Guest Opinion | Kim Steinhardt | 14 May 2023 (updated 18 May 2023)

Remember what it was like as a kid when a grownup told you “Because I said so”?

Well, a newly constituted majority of the U.S. Supreme Court has recently flexed its ideological muscle, upending 50 years of precedent guiding its decisions, and basically told us “Because I said so.”

This quiet revolution by an activist majority, deciding cases based on primarily political grounds rather than on the constraints of facts and legal precedent, will have grave impact on environmental policymaking – as well civil rights, healthcare, safety, education, elections, technology, finance, and economics.

Somewhat hidden in the long shadow of the court’s overturning Roe v Wade last summer was the decision in EPA v West Virginia. Just as it had done in overturning women’s reproductive rights, the new majority stripped away all pretense of adhering to well-settled precedent in its quest to achieve long sought political goals. These cases were not decided on the basis of new, compelling legal or factual reasons for rejecting settled law, as has historically been the bedrock of Supreme Court practice. These cases were decided simply because the court could: the newly appointed justices provided the number of votes needed to achieve previously unattainable specific policy outcomes.

In EPA v West Virginia, the court decided that in certain cases it would no longer adhere to its long-standing rule of deferring to the professional expertise of administrative agencies and, instead, substitute its own judgment whenever it chose to disagree with an agency on policy.

This new approach reversed 50 years of the Supreme Court’s own often-cited precedent that required it to defer to the expertise of agencies, even if it disagreed with the result, unless the agencies’ actions were arbitrary or capricious. This is a dramatic change to reviewing challenged environmental laws – as well as other laws, rules, and regulations put forth by specialized governmental agencies acting pursuant to legislation.

Why does this matter? Isn’t it just a legal technicality? After all, aren’t judges already making their own judgments all the time?

Yes and no. They do make judgments, but they are restrained by precedent, that is, the framework of former cases setting specific standards to apply when judgments are to be made in considering cases with new facts or where there are legal ambiguities.

Up until EPA v West Virginia, courts were not free to find a different outcome just because there were enough votes to revisit a previous position, or a particular judge felt like he or she could. The approach has not been “just because we can.”

Under the current majority’s new standard for review, dubbed the “Major Questions Doctrine,” a judge is free to substitute his or her judgment for the experts whenever the issue is deemed to be a “major question,” loosely defined as having vast political or economic significance.

But since the judge gets to decide what issues fit that description, under this standard a judge has the luxury of determining when he or she gets to disregard the agency’s expertise and make an independent judgment more to his or her liking. And this new approach applies to all types of issues, not just environmental policies.

The prior standard was at its core a way of recognizing the fundamental separation of powers between the judiciary, the executive, and the legislative branches of government: it limited the judiciary’s role when scrutinizing executive branch actions implementing legislative branch laws. The court has not demonstrated that the new standard is anything other than a tool to strengthen its hand vis-à-vis the other branches of government when intervening to reverse executive or legislative actions with which it disagrees. It is simply a formula contrived to elevate whatever issues it chooses to target, ideologically, into a position such that it can come to its preferred conclusion regardless of expertise.

In the specific case of EPA v West Virginia, the majority applied this new standard and struck down the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, a well-studied effort intended to implement portions of the federal Clean Air Act and reduce air pollution from coal fired power plants as part of a multi-faceted EPA attack on the negative impacts and sources of climate change.

But many other cases will arise in which the court can look to this new doctrine to overturn the careful work of the administrative and legislative experts based on political rather than legal or scientific criteria. Court challenges to innovative environmental initiatives and programs have become an increasingly common tactic used by staunch climate change deniers and others determined to substitute their own preferences even after failing to make persuasive factual or legal cases to policymakers.

Many of the programs and policies being developed to confront the challenges of climate change are implemented through agency rules and regulations subject to this new doctrine. It is likely to throw serious roadblocks into the variety of actions that will be necessary if we are to successfully overcome the urgent challenges of climate change.

With this recent case, the new Court majority has dramatically altered the role of the federal judiciary. The prior approach was part of a legal safety net assuring that disputed government actions were legitimate exercises of discretion by agencies following the law. Now, on “major questions” the role will be to decide whether the judge agrees or disagrees with the action.

Sounds a lot like “Because I said so.”

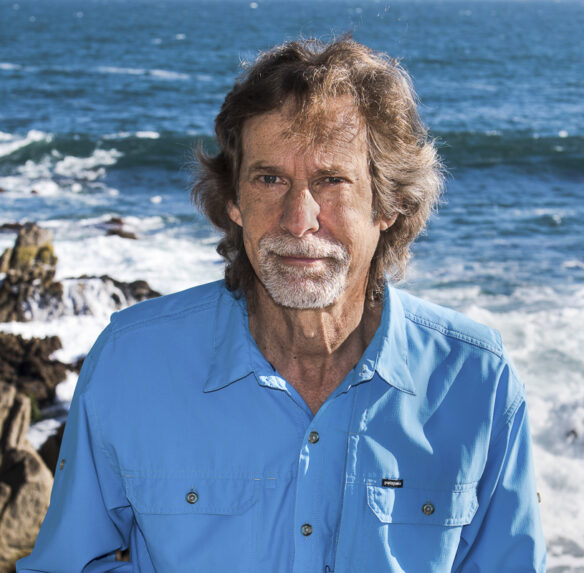

Kim Steinhardt is a former administrative law judge turned environmental writer and marine wildlife photographer. His focus on sea otters has been recognized by National Geographic’s Explore My World Series and elsewhere. His most recent book is a true story for children: Sabby the Sea Otter – A Pup’s True Adventure and Triumph, and he is co-author of The Edge: The Pressured Past and Precarious Future of California’s Coast. He teaches law classes emphasizing public interest policymaking, legislation, and ocean advocacy.

Kim Steinhardt is a former administrative law judge turned environmental writer and marine wildlife photographer. His focus on sea otters has been recognized by National Geographic’s Explore My World Series and elsewhere. His most recent book is a true story for children: Sabby the Sea Otter – A Pup’s True Adventure and Triumph, and he is co-author of The Edge: The Pressured Past and Precarious Future of California’s Coast. He teaches law classes emphasizing public interest policymaking, legislation, and ocean advocacy.

Website: kimsteinhardt.com