Sea Turtle Egg Poaching Legalized in Costa Rica: The Debate

By Claire Le Guern

Two decades on, an unusual project to stabilize the population of Olive Ridley sea turtles in the coastal town of Ostional on Costa Rica’s Nicoya Peninsula that led the Government to legally permit an exemption to the ban on harvesting sea turtle eggs, remains controversial.

The rationale for circumventing a global conservation effort is to sustainably maintain the local population of Olive Ridley sea turtle, while concurrently providing a consistent income stream for the economically challenged local community of Ostional who may harvest the turtle eggs from the beach to sell locally.

People on both sides of this contentious issue have observed that with this project the government of Costa Rica has in essence legalized poaching. Indeed, despite the vigorous defense of what is claimed to be a well-managed and officially sanctioned harvest by needy local people, critics abound. Even after twenty years, independent turtle authorities remain far from any universal agreement as to the scientific and economical basis for this project’s mission and its impact.

Four of the world’s seven species of marine turtles nest on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica, the Pacific Green (Chelonia Mydas) or “Negra,” Leatherback (Dermochelys Coriacea) or “Baula” or “Canal,” Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) or “Carey,” and the Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys Olivacea) or “Lora” or “Carpintera.” Olive ridleys get their name from the coloring of their heart-shaped shell, which starts out gray but becomes olive green once the turtles are adults. Forty-seven beaches on the Pacific coast have been identified as having turtle nesting activity.

The Olive Ridley turtles have been around a very long time, more than 100,000,000 years, are naturally very prolific and the most numerous of the seven existing species, with breeding beaches throughout the tropics, though it has, until recently, been considered “Endangered.” Indeed, past global numbers may have been as high as 10 million populations, yet the Ridley populations had declined by more than 50% from 1950’s levels. A single generation of men accomplished, prior to the subsequent laws protecting sea turtles and their eggs, what had seemed impossible: extensive fisheries and eggs harvesting in the early 20th century nearly wiping out in the blink of an eye what had taken a hundred million generations to create.

As a result of bans on fisheries and legal protection, the Olive Ridley turtle is nowadays, classified as “Vulnerable,” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature And Natural Resources (IUCN), and is listed in Appendix I of The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

For 10 months of the year, usually around the third quarter of the moon, olive Ridleys swim by the hundreds of thousands to an 8 kilometers long by 200 meters wide beach, at Ostional, in an ancient reproductive rite little understood by scientists, called arribadas (literally meaning “arrivals” in Spanish).

Arribada, on Playa Ostional, Costa Rica. Photo Source: Dave Sherwood

Arribada nesting (massive turtle nesting and egg laying) is a behavior found only in the genus Lepidochelys, Olive Ridley Turtle. Uniquely among marine turtle species, which more normally nest individually, Ridleys congregate en masse at sea and then swarm the beaches like battalions. Although other turtles have been documented nesting in groups, no other turtles, marine or otherwise, have been observed nesting in such mass numbers and synchrony.

In such a strategy, simultaneous mass nesting is nature’s way of ensuring that natural predators, turkey vultures, feral dogs and raccoons, may be “overwhelmed,” having eaten all the fresh turtle eggs they want, and yet sufficient numbers of eggs are left over to produce a sustainable population of Olive Ridleys, maintaining the species.

The most important nesting beach on the Pacific coast is at Ostional, situated in the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge (Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Ostional).

At Ostional, the arribadas occur on a lunar cycle of approximately 28 days. The majority takes place around the last quarter of the cycle although this event may happen at any time including the full moon and two arribadas (first and last quarter) may occur in the same month. The size and duration of the arribadas varies between the dry and wet seasons. Those occurring in the dry season of January to April tend to be smaller (approximately 5,000 turtles) and of shorter duration (less than four days). In the wet season of May to December, up to 300,000 turtles may lay over a period of eight to 10 days. On a number of occasions between August and October, two arribadas of 10 days each, have occurred in the same month. This results in continuous activity during the month with a few days of lower activity and two peaks of maximum nesting.

