Excerpt:

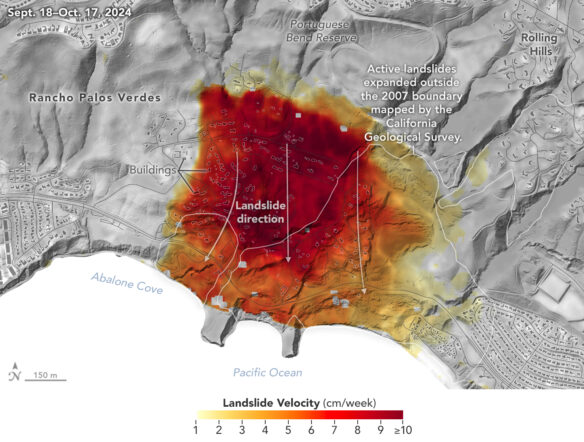

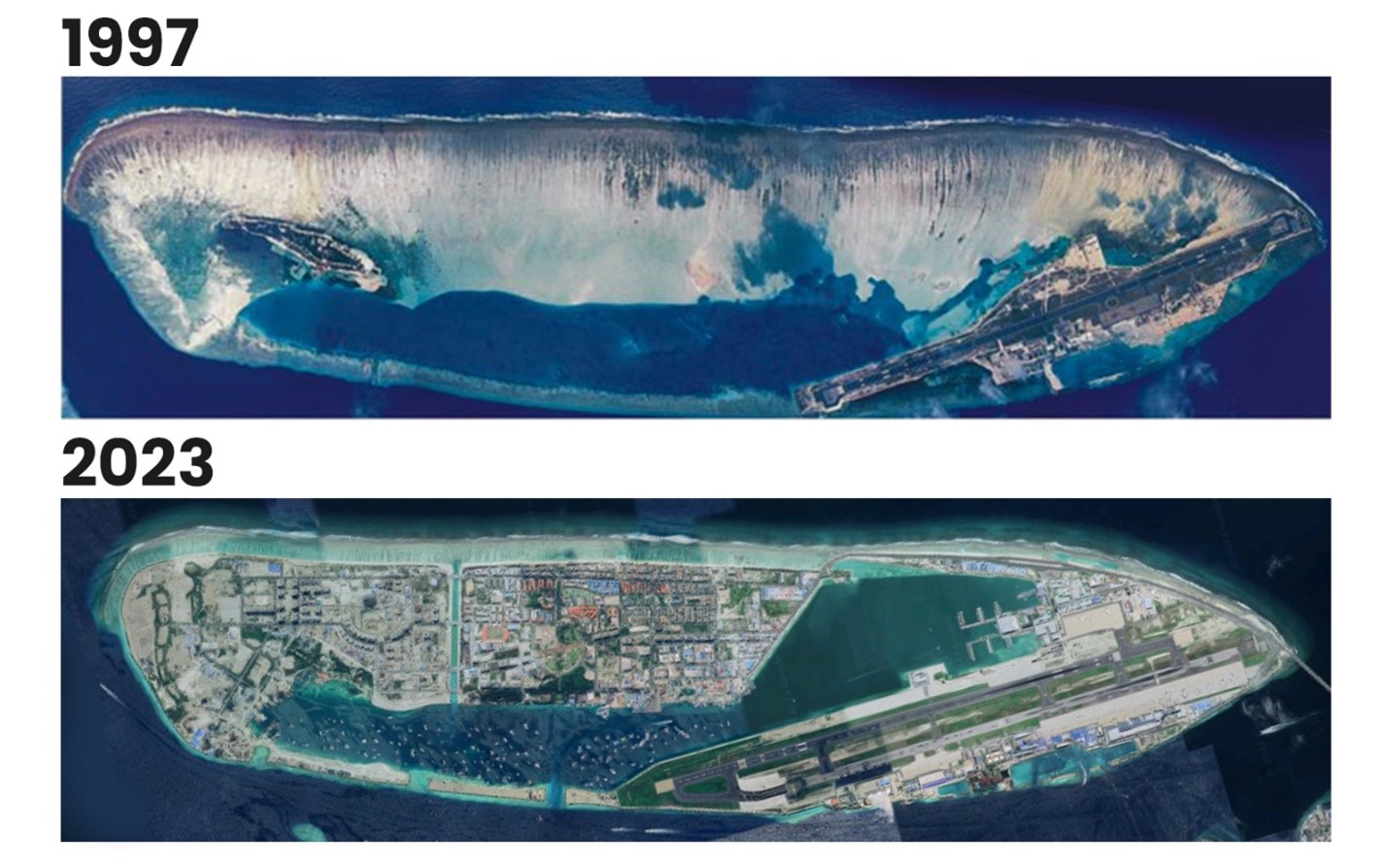

The island nation is expanding its territory by dredging up sediment from the ocean floor. . . But scientists, former government officials and activists say such reclamation can harm marine ecosystems and make the country more vulnerable to rising seas.

