Excerpt:

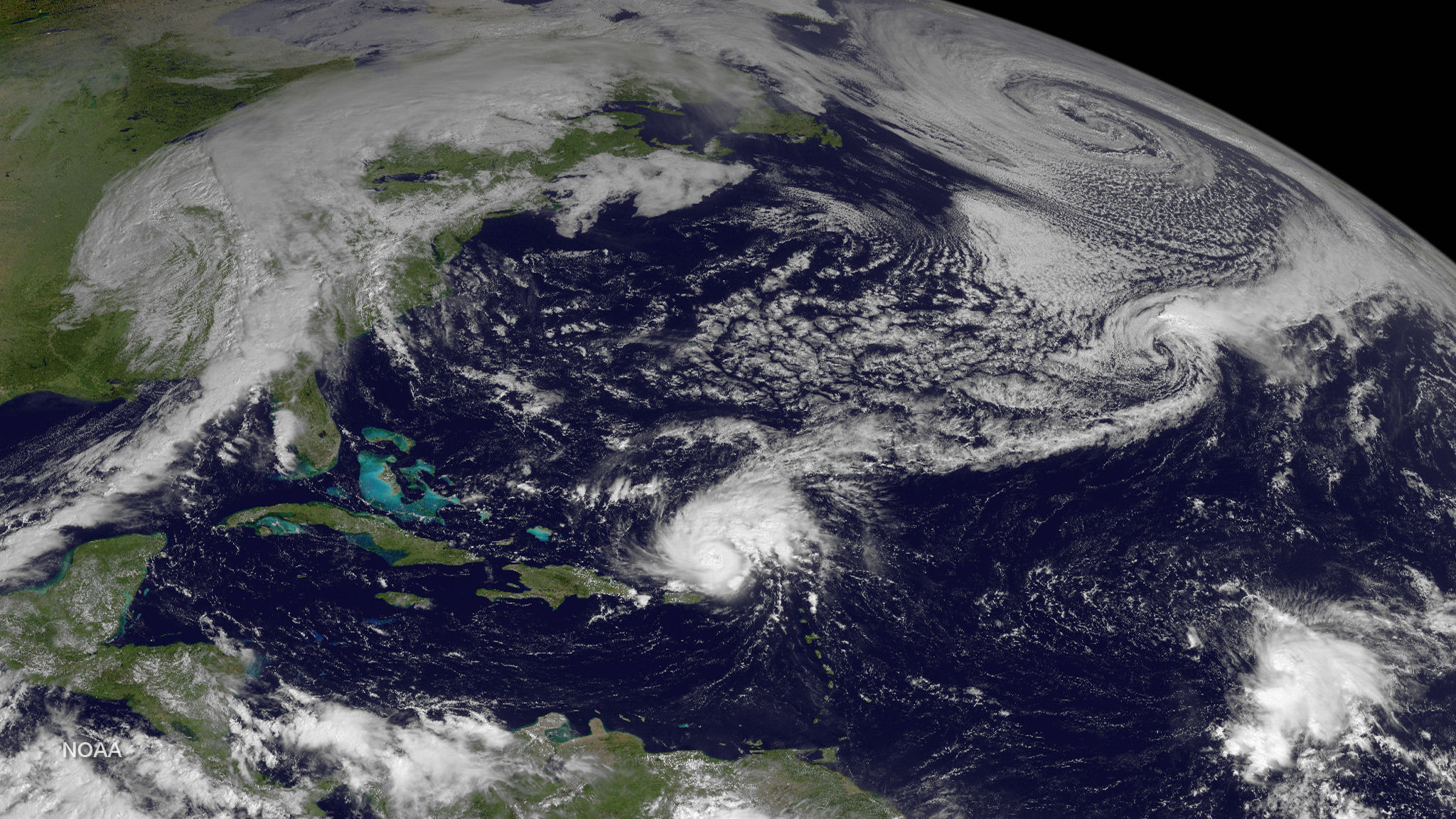

Cyclones aren’t just made of wind and rain — they’re full of data. That’ll help researchers improve the forecasts that determine whom to evacuate.

Just a few weeks into the hurricane season, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, has declared the end of El Niño, the warm streak of water in the Pacific that influences global weather. That makes an already dire outlook for cyclones even more dangerous — in April, scientists forecasted five major hurricanes and 21 named storms in the North Atlantic alone — because El Niño tends to suppress the formation of such tempests.

NOAA now predicts a 65 percent chance of La Niña, which is favorable for cyclones, developing between July and September, when such events are most common. (La Niña is a band of cool water forming in contrast to El Niño’s warm band.) At the same time, sea surface temperatures remain extraordinarily high in the Atlantic — the kind of conditions that power monster storms.

The Atlantic is primed for a brutal hurricane season. But these cyclones aren’t just made of devastating winds and rains — they’re full of invaluable data that scientists will use to improve forecasting, giving everyone from local meteorologists to federal emergency planners better information to save lives.

Such insights would be particularly critical if, for instance, a hurricane rapidly intensifies — defined as an increase in sustained wind speeds of at least 35 mph in 24 hours — just before it reaches shore and mutates from a manageable crisis into a deadly one. “Those cases right before landfall, where people are most vulnerable, is the nightmare scenario,” said Christopher Rozoff, an atmospheric scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who models hurricanes. “That’s why it’s of such great interest to improve this, and yet it’s been a huge forecasting challenge until somewhat recently…”