Excerpt:

Stretchy seaweed, reverse vending machines, QR-coded take-out boxes: They’re how we can break society’s absurd addiction to single-use plastics.

A plastic bag might be the most overengineered object in history. Some years back, I stopped by a French deli to buy some big chunks of cheese and carried them home in a plastic bag. The cheese was so heavy that the bag stretched and bulged, and the handle dug painfully into my hands. But the bag didn’t break. That’s because of the magical chemistry of plastic—essentially, oil turned solid, with carbon and hydrogen atoms that line up in repeating units to form long, noodle-like molecules.

These molecules are pliable and strong, which is what makes plastic so widely useful. And so durable: I unpacked the hunks of Camembert and Havarti and shoved the bag into the back of a kitchen drawer. When I stumbled upon it a few weeks ago, it was still pristine. Of course it was. Plastic bags can last, intact and usable, for decades.

Which is … nuts, right? We create a bag rugged enough to span decades and then use it for minutes before shoving it in a drawer or, more likely, sending it off to a landfill, where it might break into fragments that stick around for hundreds of years. Like I said: the most overengineered object in history.

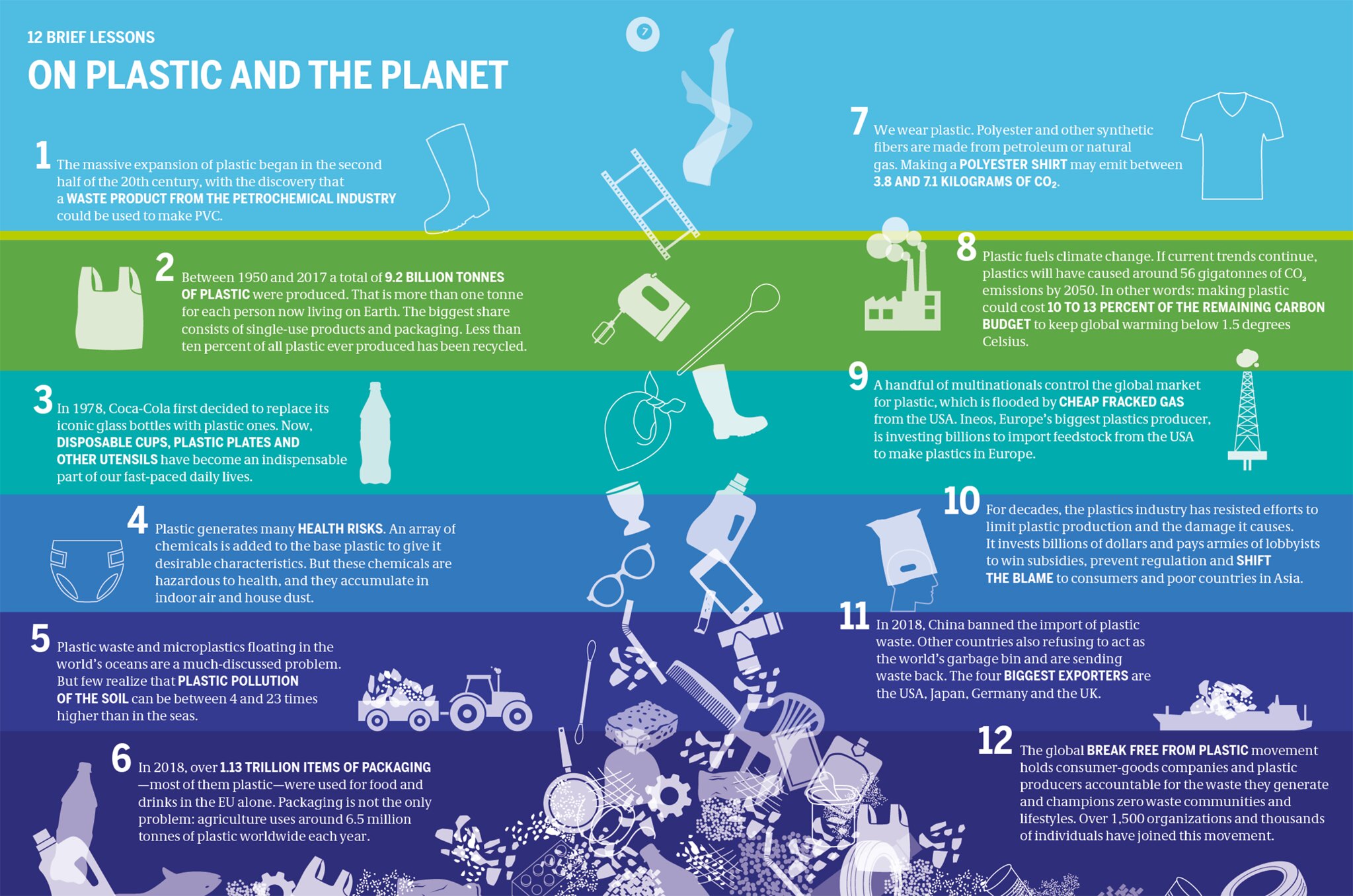

The environmental problem of “single-use plastics” haunts the public imagination like a spectral wolf. And no wonder—the sheer welter of everyday objects we make from plastic is astonishing. There’s plastic in grocery bags, obviously, but also in yoga pants and car tires and building materials and toys and medical products. The transition came on quickly: Plastic use was comparatively small until the 1970s, when it exploded, tripling by the 1990s. Then it went into overdrive, and in the next 20 years we used as much plastic as we had in the previous 40. We now crank out more than 500 million tons of plastic waste a year. Globally, only 9 percent of plastics are recycled. The rest go into landfills or get incinerated, pumping toxic fumes into the air, usually in poor neighborhoods. A significant chunk also ends up in the ocean, which has already amassed as much as 219 million tons of the stuff—wrappers washing up on shorelines, chunks eaten by fish, islands of plastic forming in watery gyres at sea.

It’s a lot. Too much, many of us agree. And if we want to begin unwinding the plastic revolution? One good place to start is all those single-use products—because, according to the UN Environment Programme, they make up fully 36 percent of the plastics we use every year.

They’re not easy to walk away from, in part because we use so many types in so many places. We’ve got “thin films” like bags, thicker plastics in take-out bowls, multi-layered plastic containers for grocery store meat, and see-through polyethylene terephthalate bottles for soda and water. Each has its own chemical properties, molecular makeup, and performance specs. A single replacement for all that packaging? It doesn’t exist.

What does exist, though, is a set of promising developments in the management, as it were, of single-use stuff.

It’s a war on three fronts: Replace some of our single-use plastics with truly compostable materials. Replace another chunk with reusable containers, like metal or glass. And, finally, tweak the economic incentives so plastic recycling actually works. This isn’t my battle plan; it’s a theme I heard over and over as I spent the past year talking to scientists, inventors, entrepreneurs, and policy folk.

None of these ploys is a slam dunk. They’ll need not only innovation but also binders full of smart government incentives and regulation—all of which, of course, will be resisted by petroleum firms. But if you add up all these unplastic developments, you’ll find grounds for cautious optimism: We’ve got a path to a world less littered with deathless plastic waste…