“Sand is the foundation of human construction and a fundamental ingredient in concrete, asphalt, glass and other building materials. But sand, like other natural resources, is limited and its ungoverned extraction is driving erosion, flooding, the salination of aquifers and the collapse of coastal defences…” – The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) February 2023

Older Stories that Discuss the Issues:

Forbes:

How Sand Mining Is Quietly Creating A Major Global Environmental Crisis

Vice News:

Illegal Sand Mining Is Ruining These Countries’ Ecosystems

Excerpt:

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has partnered with Kenyan spoken word poet Beatrice Kariuki to shed light on the problems associated with sand mining, part of a wider push towards a zero waste world.

“We must redouble our efforts to build a circular economy, and take rubble to build structures anew,” Kariuki says in a new video. “Because without new thinking, the sands of time will run out.”

Sand is the second-most used resource on Earth, after water. It is often dredged from rivers, dug up along coastlines and mined. The 50 billion tonnes of sand thought to be extracted for construction every year is enough to build a nine-storey wall around the planet.

A 2022 report from UNEP, titled Sand and Sustainability: 10 Strategic Recommendations to Avert a Crisis, found that sand extraction is rising about 6 per cent annually, a rate it called unsustainable. The study outlined the scale of the problem and the lack of governance, calling for sand to be “recognized as a strategic resource” and for “its extraction and use… to be rethought…”

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Additional Reading:

Our use of sand brings us “up against the wall”, says UNEP report

Sand and Sustainability: 10 Strategic Recommendations to Avert a Crisis

The role of resource extraction in a “circular” world

Excerpt:

Low risk, difficult to detect and with huge profits, this crime affects most countries in the region. There are several ‘cartels’ in this black market.

( Interntional writing with Insight Crime )

Just 50 kilometers from the famous beaches of Rio de Janeiro , one of the city’s most powerful criminals found a fortune in the sand.

Before turning himself in to authorities in December 2023, Luis Antonio da Silva Braga , alias “Zinho,” led the Bonde do Zinho militia. And beyond its criminal interests in Rio, the group had expanded into the nearby municipality of Seropédica, where it allegedly worked with a Rio de Janeiro state legislator to use floating dredges, trucks, tractors, backhoes and silos to illegally collect huge amounts of sand.

Most illegally mined sand is used in the construction sector for materials such as concrete and bricks, as well as for building foundations . It is cheaper than legally mined sand, and poor oversight by authorities across Latin America and the Caribbean has made sand trafficking a relatively profitable and low-risk activity for criminal groups across the region.

As well as filling the coffers of sometimes violent criminal groups, illegal sand mining has caused environmental damage such as the extinction of wild species, changes in river channels and increased flooding.

But this crime is difficult to prosecute, as it is often impossible to differentiate between legally and illegally extracted sand.

“ If you have a truckload of illegal sand, it looks exactly the same as a truckload of legally mined sand ,” Vince Beiser, author of a book on the history of human use of sand, explained…

Also of interest:

Q&A: How Sand Trafficking in Brazil Became a Highly Lucrative Crime – Insight Crime

Excerpt:

Brazilian authorities have launched a series of operations targeting illegal sand extraction as part of a renewed commitment to fighting environmental crimes. But much more may be required to tackle what is now a multi-billion dollar criminal enterprise.

Image at Top: Mining is removing sand from coastal sites, such as this one in Colombia, faster than natural processes can replenish it (photo © Nelson Rangel-Buitrago)

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Excerpt:

The greed for grains of sand comes at an ecological disaster and fatal human cost; murders and other associated crimes which have taken a toll on poverty-stricken communities, particularly women.

The ERC investigation, Beneath the Sands, exposes how greed for grains of sand comes at a fatal human cost: As cities rise in number and countries urbanize rapidly, sand mining-related murders and other associated crimes have taken a toll on poverty-stricken communities.

We documented sand-related crimes happening in Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Philippines and India, from tax evasion, trespassing to threats stalking activists to people caught in the crossfire between gangs known as ‘sand mafias.’

Finally, we look at how sand mining impacted the women in Cambodia, India, Kenya, and Indonesia. From home to the streets, women are on the frontlines in the resistance against these powerful sand mining operations.

Here are the stories they uncovered…

Read other articles in the series :

Women against the grain – Beneath the Sands ERC

Women in Cambodia, India, Kenya and Indonesia share how they are on the frontlines in the resistance against powerful sand mining operations in their communities.

In a trade that is dominated and driven by men, women often bear the burden of the negative social and environmental impacts from sand mining activities across the world. This is evident in much of our reporting on the global industry. As is common with many environmental issues we face today, we feel that the disproportionate burden to women is a heavily underreported issue…

We can’t run away – Beneath the Sands ERC

The rise in sand demand endangers the lives of children, laborers, journalists and environmental defenders.