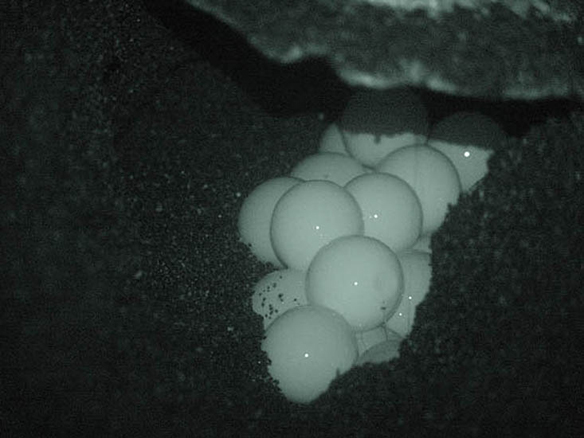

Females nest every year, once or twice a season, laying clutches of approximately 100 eggs. The turtles generally ride in on the high tide at night but during an arribada they start arriving around 4 p.m. and keep coming until 7 a.m. the next morning. Used to a life in the ocean, the turtles painfully drag their heavy bodies over the beach until they get above the high tide line. There, flicking clouds of sand, they dig a hole with their flippers and drop in an average of 100 leathery, white eggs the size of ping-pong balls. Over the course of the arribada nesting, females may leave as many as 10 million eggs in the black, volcanic sand of Ostional beach.

Ostional is one of two dozen beaches in the world where the Olive Ridley’s arribadas nesting occur. Arribadas take place on a few beaches in the eastern Pacific and northern Indian oceans. In the eastern Pacific, besides Costa Rica, arribadas occur from June through December on beaches on the coasts of Mexico, Nicaragua, and on a single beach in Panama. In the northern Indian Ocean, arribadas occur on three different beaches along the coast of India. Solitary nesting occurs extensively throughout this species’ range, and has been documented in approximately 40 countries worldwide. (NOAA).

The largest arribada thus far recorded in Ostional, took place in November 1995 when a calculated 500 000 females came ashore.

Arribadas’ downside is that the oncoming and succeeding flows of turtles, arriving on a same surface in such quantity in such a small time frame, lead to excavation of each others’ previously sand buried eggs. Indeed, as many as 200,000 Ridleys may pile ashore with as many as 20,000 at a time, digging their nests at Ostional during the course of three or four nights. Many, if not most, of the nests buried on the first and second night get dug up again on subsequent nights by later arrivals, causing destruction not only to those eggs, but, due to bacterial decomposition of the broken eggs, gross contamination of the surrounding sand. As a result, arribada beaches often realize a very small (1-2%) hatch success.

Photo Source: Dave Sherwood

In the early 1980s, biologists from the University of Costa Rica (UCR) concluded that, because of limited space on Ostional beach, the succeeding waves of nesting females coming ashore during these arribadas destroyed, and/or contaminated 70-90% of the previously laid eggs. Researchers, along with the Environmental Ministry, thus concluded that there would be no harm to the species’ relative abundance along Costa Rican shores if, instead of being trampled into one big scrambled mess, Ostional community members were permitted to dig up 1% of the nests and consume/sell the eggs.

Scientists figured that by removing eggs laid during the first two nights, the rate of successful hatching and hatchling survival might increase. The researchers wondered: why not let poachers have the doomed eggs?

Thus was born an experiment unique to Ostional. Elsewhere throughout Costa Rica, taking marine turtle eggs is illegal, and has been since 1966.

“What we have done is turn people into predators,” says Dr. Anny Chavez, a sea turtle biologist and one of the founders of the Ostional project, which is world famous among turtle activists.

An exception to the international ban on turtle eggs collecting was granted and the Ostional community was legally permitted to harvest a specific amount of eggs for commercial purposes under the supervision of the Ostional Internal Development Association (ADIO in Spanish).

Ostional community, approved in 1990 by executive order N° 28203-MINAE-MAG, law N° 8325 of the Protection, Conservation, and Recovery of Sea Turtle populations enacted on November 28th, 2002 and by law N° 8436 of Fishing and Agriculture on April 25th, 2005.

The government of Costa Rica allows then, on an annual, temporary suspension of the ban on turtle-egg taking, that the people of Ostional harvest, through an egg-harvesting cooperative, the doomed eggs on the first two dawns of an arribada.

The egg harvest at Ostional is regulated and legal.

A formal co-management model between the University of Costa Rica, a community organization called ADIO, and the Ministry of Natural Resources (MINAET) in Costa Rica, was installed to regulate the program.

