Excerpt:

Organized crime is mining sand from rivers and coasts to feed demand worldwide, ruining ecosystems and communities. Can it be stopped?

Transnational security investigator Abdelkader Abderrahmane set out from the Moroccan city of Kenitra with two research assistants to inspect sand-mining sites on the Atlantic Ocean coast. They drove across the dry, flat terrain for six kilometers, the last stretch on a rutted dirt road that had them crawling in low gear, windows closed against the hot dust. The beach dunes where they were headed lay beyond a rise. As they approached, a man wearing a gendarme cap suddenly appeared to their right, speeding toward them on an all-terrain vehicle. With angry gestures, he forced them to a stop. “Why are you here?!” he demanded. “There’s nowhere to go.” One assistant said they just wanted to visit the beach and the nearby tourist camp. The gendarme shook his head: no further.

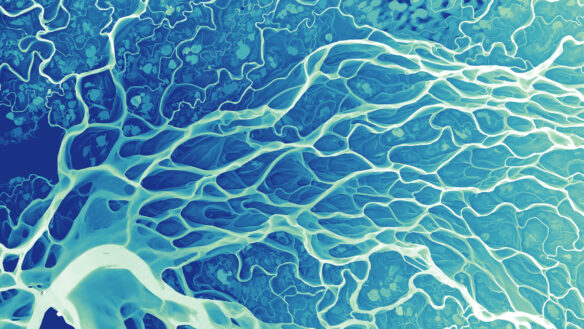

They turned around and began to creep back down the rough road, but as soon as the gendarme was out of sight they turned off and snuck along a hidden side of the ridge. About 400 meters further they stopped and cut the engine. Abderrahmane walked quietly to the crest of the bluff to peer down, keeping low to avoid being seen. Despite all his research into illegal sand mines, he was unprepared for the scene below. Half a dozen dump trucks scattered across a deeply pitted moonscape were filled high with brown sand. Just beyond lay the light blue sea. Abderrahmane was stunned by the “major disfiguration” of the dunes, he told me later on a video call. “It was a shock.”

Part of his shock came from the sight of desecrated nature, but part came from seeing the brazenness of trucks hauling sand in full daylight. “You cannot illegally mine sand in daylight if you don’t have people helping you,” he says—people in high places. “Big companies are being protected, perhaps by ministers or deputy ministers or whoever. It’s a whole system.” Everyone in the sand-trafficking market “benefits from it, from top to bottom.”

For the past 15 years the slender, bespectacled Abderrahmane has studied environmental trade and crime for the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), an African research and policy advisory organization based in South Africa. ISS papers showed how environmental degradation can fuel tensions among people and compromise security. But until a few years ago Abderrahmane had never heard of sand trafficking. He had been in Mali doing fieldwork on the drug trade when a source noted that most cannabis in Mali came from Morocco and that sand trafficking was also a major market in that country, with drug traffickers involved. “I think that when you talk about sand trafficking, most people would not believe it,” Abderrahmane says. “Me included. Now I do.”

Very few people are looking closely at the illegal sand system or calling for changes, however, because sand is a mundane resource. Yet sand mining is the world’s largest extraction industry because sand is a main ingredient in concrete, and the global construction industry has been soaring for decades. Every year the world uses up to 50 billion metric tons of sand, according to a United Nations Environment Program report. The only natural resource more widely consumed is water. A 2022 study by researchers at the University of Amsterdam concluded that we are dredging river sand at rates that far outstrip nature’s ability to replace it, so much so that the world could run out of construction-grade sand by 2050. The U.N. report confirms that sand mining at current rates is unsustainable…