Excerpt:

Rotifers could be accelerating risk by splitting particles into thousands of potentially more dangerous nanoplastics.

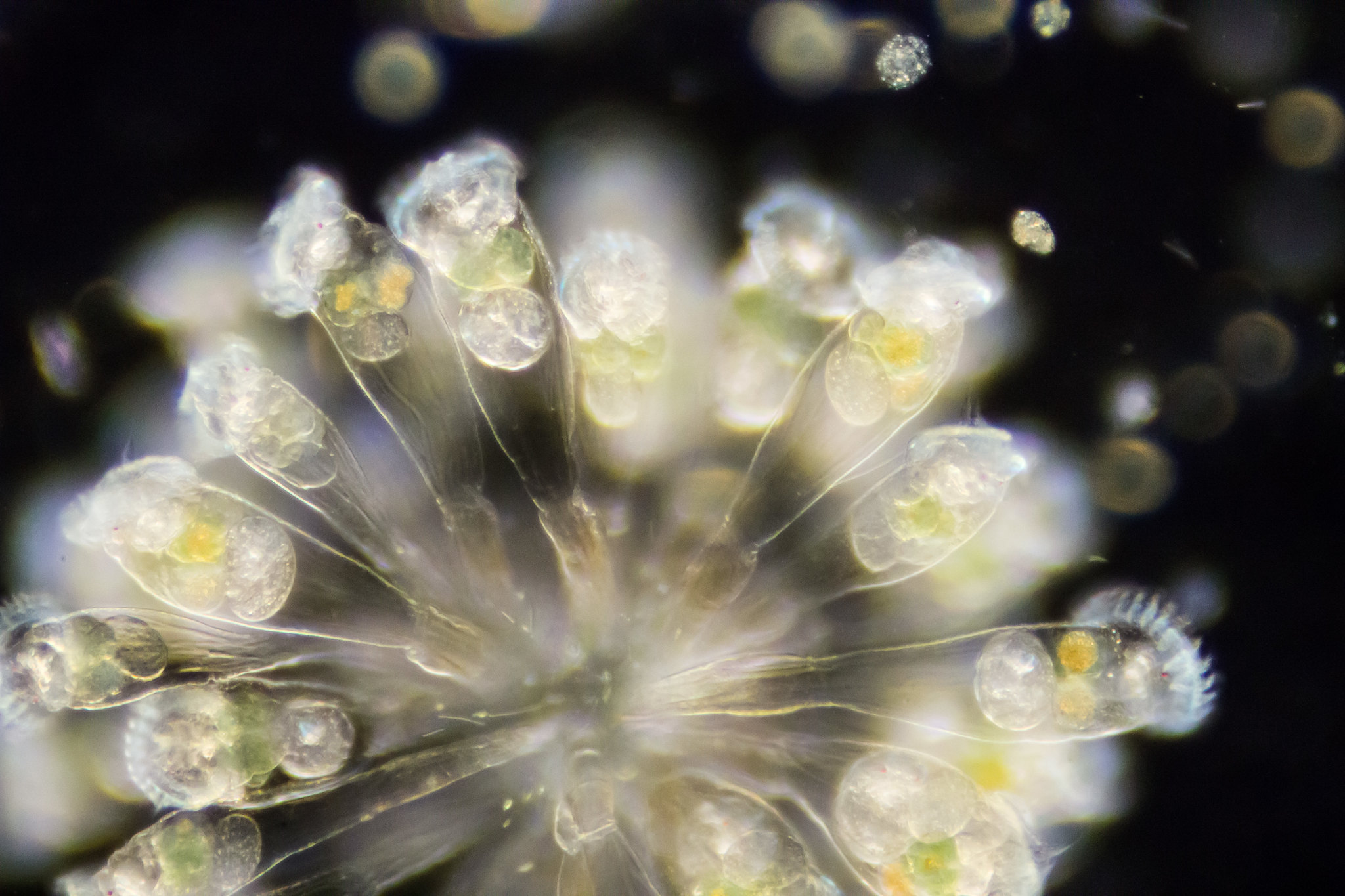

A type of zooplankton found in marine and fresh water can ingest and break down microplastics, scientists have discovered. But rather than providing a solution to the threat plastics pose to aquatic life, the tiny creatures known as rotifers could be accelerating the risk by splitting the particles into thousands of smaller and potentially more dangerous nanoplastics.

Each rotifer, named from the Latin for “wheel-bearer” owing to the whirling wheel of cilia around their mouths, can create between 348,000 and 366,000 nanoplastics – particles smaller than one micrometre – each day.

The animals are microscopic, ubiquitous and abundant, with up to 23,000 individuals found living in one litre of water, in one location. The researchers, from a team led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst, calculated that in Poyang Lake, the largest lake in China, rotifers were creating 13.3 quadrillion of these plastic particles every day.

Plastic can take up to 500 years to decompose. As it ages, tiny pieces break off. Physical and chemical processes are known to break them down, including when exposed to sunlight or when waves grind bits of plastic against rocks, beaches or other obstacles floating in the ocean.

The scientists sought to examine what role aquatic life might play in microplastic creation, especially after the discovery in 2018 that Antarctic krill are able to break down polyethylene balls into fragments of less than one micrometre. Baoshan Xing, a professor of environmental and soil chemistry at the University of Massachusetts Amherst’s Stockbridge School of Agriculture, said they decided to look at rotifers because they had specialised chewing apparatus similar to krill. They wanted to test the hypothesis that rotifers, of which there are 2,000 species worldwide, could also break down plastic.

“Whereas Antarctic krill live in a place that is essentially unpopulated, we chose rotifers in part because they occur throughout the world’s temperate and tropical zones, where people live,” said Xing, the paper’s senior author.

The animals mistake microplastics – fragments of less than 5mm in diameter – for algae, he said.

After exposing marine and freshwater species of rotifers to a variety of different plastics of different sizes, they found all could ingest microplastics of up to 10 micrometres (0.01mm), break them down and then excrete thousands of nanoplastics back into the environment. Polyethylene microplastics from food containers as well as nanoplastics were detected in the rotifers’ bodies.