Excerpt:

KALALOCH, PRONOUNCED “CLAY-LOCK,” is a broad, sandy, beloved beach on the upper half of Washington’s coastline, sitting at a latitude of 47.61 degrees north: exactly 93.9 miles due west of Pike Place Market.

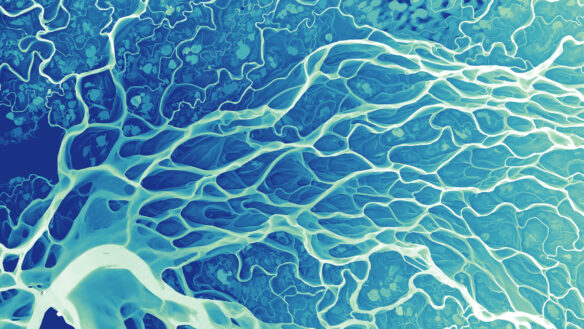

That slice of shore is part of Olympic National Park’s “coastal strip,” 65 miles of federally designated wilderness with a wide range of habitats — rocky outcroppings, tide pools, muddy estuaries — and one of the most biologically diverse marine environments on the West Coast. Just the seaweeds and invertebrates number over 750 species.

The beach at Kalaloch is home to razor clams (there used to be a clam cannery until the great windstorm of 1921 literally blew it away) and other creatures living in the sand, making it a popular fatten-up spot for migrating birds.

For at least the past century, it’s also been a popular resting spot for tourists.

In 1928, 25 years before Kalaloch would become part of Olympic National Park, the Becker family built nine cabins on sediment bluffs overlooking the beach. A night’s stay there cost $2, which included a wood stove for heat and a communal bathroom for visitors’ toilet and shower needs.

No roads went to Kalaloch at the time. Most people arrived by boat.

Fast forward through 95 years: The Olympic Loop Highway got built (1931). The National Park Service purchased the coastal strip, adding it to Olympic National Park (1953). The park service bought the Becker property, which by then included a lodge, a gas station and a grocery store (1978).

These days, Kalaloch is the third-most-visited of Olympic National Park’s nine districts (283,096 visitors in 2022), behind Lake Crescent (841,199) and Hurricane Ridge (329,226), and just above the Hoh (272,867).

Kalaloch Lodge, run on a concessionaire’s contract by the global entertainment/hospitality company Delaware North (whose holdings range from resorts in Australia to the food service at Climate Pledge Arena in Seattle), has grown into a beachfront hotel with a restaurant overlooking the ocean, a small grocery store, a campground and nearly 50 cabins sitting on the same bluffs where the Beckers built their rustic resort 95 years ago.

Except there’s less bluff. And less of it every year.

Erosion has been eating at those bluffs since long before the Beckers — but the rate of erosion has been accelerating, forcing the National Park Service (NPS) to take a hard look at the future of Kalaloch Lodge.

Earlier this year, NPS ordered the immediate closure of five cabins near the bluff’s retreating rim, with plans to demolish them and 11 others in the coming months — and perhaps the rest in the not-too-distant future.

Seems like a good idea. On a recent visit to Kalaloch, the bluff faces were sheared off and raw, with big chunks of freshly fallen sediment lying on the beach below. A few cabins were peeking over the ragged edge, as if waiting for high tide to jump into the ocean.

“IT’S A ROUGH CALCULATION, but we think we’re losing 4 to 10 feet of bluff a year,” says Roy Zipp, acting deputy superintendent of Olympic National Park. “But it’s a stochastic process, the way a lot of natural processes are — long periods of calm, and then you’ll get a bad winter storm and lose 5 feet of bank…”