Every 5 years the program is reviewed and the egg harvest management plan is reviewed and updated as needed, then submitted to the Government for approval.

The current plan notes that:

a. The current density of nests is 11 nests per square meter (Olive Ridleys can only sustain about two

nests per meter without impacting hatchling emergence success).

b. During the arribadas, the females dig up the nests of previous nesting events.

c. Due to the high level of egg breakage, putrefaction rates are very high and the resulting high levels of fungus and bacteria contaminate 100% of nests, reducing emergence success. Removal of surplus eggs has help the population increasing the hatch success by 5%.

d. Eggs can only be harvested during the first 36 hours of an arribada.

f. To be declared an “arribada”, more than 80 adult females must be nesting simultaneously.

The egg harvest program employs 300 local people and the gross income from the program is about $150,000 USD. About 15% of the eggs are harvested. While there are constant concerns about the balance between maintaining the community’s desire and tradition to harvest and consume (or sell) the eggs and the need to protect this precious resource on balance, the program is viewed by some as an example of pragmatic conservation.

Ostional, black sand beach. Photo Source: Lara Napeleona

No harvesting of the late eggs is allowed. They are protected as they incubate and the hatchlings emerge to return to the sea.

The harvested eggs are then distributed and sold throughout Costa Rica at a government regulated low price, half the price of a chicken egg. Only eggs stamped with the ADIO trademark may legally be sold, packed in sealed bags displaying the association’s logo and sold with corresponding invoices, and purchased in Costa Rica.

This has been believed by some, to have had a dramatic effect on the strong black market. The strategy initially was to attempt to flood the markets with turtle eggs easily and cheaply available, letting some think that it is no longer worthwhile for people to sneak onto beaches in the middle of the night to dig up a few eggs.

In return, the Ostional egg harvest management program advocates that the community must clean debris from the beaches, patrol day and night for poachers and protect the turtles and their eggs.

Forty-five to fifty-four days after they eggs have been laid, the hatchlings emerge, depending on incubation temperatures, which will also determine if they will become male or female. As soon as the hatchlings have struggled out of the sand, the race to the ocean begins, under Ostional community’ s requested careful supervision.

With eyes barely opened, the mini turtles smell the breeze and instantly know the right direction. The small turtles need the run to develop their lungs. Most hatchlings don’t reach maturity, but those who make it will remember the smell of their beach. After 10 – 15 years they will return to their place of birth and again lay their eggs into the black sand of Ostional.

The result?

Bacteria have been allegedly reduced on Ostional beach. More eggs are maturing to hatching on this beach. More hatchlings are being born from this arribada nesting location. The population of Ridleys has increased to the point where they are now coming ashore, at more and more beaches along Costa Rica’s coast.

Despite the vigorous defense of what is claimed to be a well-managed and officially-sanctioned harvest by needy local people, independent turtle authorities are not universally in agreement as to the scientific basis for the activity and its impact, and critics abound regarding the very key-stone of this program. Controlling nature’s way by creating a legal exemption to an international ban on collecting turtle eggs, even though perfectly well intended, indubitably goes against the belief that real sustainability is best obtained by protecting nature, via well-thought legal frames indeed, but ones that ultimately should not infringe in the always efficacious by essence and natural, evolutionary patterns.

Furthermore, some argue that Ostional exception has not only seeded egg poaching as a vocation but also sprouted an ever-flourishing black market, locally and overseas. Mostly to blame is the absence of de facto regular and efficient control of the chain of custody between the harvesters up through the consumers. Derogatory status to existing law should not be allowed, specifically when the law itself cannot be enforced, which is a widely recognized problem in this matter.

As reported by Dennis Rogers writer in AM Costa Rica Newspaper (October 26th, 2010 article), the Sea Turtle Conservancy’s, (founded by Archie Carr as the Caribbean Conservation Corp.) official position on the Ostional situation is “While we don’t agree with this egg collection, the project is endorsed by the Costa Rican government for the time being,” according to Rocío Johnson, public relations coordinator.

The main objection of critics is that the existence of Ostional eggs on the market provides cover and even encouragement for poaching of the same, and other species, on non-protected beaches around the country. This species is the most abundant off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and nesting takes place along the whole length of the country on 48 of the 51 beaches identified as suitable for this activity. As a matter of fact, all other sea turtles that nest in Costa Rica are actually in a far more perilous state than the Olive Ridley.

