Gary Griggs | 1 May 2023

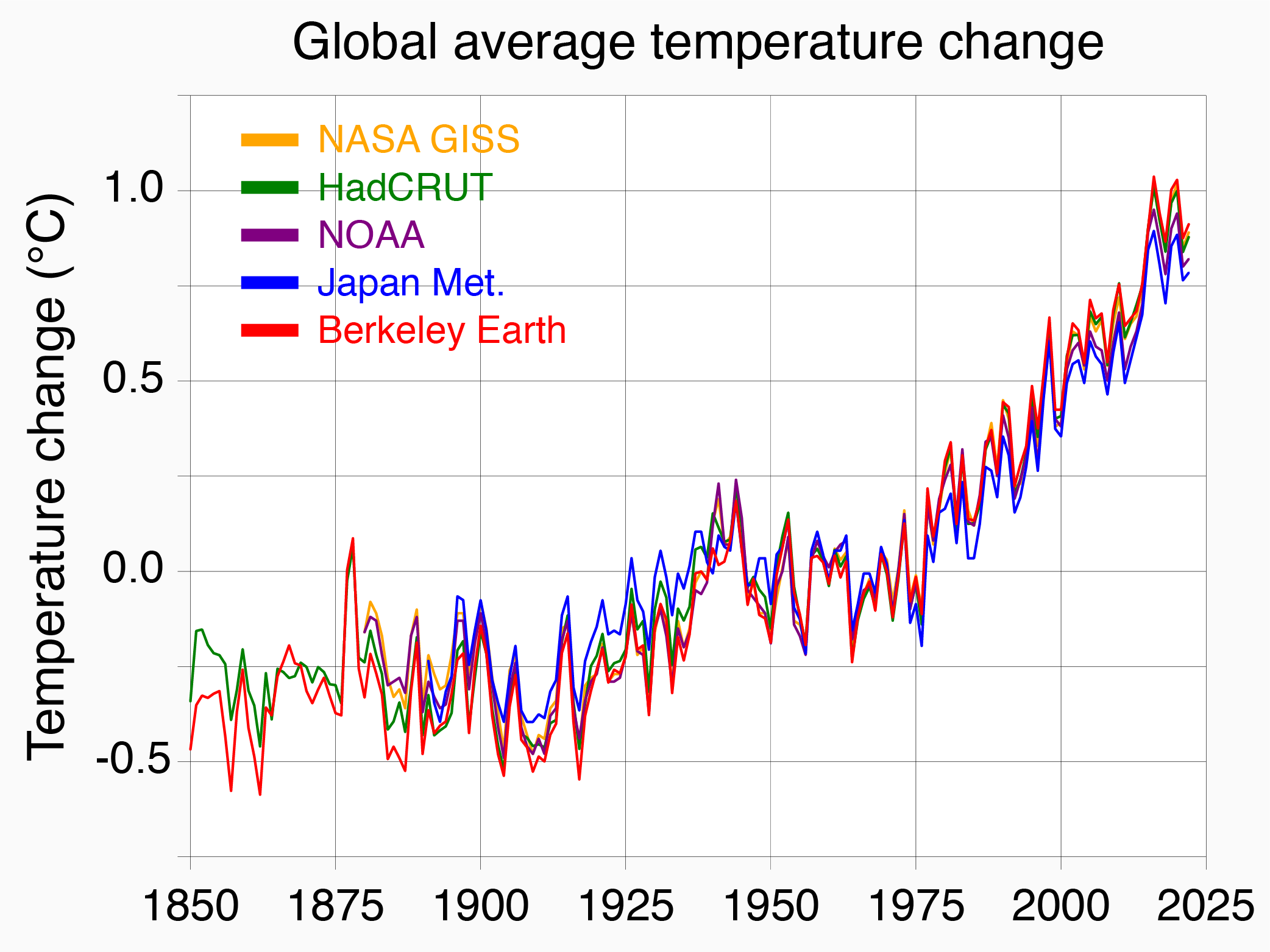

A troubling study appeared last week indicating that over the past 15 years the Earth absorbed as much heat as it had during the prior 45 years, and most of that excess energy went into warming the ocean. The continuing warming of the planet, both the continents and the oceans, may at times seem like a process that is taking place at an imperceptibly slow rate; but the rate is accelerating with increasing impacts that are more and more recognized and documented. Just because we had a winter with record snowfall in the Sierras of California, or it snows in Ohio in April, doesn’t mean that the planet isn’t continuing to warm.

The evidence is clear but it’s also important to distinguish between weather and climate. To put it simply, climate is what we predict and weather is what we get. Weather is what happens today, or tomorrow, or in the weeks or months immediately ahead. Climate is long term over decades and centuries. Both of these affect our human occupancy of the planet as well as all of the terrestrial and marine life we share the planet with.

