Excerpt:

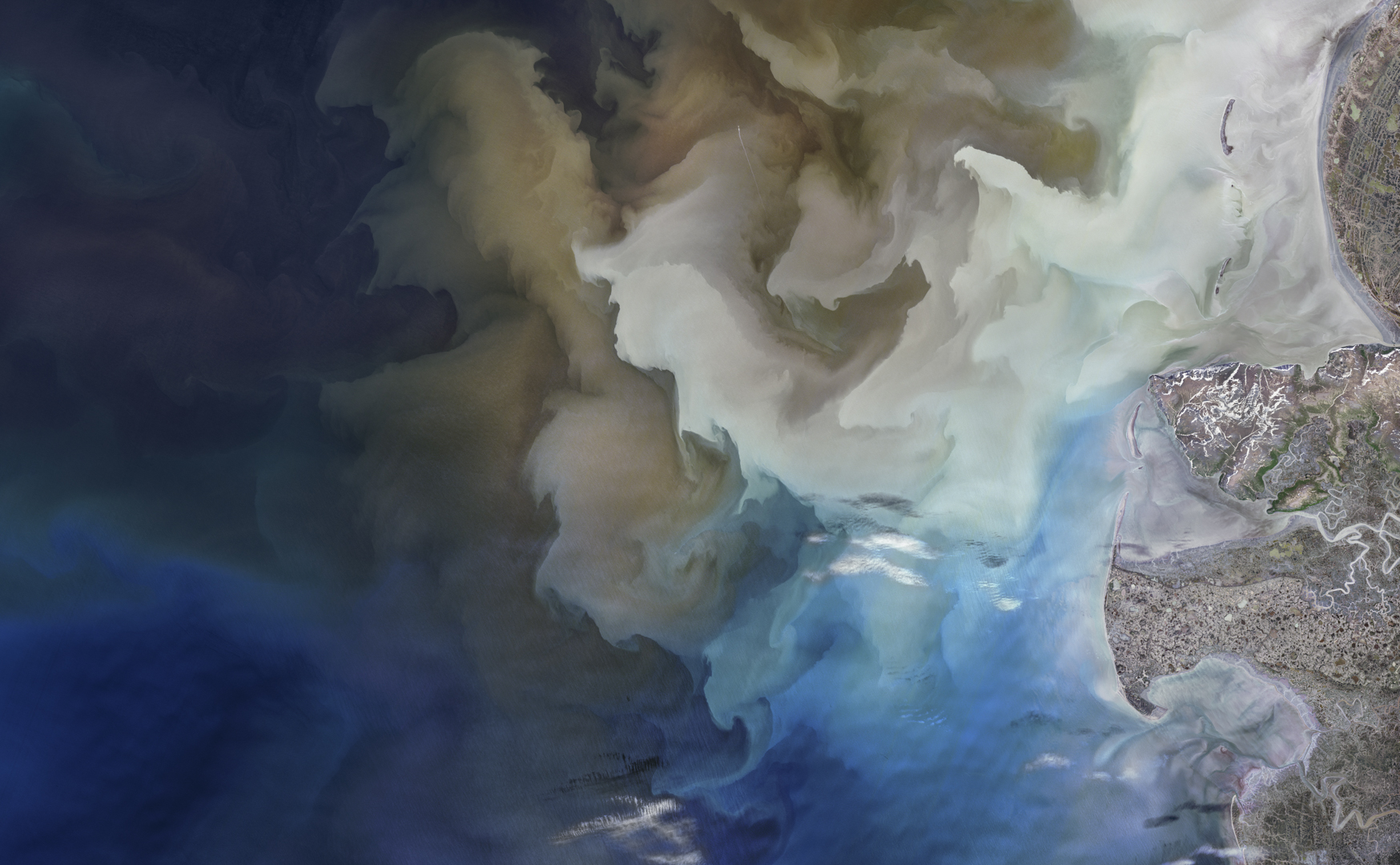

A new tool maps coastal sediments on the basis of water color. It shows that 75% of the world’s coastlines may be losing suspended sediment.

Coastlines are dynamic by nature, shaped by the push of inland sediment and the pull of ocean tides. A recent study gives a new view of coasts around the world. Researchers used changes in ocean color to show that sediment in the water has declined. That could have significant effects on everything from habitat health to coastal infrastructure.

A new tool uses Landsat, a network of land-focused satellites, to derive how much sediment is in these coastal zones on the basis of the light reflected from the water column. The tool relies on an algorithm developed by Wenxiu Teng as part of his doctoral research at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he studies remote sensing and geomorphology. Teng will present the initial findings on 12 December at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2024 in Washington, D.C.

Waves, tides, shifting sea level, river runoff, and other processes affect the amount of sediment that’s near shorelines. And the best way to track that coastal sediment is from space. High-energy coastal zones destroy most ground- or water-based instruments, making shorelines “uniquely suited to remote sensing,” said Brian Yellen, a geomorphologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and coauthor on the study. Suspended particles of fine sand, silt, and clay scatter incoming light. And the colors that result can be detected by instruments aboard satellites.

But monitoring from space has its challenges, too. Satellites that measure ocean color are generally designed to record big blobs of blue, including NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensors aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites. MODIS captures ocean color on a near-daily basis, but its 1-square-kilometer resolution is also too coarse to record small variations in a 300-meter-wide coastal zone…