On the Costa Rican beaches where solitary nesting takes place, it is estimated that human egg poaching results in the destruction of between 80 and 100 percent of the nests, depending on the accessibility of the beach. The Nosara beach for instance, located to the south of Ostional, is occasionally used during the large arribadas by the same nesters of Ostional. The nesting population, where solitary nesting is concerned, has been estimated at between 4,500 and 5,000 individuals.

After nesting, the turtles migrate to deeper waters while staying relatively close to the coast and spending a large proportion of the time on the surface. Following the primary dietary source of shrimp, coastal migration takes place between Mexico and Chile. However, there does appear to be a resident population along the Costa Rican coast.

Furthermore, until a few years ago, arribadas nesting were known to occur only at Playa Nancite, off-limits to visitors, and Playa Ostional, in Nicoya. The scarcity of available space on Ostional beach was the main scientific reason as to install a legalized harvesting of eggs for a limited time on a limited space, this because of the occurrence of arribadas deemed too large for the “small” beach. This was the keystone of the Ostional project. Ostional is 8 kilometers long, 200 meters wide beach. One might argue that eight kilometers is quite a long stretch of sand… But more importantly in the debate, recently Olive Ridleys’ arribadas have occurred at other Costa Rican beaches, such as Playa Guiones (Nosara) and Playa Camaronal, further south, and needless to emphasize that they are obviously not regulated and protected as Ostional is.

Photo Source: Dave Sherwood

What is often described as an ancient arribada ritual occurring at Ostional actually has been recorded only since 1959 when the first noticed large-scale arrival of Olive Ridley turtles occurred. Similar phenomena were known in Mexico and elsewhere before that. The Costa Rica events at Ostional and the smaller Nancite beach in Guanacaste did not even come to the attention of the scientific community until 1970. This is very little time to monitor populations of a long-lived species.

Supporters of Ostional’s arribadas’ outcome experimental project, say that the eggs destroyed by late-arriving turtles rot and promote pathogens that will damage the incubating eggs and their contents. These claims are currently under scientific investigation. Independent biologists have formed the Costa Rican National Sea Turtle Conservation Network to look at this question.

All turtles are still principally threatened by incidental capture in shrimp nets, on the long-lines off the coast and the illegal poaching of the eggs. Along the Pacific and Caribbean coasts, turtle meat has traditionally been used as an ingredient in traditional dishes and turtle shells are often carved into jewelry. Turtle meat and eggs are a delicacy and a way of life in many countries, including Costa Rica evidently.

Titled “Underwater Sadness,” a photograph of a caretta sea turtle caught in a net in the Sea of Cortés. Photo Source: Ramón Domínguez

Costa Rica outlawed the taking of turtle eggs nationwide in 1966. The Law for the Protection, Conservation and Recuperation of the Marine Turtle Population (Law 8325), established in 2002 and designed to help protect declining sea turtle numbers, mandates three years of prison for anyone who “kills, hunts, captures, decapitates, or disturbs marine turtles.” The same law also imposes three months to two years of jail time for “those who detain marine turtles with the intention of marketing or commercializing products made from marine turtles.”

Nowadays, despite the legal interdictions, hundreds of locals do consistently gather at remote Costa Rican beaches, with no enforcement forces there…nobody to patrol the miles-long stretch of sandy beaches.

According to Sea Turtle Restoration, poaching on any Central American turtle beaches, and perhaps the world, is close to 100%. Even the protected areas like Ostional, poaching in the Guanacaste region is estimated at 95%.

As recall “Chevy,” a Costa Rican man interviewed in an article published in the Tico Times Directory (Costa Rica Poaching of Costa Rica Sea Turtles Eggs- Turtle Poll ):

” In the late 1960s, during the incredible arribadas massive pack trains of horses and donkeys carried away hundreds of millions of eggs collected by the hueveros (egg poachers), and at each nesting season. “Chevy” recalls that many Costa Ricans, leaving on the coast, remember the time when they were young, being sent to the beach by their parents, with sisters and brothers, to get sea turtle eggs. They would come back with baskets filled, within fifteen to thirty minutes. When money was needed, they would fill up a bunch more of baskets and sell them to local markets, restaurants and street vendors. “Back in those days one dollar was worth around 6-7 colons. Dozen eggs would be sold between 3 to four colones.