Greed over grains of sand has a fatal human cost: As cities rise and countries urbanize, sand-related murders and other associated crimes have taken a toll on poverty-stricken communities.

In parts of the globe, where sand is extracted, criminal gangs and sand mafias control the multi-billion dollar trade, spawning violence in land-rich, developing nations. On their trail are hundreds of people — miners, journalists and environmental defenders — reported to have been killed, imprisoned or threatened…

Reclamation: A flawed solution – Beneath the Sands ERC

A deep dive into the rationale behind some of Asia’s reclamation projects, the toll they take on our environment and communities, and the search for more sustainable alternatives.

Reclamation is seen as a solution for countries to deal with increasing land demands, by expanding their territory and rehabilitating previously uninhabitable lands or seas. Yet, the process guzzles an alarming amount of sand, causing massive environmental damage as well as a rise of transnational criminal syndicates trading in illegal sand..

Nowhere to fish, nowhere to farm – Beneath the Sands ERC

Across Asia and Africa, countries are dealing with massive sand mining that destroys fishing grounds, farmlands, and homes.

Beting Aceh, an island in Riau Province, Indonesia, has been Eryanto’s home for 40 years. The island is known for its white sandy beaches and clean ocean water; more than half its residents are fishers.

But the island has drastically changed over the past two years. The ocean water is getting murky, the beach is shrinking, and it has suffered from massive erosion, indicated by the uprooted trees strewn along the coast. Many villagers say the damage is linked to a sand mining operation happening between Beting Aceh and the neighboring Babi Island…

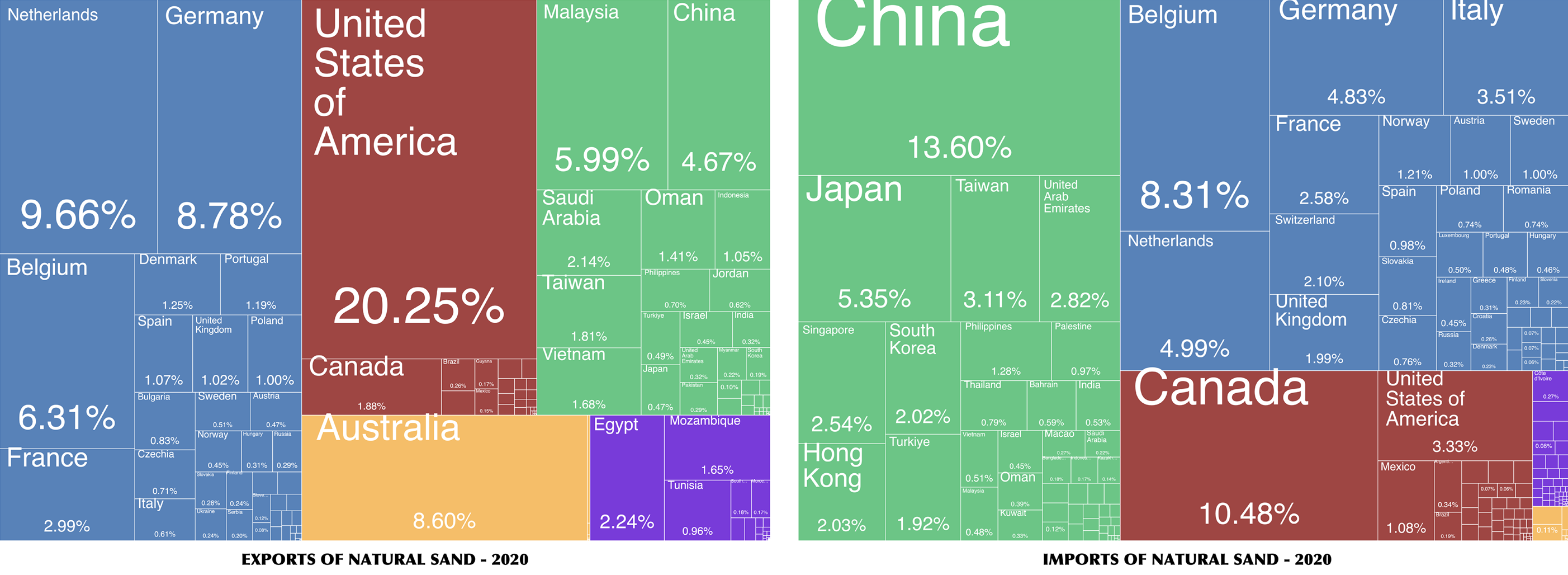

Global sand trade figures don’t add up – Beneath the Sands ERC

On March 17, more than 120 tons of sand packed into drums was loaded onto the Basle Express, a container freight ship more than three soccer fields long. The ship was docked in one of America’s major ports, Savannah, Georgia, in the Southeast region of the country.

The shipment itself was not remarkable — except for how it is emblematic of the international sand trade, highlighting the type of sand that attracts foreign buyers, the countries that are buying and those that are selling…