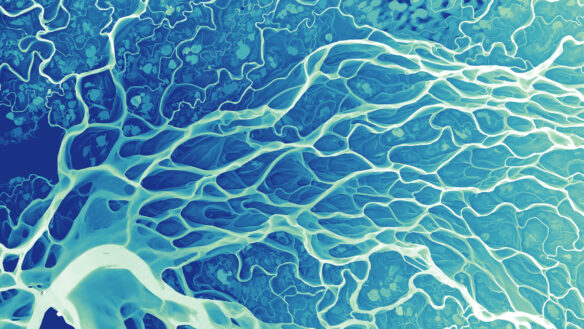

Aerial pictures of North Carolina’s coast, after superstorm Sandy devastated the area. Photo courtesy of: © Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines (PSDS) / WCU

By Orrin H. Pilkey, James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of Geology, Duke University

Co-Author with Rob Young of The Rising Sea (Island Press), and mod

As ocean waters warm, the Northeast is likely to face more Sandy-like storms. And as sea levels continue to rise, the surges of these future storms will be higher and even more deadly. We can’t stop these powerful storms. But we can reduce the deaths and damage they cause.

Hurricane Sandy’s immense power, which destroyed or damaged thousands of homes, actually pushed the footprints of the barrier islands along the South Shore of Long Island and the Jersey Shore landward as the storm carried precious beach sand out to deep waters or swept it across the islands. This process of barrier-island migration toward the mainland has gone on for 10,000 years.

Yet there is already a push to rebuild homes close to the beach and bring back the shorelines to where they were. The federal government encourages this: there will be billions available to replace roads, pipelines and other infrastructure and to clean up storm debris, provide security and emergency housing. Claims to the National Flood Insurance Program could reach $7 billion. And the Army Corps of Engineers will be ready to mobilize its sand-pumping dredges, dump trucks and bulldozers to rebuild beaches washed away time and again.

But this “let’s come back stronger and better” attitude, though empowering, is the wrong approach to the increasing hazard of living close to the rising sea. Disaster will strike again. We should not simply replace all lost property and infrastructure. Instead, we need to take account of rising sea levels, intensifying storms and continuing shoreline erosion.

… We should not simply replace all lost property and infrastructure. Instead, we need to take account of rising sea levels, intensifying storms and continuing shoreline erosion.”

—Orrin H. Pilkey

I understand the temptation to rebuild. My parents’ retirement home, built at 13 feet above sea level, five blocks from the shoreline in Waveland, Miss., was flooded to the ceiling during Hurricane Camille in 1969. They rebuilt it, but the house was completely destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. (They had died by then.) Even so, rebuilding continued in Waveland. A year after Katrina, one empty Waveland beachfront lot, on which successive houses had been wiped away by Hurricanes Camille and Katrina, was for sale for $800,000.

That is madness. We should strongly discourage the reconstruction of destroyed or badly damaged beachfront homes in New Jersey and New York. Some very valuable property will have to be abandoned to make the community less vulnerable to storm surges. This is tough medicine, to be sure, and taxpayers may be forced to compensate homeowners. But it should save taxpayers money in the long run by ending this cycle of repairing or rebuilding properties in the path of future storms. Surviving buildings and new construction should be elevated on pilings at least two feet above the 100-year flood level to allow future storm overwash to flow underneath. Some buildings should be moved back from the beach.

Respecting the power of these storms is not new. American Indians who occupied barrier islands during the warm months moved to the mainland during the winter storm season. In the early days of European settlement in North America, some communities restricted building to the bay sides of barrier islands to minimize damage. In Colombia and Nigeria, where some people choose to live next to beaches to reduce exposure to malarial mosquitoes, houses are routinely built to be easily moved.

We should also understand that armoring the shoreline with sea walls will not be successful in holding back major storm surges. As experience in New Jersey and elsewhere has shown, sea walls eventually cause the loss of protective beaches. These beaches can be replaced, but only at enormous cost to taxpayers. The 21-mile stretch of beach between Sandy Hook and Barnegat Inlet in New Jersey was replenished between 1999 and 2001 at a cost of $273 million (in 2011 dollars). Future replenishment will depend on finding suitable sand on the continental shelf, where it is hard to find.

And as sea levels rise, replenishment will be required more often. In Wrightsville Beach, N.C., the beach already has been replenished more than 20 times since 1965, at a cost of nearly $54.3 million (in 2011 dollars). Taxpayers in at least three North Carolina communities — Carteret and Dare Counties and North Topsail Beach — have voted down tax increases to pay for these projects in the last dozen years. The attitude was: we shouldn’t have to pay for the beach. We weren’t the ones irresponsible enough to build next to an eroding shoreline.

This is not the time for a solution based purely on engineering. The Army Corps undoubtedly will be heavily involved. But as New Jersey and New York move forward, officials should seek advice from oceanographers, coastal geologists, coastal and construction engineers and others who understand the future of rising seas and their impact on barrier islands.

We need more resilient development, to be sure. But we also need to begin to retreat from the ocean’s edge.

Aerial pictures of New Jersey’s coast, Mantoloking, after superstorm Sandy devastated the area. Photo courtesy of: © Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines (PSDS) / WCU

Originally Published in, The New York Times

The World’s Beaches: A Global Guide To The Science Of The Shoreline

A Book by Orrin H. Pilkey, William J. Neal, James Andrew Graham Cooper And Joseph T. Kelley.