Nobody thought about conservation back then, but since the mid 1970s times have changed for the sea turtle. With worldwide eco-protection and tight legal frames, the demand for turtle and its eggs has increased, to some say, “epidemic poaching!”

Turtle meat, deemed to be ” an awesome tasting seafood” and eggs are indubitably, not only a delicacy, but also a way of life. Poaching of nests nation wide, has been a constant problem due to a traditional demand and taste for eggs for baking and as supposedly aphrodisiacal drinks in bars and brothels. The eggs are richer tasting than chicken eggs and packed in protein. Today, turtle eggs are found in local bars, restaurants and markets that are off the beaten path, far from most tourist areas. And during the nesting season, roadside stands offer them by the bucket full for $2 per egg.

As reported in The New York Times: “In a country where turtle eggs are traditionally slurped in bars from a shot glass, uncooked and mixed with salsa and lemon, biologists are also promoting cultural change. “Of course 25 years ago, you went out with your friends or family and dug up the eggs,” said Héctor García, 42. “It is a tradition. They are delicious, cooked or raw.” Today egg collecting is illegal in Costa Rica, but poaching is still common in many towns.”

“It is common street talk that turtle sanctuaries have made deals with commercial poachers who sell to traffickers. They give them X amount of eggs; in return the poachers will not steal or just plain old fashion bribery and extortion. Egg collecting and selling is illegal unless you have a permit; to get around this, these sanctuaries give the poachers a receipt, so in fact they can “legally” resell those eggs to “whomever” they please.” (Excerpt from the Tico Times Directory). Further reporting:

“When I asked Chevy about the law, he laughed, “¿Qué ley” (What law?) and explained, a few weeks ago a few of his friends were caught with a few thousand turtle eggs. His friends ended up splitting the shipment with the two officers.”

Today, there is nothing wrong de facto, with having a few turtle eggs in your possession, and normally if caught with a bunch, your fine is to share those eggs with the policeman.

There is no real regulatory enforcement and/or authority to competently oversee the number of eggs sold and collected due to lack of funds, resources, and manpower. The legal sale of any turtle eggs in the country has opened the door for the clandestine eggs harvesting from other beaches, undoubtedly. The Ostional exception has seeded egg poaching as a vocation and sprouted a flourishing black market, locally and overseas.

The local black market supposedly ” flooded” by cheaper prices, has not stopped nor hindered the demand, which not only remains strong, but the tradition and taste for the eggs is somewhat perpetrated, if not intensified or encouraged, by timely offering legal turtle eggs, at cheaper price.

This program has reportedly greatly increased the population of the Olive Ridley turtle at the site. Greater population, means more eggs available, and as we mentioned earlier, arribadas are not only seen on protected Ostional beach anymore, but witnessed elsewhere, as well as solitary nesting’s, present and striving all along the Costa Rican coast. So many turtle eggs, so easily located, so much money to be made.

The demand for black-marketed turtle eggs has inflated local sales by 500% (according to the Costa Rican Conservation network).

To the program’s defense, it has been argued that Costa Rica’s law providing the Ostional exception is mainly geared toward the locals because of cultural habits and economic disarray. The egg take was intended to provide a fledgling coastal community with a regulated source of income and food. Generation after generation has used simple turtle eggs to feed their families, directly or by the commercialization of the eggs. The exception to the law was put in place as a way to sustainably manage the area’s nesting turtle population; however, with no way to enforce that only Ostional eggs are commercialized, Costa Rica has opened the door to “a kind of sea turtle egg consumption pandemonium.” (AM Costa Rica News).

The question indeed arises: practically are the eggs going exclusively to the local economy as first intended, or to the oversea ones?

With the increase of worldwide conservation, it has been noticed that the largest demand for turtle eggs is for their supposed aphrodisiac effects, just like rhinoceros’ horns or shark fins. The largest market is in the Asian countries. In regards to the black market specifically, it appeared that the problem is not mainly Costa Rica’s culture and tradition, but extends to meet the greed of the Asian market for that matter. The demand for turtle eggs is reported to range between $100-$300 USD per egg. It is easy to see how the local smugglers have added turtle eggs to their list. The market can be profitable as drug smuggling, but nowhere close to the high risk. Due to lack of funds, resources, and manpower, literally millions of eggs find their way overseas.