Sun, sand and sea.” Those are the three ingredients for tourism in the Maldives, Mohamed Shaiz’s father told him. For more than a decade, Shaiz’s family owned a successful local hotel in Addu, the Maldives’ southernmost atoll. But nearly 9 months ago, the government took away the sea.

A state-sponsored project had pulled up sediment from offshore areas and used it to extend the beach in front of the hotel by 130 metres — too far to walk for most tourists who want easy access to the ocean. Now all Shaiz sees from his hotel is a human-made desert and a slew of cancelled reservations.

The Maldives is an 820-kilometre-long chain of nearly 1,200 islands dotting the Indian Ocean. The nation has become one of the most popular luxury tourism destinations in the world because of its Instagrammable beaches and its advertising slogan: “the sunny side of life”. But the Maldives is also one of the countries most vulnerable to sea-level rise. With 80% of its land less than one metre above sea level, some scientists predict that the islands could be completely submerged by 2100.

In an effort to keep the country above water and thriving, the government is adopting a strategy used by many nations around the globe: land reclamation. The sandy stretch in front of Shaiz’s hotel is some of the newest land on the planet, dug up from the bottom of the ocean, sucked through pipes and piled along the coast to make more space.

Maldivian government officials say that the land is necessary to make room for economic development, especially as sea levels rise.

“This will be a doorstep, a job destination and an income-generating destination,” said President Mohamed Muizzu at the inauguration of a new land-reclamation project last December.

Critics are unconvinced, and say that the country has enough space to thrive. One swathe of land on a neighbouring island near Shaiz’s hotel was reclaimed in 2016. It remains undeveloped today. “Call me in five years,” Shaiz says, gesturing to the newly created desert in front of his hotel. “This land will be the same.”

In addition to the disputed economics, there is serious concern about the environmental damage that land reclamation can cause. Studies in the Maldives and at other sites around the world have shown that it can harm corals and seagrass, damage natural barriers, such as sand bars, mangroves and estuaries, and destroy marine habitats. “Atolls are extremely vulnerable ecosystems,” says Bregje van Wesenbeeck, the scientific director of Deltares, a Dutch research institute for water management in Delft. “Once you start to interfere with them, you’re sort of failing them…”

nature video – (04-24-2024):

Should the Maldives be creating new land?

As climate change leads to sea level rise, low-lying island nations like the Maldives are facing an existential threat. One solution is to ‘reclaim’ land by relocating sediment from the ocean floor. This can provide more space for development and increase resilience to rising oceans. But many are concerned about the environmental and social impacts of such projects. In this film we explore the process, the impacts and the uncertainties around this race to adapt.

Additional Reading . . .

The Maldives Is Racing To Create New Land. Why Are So Many People Concerned? – Nature

Sun, sand and sea.” Those are the three ingredients for tourism in the Maldives, Mohamed Shaiz’s father told him. For more than a decade, Shaiz’s family owned a successful local hotel in Addu, the Maldives’ southernmost atoll. But nearly 9 months ago, the government took away the sea…

Behind the Story: Land Reclamation in the Maldives – the Pulitzer Center

Most visitors come to the Maldives for its resorts and pristine beaches. For Pulitzer Center grantee Jesse Chase-Lubitz, there’s a story behind that sand…The Maldives face an existential threat from sea level rise, and rebuilding the coastline with dredged sand has become a popular solution. But a series of activists on the 1,200-island archipelago are questioning the tradeoffs…Through interviews with taxi drivers, hotel owners, politicians, and scientists, Chase-Lubitz found that land reclamation is not a one-size-fits-all policy…

How Saving The Maldives May Actually Destroy It – the Medium

Just imagine waking up one day to find the sea that was once at your doorstep replaced by a fake 130-meter beach. This is the new reality for the residents of Addu, the southernmost atoll of the Maldives. But this shocking transformation isn’t new — it’s a desperate move to keep the country above water and thriving…

Maldives to battle rising seas by building fortress islands – PHYS.ORG

Rising sea levels threaten to swamp the Maldives and the Indian Ocean archipelago is already out of drinking water, but the new president says he has scrapped plans to relocate citizens. Instead, President Mohamed Muizzu promises the low-lying nation will beat back the waves through ambitious land reclamation and building islands higher—policies, however, that environmental and rights groups warn could even exacerbate flooding risks…

Satellite Image Shows Construction of World’s First Floating City – Newsweek

A floating city, considered the world’s first, is starting to take shape in the turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean…Satellite imagery provided exclusively to Newsweek by Maxar Technologies shows the state of construction of the Maldives Floating City, a development of modular floating platforms that is scheduled to be completed in 2027….

Why Time Is Running Out Across the Maldives’ Lovely Little Islands – the New York Times

Global tourism brought a modern economy to the country’s thousand islands. For many Maldivians, the teeming capital beckons…

Additional Resources and Media . . .

Government of Maldives (07-18-2023):

Addu City’s Land Reclamation plan

Forbes (07 -14-2022):

The World’s First Floating City In The Maldives

Conrad Richardson (01 -28-2023):

How the MALDIVES plans to survive SEA LEVEL RISE