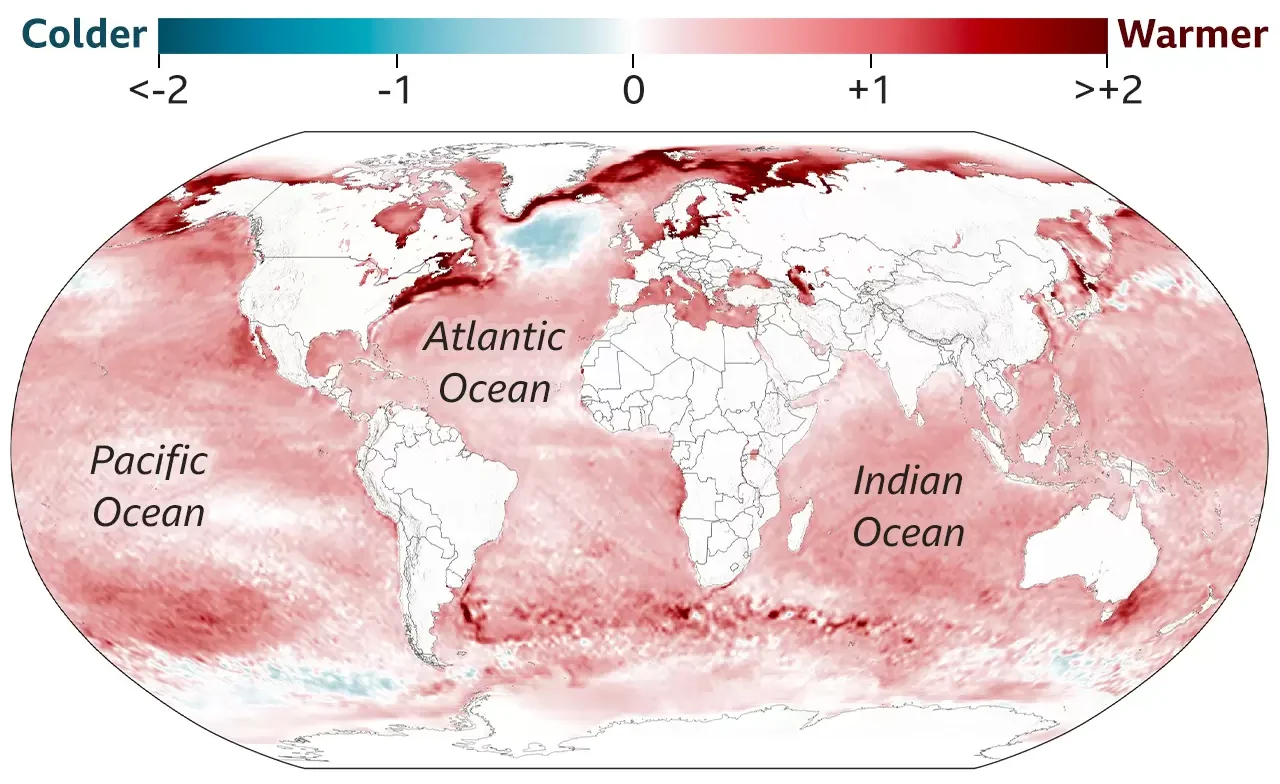

This new study (April 2023) looked at the average sea surface temperature of the world’s oceans during the 10 years from 2011-2020 compared to the 30 years from 1951-1980. With the exception of one area off the southern part of Greenland and several small areas off Antarctica, the entire ocean is one, two or more degrees C. warmer. We are continuing to heat up the oceans at a frightening rate. This is not just a scientific curiosity. The warming is having very observable impacts, and with a significant El Niño already forming in the tropical Pacific, there are going to be greater impacts ahead.

Decades of temperature records show that the higher latitude areas, particularly in the northern hemisphere are rising faster than at lower latitudes. In March of this year, the temperature of the ocean surface waters off eastern North America were up to 13.8 degrees C. (56.8 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 1981-2011 average. This is a huge difference. Overall the average surface temperature of the global oceans has increased by about 0.9 degrees C. compared to pre-industrial levels with 2/3 of that coming in the last 40 years.

One of the most pronounced and well-documented biological effects of a warming ocean is the so-called bleaching of coral reefs. Reef-building corals actually result from a symbiotic relationship between an animal (a coelenterate) and a plant (an algae). These live together with the coelenterate providing the skeleton or structure and releasing carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is used by the microscopic plant to produce organic matter and oxygen, used by the coelenterate. All coral reefs are dependent upon this interactive or mutually beneficial relationship. However, during periods or very warm water, such as during an El Niño event, the coral animal becomes stressed and ejects of casts off the symbiotic algae (known as zooxanthellae). This eliminates the built-in food source. the coelenterate then dies and the skeleton turns white. This is a dead reef and is something that happens in widespread tropical areas during El Nino events when surface temperatures rise and could become more frequent and damaging. During a strong El Niño in 2016, over half of all coral reefs faced extreme heat stress and 29% of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef died. From 2014 to 2017, 75% of the world’s coral reefs faced bleaching-level heat.

Other related effects of this increased warming of the oceans include more intense and longer duration hurricanes and cyclones as well as more frequent and severe marine heatwaves such as the northeast Pacific experienced from 2019-2021. These can have devastating ecological impacts with socioeconomic implications. Researchers believe that recent events like these would be extremely unlikely without the influence of greenhouse gas-driven warming.

On a larger global scale, ocean waters expand as they get warmer. This thermal expansion is a major driver of sea-level rise and is also a factor in the destabilization of the floating ice shelves that are holding back the glaciers and ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland. As these ice shelves collapse, which is an area of active research, and these massive glaciers flow from land into the oceans, sea level rise rates will increase markedly.

Illustration at top: Rising temperatures in the world’s oceans: Average surface temperature in 2011 – 2020 (degrees C) compared to 1951 – 1980) source: ECMWF ERA5 via BBC

(A version of this article also appears in the Santa Cruz Sentinel, 05-06-2023)