Excerpt:

Anemones, sponges, and jellyfish are bleaching throughout the Everglades amid record temperatures. It’s a troubling sign for Florida Bay and beyond.

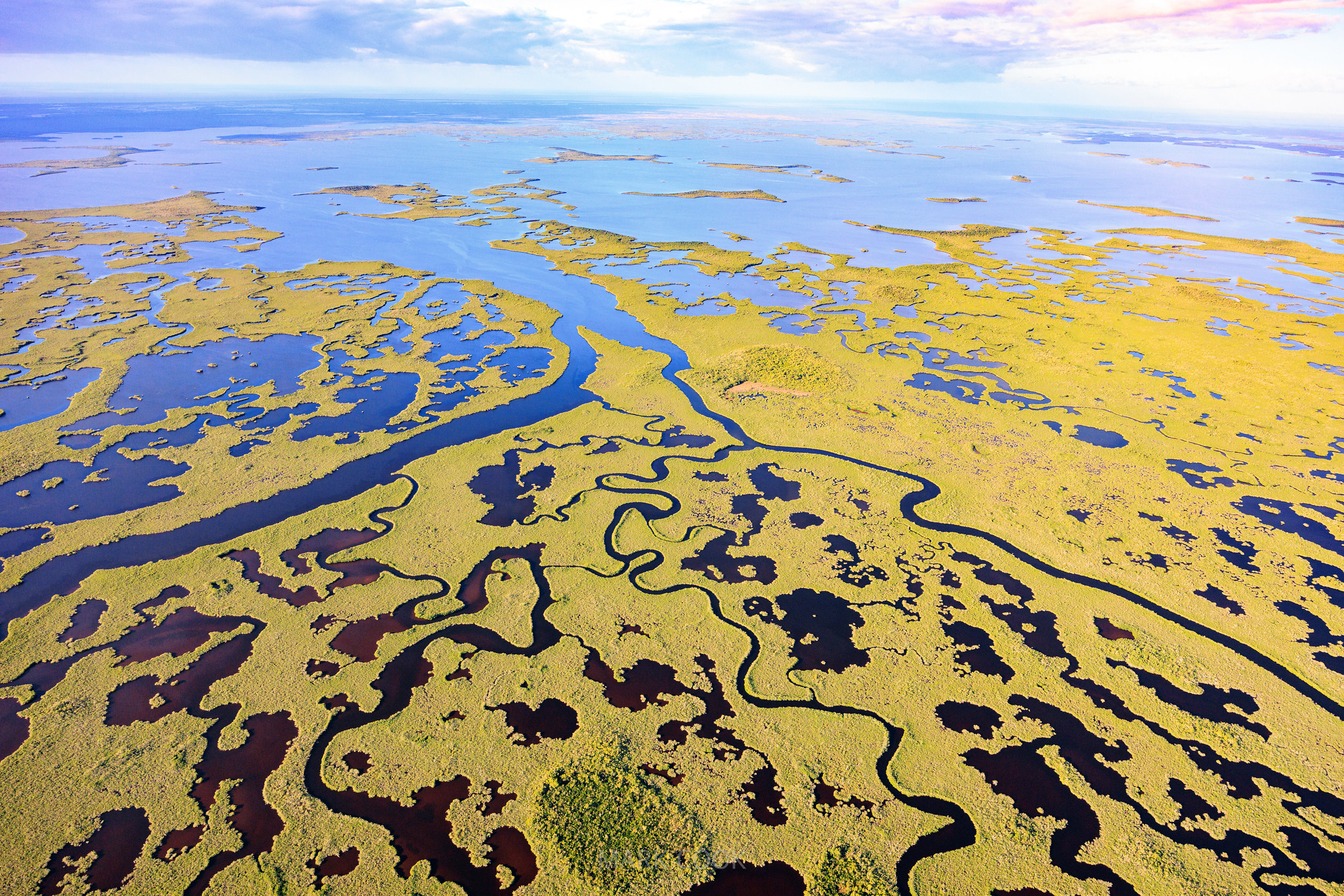

Summer afternoons on Florida Bay are a wonder. The sky, bright blue and dotted with clouds, meets the glassy water in a blur of blue that melts away any sign of the horizon. Wading birds rustle in the verdant branches of mangroves. Beneath the surface, fish and other creatures dart among tangled mangrove roots adorned with colorful sponges and corals. Out in the shallow flats, redfish forage for crabs, snails, and shrimp hidden in fields of seagrass as manatees graze and bottlenose dolphins hunt.

But this vast estuary, which by some estimates stretches at least 800 square miles — roughly the size of Tokyo — and comprises about one-third of Everglades National Park has looked very different lately. In the mangroves, anemones and jellyfish, stressed by unprecedented water temperatures, appear ghostly white. Suffocated fish and soupy patches of dead seagrass litter the sandy flats. Sponges and coral languish beneath thick sheaths of algae.

This summer, as water temperatures across the Everglades reached triple digits, much of the nation’s attention focused on the Atlantic side of the Keys, where rapid bleaching devastated much of the Sunshine State’s beautiful coral reefs. But in Florida Bay, which sits on the west side of the Keys, many marine species have been fighting their own battle with bleaching and other effects of extreme heat, sending a strong, if silent, message about their own stress and the health of the essential habitat they inhabit.

Normally resilient creatures are struggling to survive. The record heat has not only threatened individual species — an astonishing effect on clear display in the warm South Florida waters — but the expansive and interconnected habitats, stretching from the Florida Bay to the wider Everglades and beyond.

“It’s not a grass problem, it’s not a coral problem, it’s not a sponge problem,” said Matt Bellinger, owner and operator of Bamboo Charters in the Keys. “It’s a complete ecosystem problem.”

Jerry Lorenz, the state director of research for Audubon Florida who has decades of experience in Florida Bay, likens the risks facing the estuary to playing Jenga.

“You can pull this piece, you can pull out that piece,” he said. “And you can pull out a lot more pieces. But eventually, you’re going to pull out one last piece that’s going to topple the whole thing. And that’s exactly the kind of thing we’re seeing here…”