Excerpt:

Some glaciers on the island are melting at double the rate of just a few decades ago.

Greenland’s mountain glaciers and floating ice shelves are melting faster than they were just a few decades ago and becoming destabilized, according to two separate studies published this week.

The island’s peripheral glaciers, located mostly in coastal mountains and not directly connected to the larger Greenland ice sheet, retreated twice as fast between 2000 and 2021 as they did before the turn of the century, according to a study published on Thursday.

“It got a lot harder to be a glacier in Greenland in the 21st century than it had been even in the 1990s,” said Yarrow Axford, a professor of geological sciences at Northwestern University and a co-author of the paper, published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Dr. Axford’s team found that glaciers in southern Greenland have become shorter by 18 percent on average since 2000, and glaciers elsewhere on the island have become shorter by 5 to 10 percent.

“These glaciers react really quickly to changes in climate,” Laura Larocca, the lead author and a NOAA postdoctoral fellow at Northern Arizona University, said. Since 2000, temperatures in the Arctic have risen twice as fast as the global average temperature.

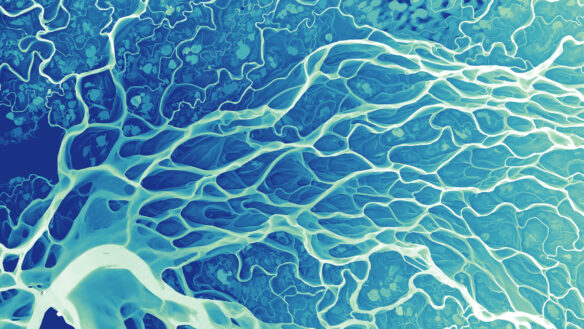

The researchers compared historical photos dating back to the 1930s with modern satellite measurements of more than 1,000 glaciers. By converting both types of images into digital maps, the researchers could measure how far the glaciers’ end points had retreated over the years.

Ice melting into the ocean from Greenland is one of the biggest contributors to global sea level rise. Glaciers there are also important locally for maintaining natural ecosystems and biodiversity, and for providing electricity through hydropower. Some Greenlanders even depend on glaciers’ meltwater for drinking water. As the ice melts, more water will temporarily become available, but if warming is left unchecked the ice and its meltwater will eventually run out.

Peripheral glaciers can be an “early warning system” for the rest of Greenland’s snow and ice, Dr. Axford said. The individual glaciers are small compared with the vast ice sheet covering the country’s interior, although some could still dwarf entire cities, and respond more directly to the warming atmosphere. These glaciers only represent about 4 percent of Greenland’s total ice cover, but account for about 14 percent of the island’s ice loss. As a result, they’re contributing disproportionately to sea level rise.

That could change as the ice sheet itself becomes less stable. Greenland’s northern coast is buttressed by floating ice shelves that prevent inland glaciers, which are part of the ice sheet, from flowing freely into the Arctic Ocean.

These ice shelves have shrunk in volume by more than 35 percent since 1978, according to a separate study published Tuesday in Nature Communications. The ice is mostly melting from the bottom, as the ocean underneath the floating shelves warms. Three ice shelves in northern Greenland have already collapsed almost entirely, all within the past 20 years. After one of these collapses, ice loss from the glacier behind the shelf more than doubled.

“It’s like removing bricks from the ice dam,” said Romain Millan, a glaciologist at the Université Grenoble Alpes in France and the lead author of the paper.

The research published this week builds on work by Anders Bjork, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Copenhagen who was a co-author of both papers. He has been traveling to Greenland since 2006 and said evidence of shrinking glaciers was clearly visible all over the landscape…