping became more sophisticated and standardized. Mock’s research has shed light on much of the nation’s hurricane history that has remained hidden for centuries.

“A hurricane like the one in August 1812 would rank among the worst Louisiana hurricanes in dollar damage if it occurred today,” said Mock. “Hurricane Betsey was 100 miles to the west. Katrina was to the east. A 1915 hurricane came from the South. By knowing the track and intensity, as well as storm surge, of the August 1812 hurricane, we have another worst-case-scenario benchmark for hurricanes. If a hurricane like it happened today, and it could happen, it would mean absolute devastation.”

Mock has spent the last decade conducting research and creating a history of hurricanes and severe weather of the Eastern U.S. that dates back hundreds of years. Using newspapers, plantation records, diaries and ship logs, he has created a database that gives scientists the longitudinal data they’ve lacked. His research has been funded by nearly $700,000 in grants from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Mock began researching the August 1812 hurricane along with other early Louisiana hurricanes in 2006. It took 18 months for him to reconstruct the 1812 storm’s complete track.

Newspaper accounts, which included five from Louisiana and 17 from other states, described hourly timing of the storm’s impact, wind direction and intensity, rainfall, tide height and damage to trees and buildings.

The Orleans Gazette description of the impact of storm surge on the levees is one example:

“The levee almost entirely destroyed; the beach covered from fragments of vessels, merchandize, trunks, and here and there the eye falling on a mangled corpse. In short, what a few hours before was life and property, presented to the astonished spectator only death and ruin,” reported the newspaper.

The environmental conditions of the Louisiana coast were different in 1812; the sea level was lower, elevation of the city was higher and the expanse of the wetlands far greater. These conditions would have reduced the storm surge by at least several feet, says Mock.

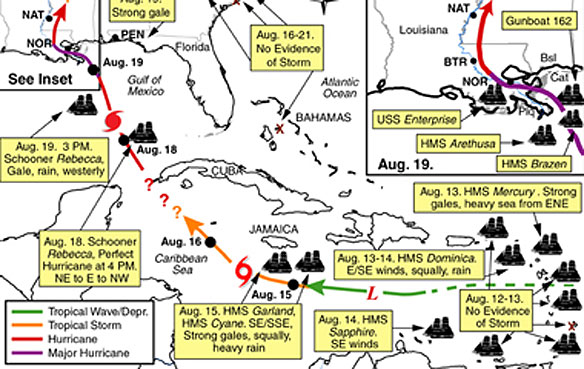

Some of the most valuable sources to Mock’s research were maritime records, which include ship logbooks and ship protests, records submitted by ship captains to notaries detailing damage sustained to goods as a result of weather. Ship logs, kept hour by hour, include data about wind scale, wind direction and barometric pressure.

Because of the war, England bolstered its naval presence, providing Mock, the first academic researcher to conduct historical maritime climate research, with a bounty of records to help him recreate the storm’s path and intensity.

“The British Royal Navy enforced a blockade of American ports during the War of 1812,” said Mock. “The logbooks for ships located in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea had all sorts of valuable information.”

In addition to 12 British Navy logbooks, he was able to use information from logbooks of the USS Enterprise and another from an American merchant vessel. Ship protest records from the New Orleans Notarial Archives provided Mock with some surprising contributions.

“I was initially pretty pessimistic on what I would find in the ship protests,” said Mock. “I thought I’d find a few scraps and be in and out in two days. I was wrong. I found a trove of material and ended up going back eight times.”

Archivists presented Mock with upwards of 100 books for every year, each 800 pages in length and none indexed with the word hurricane. After scouring the records, Mock uncovered nearly 50 useful items related to the 1812 hurricane, including accounts from the schooner, Rebecca, which described the storm in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico in a protest that was filed with notary Marc Lafitte.

It described a 4 p.m. heavy gale that increased to a perfect hurricane wind, with the shifting of winds by noon the next day. The shift of winds from the northeast to the northwest told Mock that the storm track passed to the east of the Rebecca.

Using the logs and protests, Mock was able to correlate the precise location of ships with the hourly weather and create a map of the storm’s path through the Gulf of Mexico.

“Its initial approach was toward Mississippi, but then it turned northwest toward Louisiana as it approached landfall in the afternoon on Aug. 19,” Mock said. “The USS Enterprise had the most detailed wind observations at New Orleans. A change in winds to the southwest around local midnight tells me that the storm center skimmed as little as five kilometers to the west of New Orleans.”

To further understand the hurricane’s formation and dissipation, Mock reviewed records stretching as far north as Ohio and east to South Carolina. Included among them were meteorological records by James Kershaw in Camden, S.C., which are part of the collections of USC’s South Caroliniana Library.

“I wanted to collect data from a wide area to understand patterns, pressure systems and the very nature of the 1812 hurricane,” said Mock. “A better understanding of hurricanes of the past for a wide area provides a better understanding of hurricane formation and their tracks in the future.”

Waveland beach, located in Hancock County, Mississippi, on the Gulf of Mexico. It is part of the Gulfport–Biloxi area. Photo Source: T. Effendi.