Excerpt:

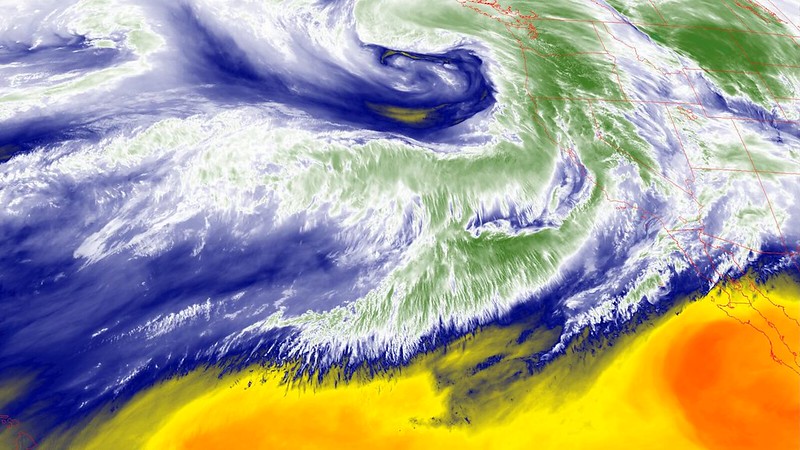

As the climate crisis supercharges storms over the Pacific, scientists are creating tools that can measure them from the inside.

The storm raged over California for more than five days. As the powerful atmospheric river made landfall, furious winds and torrential downpours ripped trees from their roots, turned streets into rivers and sent mud cascading into homes.

Along with chaos, the storm brought opportunity. Scientists were ready, on land and in-flight, to deploy instruments that measure atmospheric rivers like this one. They released tools from planes, equipped with small parachutes, or floated them up from the ground attached to balloons, directly into the storm’s path.

These small but mighty devices provide key intelligence that will help improve weather forecasts as the climate crisis makes already powerful storms more dangerous.

Atmospheric rivers have long been important features of weather systems across the US west and are vital to replenishing the state’s reservoirs and snowpack. But filled with enough moisture to rival flows at the mouth of the Mississippi – and often many times more – the strong systems that carry water across the Pacific also often cause the most destructive floods.

Warming oceans are supercharging the storms, making them deadlier and costlier. This week’s storms killed nine people, caused an estimated $11bn in damage and economic loss, and dumped half of Los Angeles’s annual rainfall on the city in a matter of days.

Now, scientists are racing to better understand these systems before they get worse. The work is greatly expanding the accuracy of weather predictions, giving water managers more time to plan and communities earlier warnings to prepare, long before overhead clouds darken, but there’s far more to learn about these systems, especially as the dangers from them grow.

Research into these airborne plumes of water vapor pulled from the tropical Pacific has grown dramatically in the three decades since “atmospheric rivers” got their name. But forecasts of where a storm will make landfall can still be off by hundreds of miles, and it’s difficult to predict how particular storms will play out.

Scientists are working to make sense of the layered and complicated conversations that happen among the ocean, the atmosphere and the land, and are hoping to gain stronger insights on how, when and where storms will strike.

“The more we learn, the more we recognize we need more data about this,” said Maike Sonnewald, the leader of the computational climate and ocean group at UC Davis.

Sonnewald, an oceanographer who uses computer science to gain insights about the climate and long-range weather forecasts, added that recent advances in the satellite age helped paint a picture of how the ocean and the atmosphere interact. That picture, metaphorically speaking, still has too few pixels.

“We don’t necessarily have a high-enough resolution to be able to model specific things,” she added, explaining that the dynamic nature of the ocean – and how easily small shifts can create big changes in the models – pose predictive challenges.

“The climate is changing – we are making the earth hotter – and that is known. It is the details that are hard to discern,” Sonnewald said. A warming atmosphere can hold exponentially more water vapor and heating ocean-surface temperatures will evaporate more quickly, so scientists can easily predict how things will worsen. It’s trickier to know when and where…