By Orrin Pilkey, William Neal, Joseph Kelley and Andrew Cooper

Hurricane Irene left a lasting impression on beaches all along the Eastern Seaboard. The authors of “The World’s Beaches :A Global Guide to the Science of the Shoreline,” explain what kinds of changes late-season beachgoers can expect in the wake of Hurricane-turned-Tropical-Storm Irene.

Looking at the surface of a beach is like reading a history book. The physical processes that shape the beach leave behind all sorts of evidence of their presence.

Currents, the back and forth of the wave “swash” (the water that washes ashore after a wave has broken), wind, and, of course, hurricanes all leave unique and easily identifiable marks.

Those living in the New York-metro area have access to both naturally occurring beaches (including much of the Fire Island National Seashore, some outer Long Island beaches, and Sandy Hook National Seashore in New Jersey) as well as “nourished” — meaning artificially expanded — beaches such as Coney Island, the Rockaways, most of the beaches of Northern New Jersey and many of the beaches on the South Shore of Long Island. When a beach is “nourished,” it means that machinery pumps new sand onto the beach’s surface from the seabed.

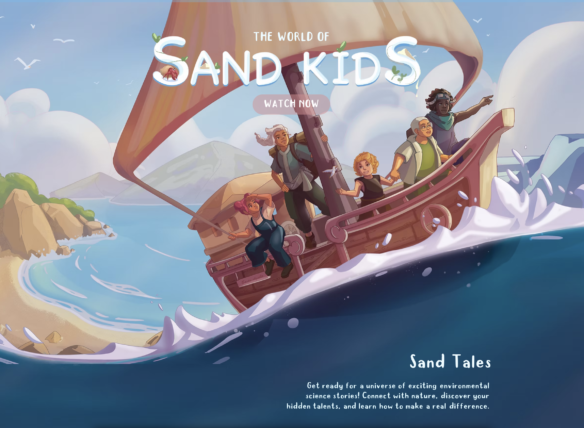

The World’s Beaches : A Global Guide to the Science of the Shoreline

A book by Orrin H. Pilkey, William J. Neal, James Andrew Graham Cooper and Joseph T. Kelley.