Excerpt:

In deep water and in the shallows, corals cooked by last year’s extreme heat are not doing great.

In the northern hemisphere, the summer of 2023 was the hottest on record. In the Caribbean, coral reefs sat in sweltering water for months—stewing in a dangerous marine heatwave that started earlier, lasted longer, and climbed to higher temperatures than any seen in the region before. In some places, the water was over 32 °C—as toasty as a hot tub. Ever since the water started to warm, researchers and conservationists have been anxiously watching to see how the debilitating heat has affected the region’s corals.

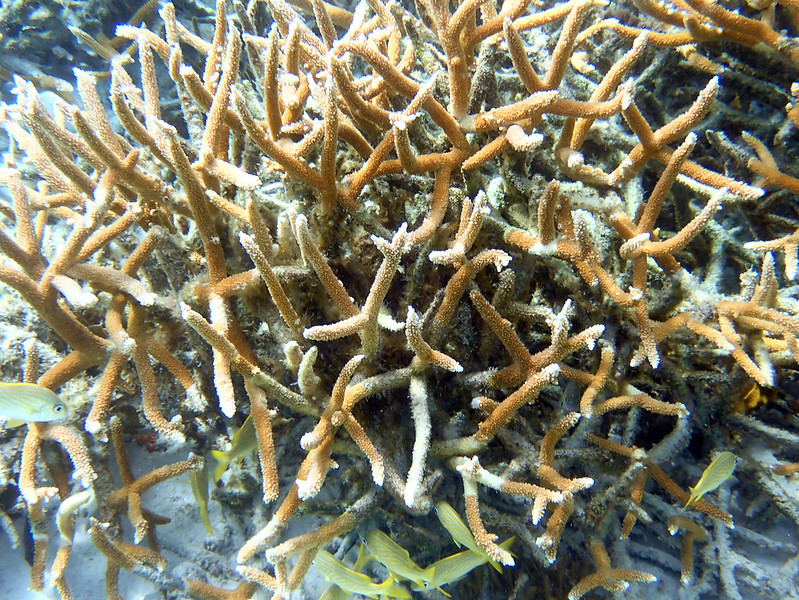

For many Caribbean corals, last year’s heat proved too much to bear. The more time corals spend in hot water, the more likely they are to bleach, turning white as they expel the single-celled algae that live within their tissues. Without these symbiotic algae—and the energy they provide through photosynthesis—bleached corals starve. Survival becomes a struggle, and what had been a healthy thicket of colorful coral can turn into a tangle of skeletons.

Corals can recover from bleaching. But while some Caribbean corals survived last year’s bleaching and others were unaffected, multitudes perished. And for many corals, the harrowing experience isn’t even over.

Lorenzo Álvarez-Filip, a marine ecologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, says that, for a coral, recovering after bleaching is like recuperating from a long illness. It takes time. Yet even now, several months after the water has cooled to temperatures that no longer stress corals, researchers across the Caribbean are still finding bleached corals living in limbo…