Shipbreaking, Gadani beach, Pakistan. Photo source: ©© Michael Foley Photography

By Mike Carlowicz, NASA / Earth Observatory;

Tens of thousands of ships ply the world’s oceans, bays, and rivers. Close to 50,000 of them are used for transporting goods to markets, and another 30,000 are cruise ships, ferries, fishing boats, and other working vessels. Neither number accounts for military ships.

But what happens when those ships have become too old or too expensive to operate? In most cases, they end up on the shores of Asia…literally.

Ships are rich with steel, which makes up about 75 to 85 percent of their mass. When a ship is retired and dismantled, that steel is cut up and usually melted and re-forged for other uses. Ships are also full of machinery, furniture, wiring, instruments, fittings, and other objects that can be put to other maritime and land uses.

Five countries—Turkey, China, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh—dominate this ship-recycling market, absorbing about 97 percent of all of the tonnage.

Along the coast of Bangladesh, just north of Chittagong, there are no vast industrial shipyards. But there are gently sloping beaches and shallow waters. Unwanted and old ships are intentionally run aground here so that they can be dismantled and recycled. Workers dissect these vast metal hulks by hand, rarely using more than blowtorches and simple tools. The work is arduous at best, and life-threatening at worst.

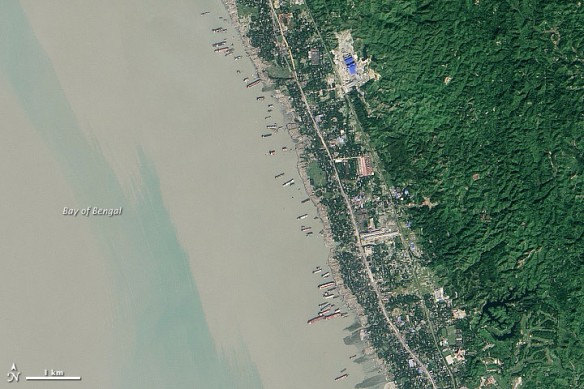

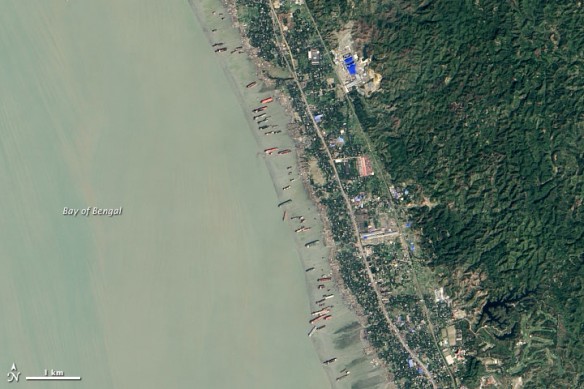

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 satellite acquired these two images of ship-recycling in coastal Bangladesh on December 1, 2013, and February 19, 2014.

Image acquired September 1, 2013.

Image acquired December 19, 2014.

Turn on the image comparison tool and note how new ships have arrived, others have disappeared, and a few have moved slightly. Several appear to be considerably smaller, likely because disassembly is in progress. Note also the difference in the color of the water near the shore. The lighting changes with the seasons, as does the amount of sediment in the water. Tides and water depth also may have been different at the time of each image.

Proponents of these operations note that they are recycling and returning old materials into a new life in the free market. Bangladesh has little to no natural supplies of iron ore, and as much as 70 percent of the nation’s steel is forged from these scraps. Close to 200 ships were dismantled in Bangladesh in 2013, and thousands of ship-breaking workers earn significantly more than the average wage in this impoverished country.

However, critics point to dangerous working conditions that lead to scores of deaths each year, and wages that are well below what is paid in other countries. They also note that there are few to no environmental protections for the health of workers or the coastal waters, which are filling with the runoff of oil, asbestos, and other chemicals.

You can see close-up footage of these ship-breaking operations in videos from the BBC and CBS News.

Original Article, NASA / Earth Observatory

Chittagong Beach Ship Breaking Yards, Bangladesh, Guardian UK (05-05-2012)

Stretched along 12 miles of what just a decade ago was a pristine sandy beach, ore carriers, container ships, gas tankers, cruise liners and cargo ships of every size and description are being dismantled by hand in 140 similar yards, at Chittagong beach Ship Breaking Yard, Bangladesh, the world’s second largest ship breaking area. Every year more than 250 redundant ships, many from Britain and Europe, come here to be broken up…

The Ship-Breakers, National Geographic (05-2014)

In Bangladesh men desperate for work perform one of the world’s most dangerous jobs…

New EU Rules ‘Fail’ Against Shipbreaking Dangers, IPS News (07-17-2013)

The European Parliament’s Environment Committee voted last in favour of a proposal aiming to put an end to European ships being recklessly scrapped in developing countries…

“Ship yard, Bangladesh”: A Photo by Jana Asenbrennerova, National Geographic Photo Contest 2010