Turtle Eggs for Sale, 30e San Jose, Avenida Central, Paseo Colon, Costa Rica. Captions and Photo source: ©© Kansas Sebastian

As the Tico Times Directory reporter, asked “Chevy”:

“How widespread is the overseas poaching?” He smiled back, “It’s like a strong wind, you can’t see it, but you can sure as hell feel and see the effects of it.”

Locally, with no transparency in the turtle egg business, the legal loophole opens the floodgates for almost anyone to claim their eggs are from Ostional, thus leading to the rampant poaching of all types of sea turtle eggs on both coasts.

“Who’s goin’ to question, “What beach do the turtle eggs come from? And “If the eggs were legally or illegally harvested?”

Nobody knows how many bags of eggs have found their way to the black market, locally and overseas. In other words, a lot of bags are stamped to resemble the Ostional stamp of approval, but no one checks to see if it is the stamp is real or just a forgery.

As reported by Dennis Rogers, AM Costa Rica News, internal conflicts and discrepancies exist within the program and organization. The Ostional Development Association’s 2008 report for instance, allegedly gives detailed accounting of the number of eggs harvested that year on Ostional beach, and the various uses by the community of the money remaining after the membership’s 70 percent share is doled out. Yet, conspicuously absent, is any discussion of the actual number of turtles that came that year. Accurate monitoring of the eight kilometers of nesting beach would require carefully designed techniques during a large wave of turtles, many of which lay at night. It is not happening.

The right to harvest turtle eggs is restricted to the 260 members of the association, registered as a cooperative. Membership is not automatic and different numbers of individuals in the same families are included. This results in some households getting a larger share than others, and this apparently is a cause of friction.

Furthermore, Ostional has been engulfed in nasty, small-town feud between the egg-harvesting cooperative and the resident biologists, over the misuse, respectively, of turtle-egg income and scientific spoils (reports John Burnett, NPR). The conflict broke out when the husband-and-wife team, biologist Anny Chavez and Leslie du Toit, a South African sea turtle enthusiast, began building a small hotel at the research station on the edge of town where they live. The couple wants to begin charging students and researchers for lodging and lab space. The community is angry that the two are starting a business on public land; other Costa Rican biologists have also questioned the ethics of the enterprise. Cooperative directors allegedly receive kickbacks from egg retailers and pocket the additional profits. “They’re a mafia; We found out what was happening and told the authorities. Our complaints alienated us.” For their part, the egg harvesters clearly do not like the couple watching over their shoulder.” say locals. Anny Chavez, who helped found the egg-harvest plan, wonders, in retrospect, whether the conflicts could have been avoided.

The experiment’s designers were biologists who apparently thought they understood turtles better than they understood people. “When we started the project, we were worried about the biological basis. We didn’t work hard to try and train the community about how to manage this big amount of money. And for me, this is part of our fault,” she says.

Confronted to a cultural and economical dilemma, when attempting to install a satisfying system to save turtles and their eggs while taking in consideration needs from a coastal population economically challenged, finding a sustainable and efficient path to resolve the conflict is a difficult task.

Aware of the cultural tradition of poaching, Mark Ward, founder of Sea Turtles for Ever (STF), an Oregon based non-profit whose sea turtle conservation work includes actively patrolling the Punta Pargos nesting beaches on Costa Rica’s Pacific coast, offers hueveros cold cash to not dig up turtle nests. And if the hatchlings successfully emerge from their eggs at the end of their 45-day gestation period, the poachers get paid for their work. This has been called the bonus program.

Sea turtle conservationists have been quick to criticize the bonus program. Ward’s strategy has been called unsustainable because if the money runs out, the hueveros will return to stealing eggs.

To comprehend the situation Ward is dealing with in Punta Pargos, it’s important to first be aware of the socio-economic woes that plague rural, coastal villages in Costa Rica in general. Local coastal communities made up of artisanal fishermen; often struggle to feed their children and grandchildren because of the overexploitation of fisheries stocks. Ward believes that the real stewards of this country’s marine fauna, should be the Costa Rican men, women, and children who live out their days on these beaches. But after nightfall, the beaches around Punta Pargos can be a rough place as poachers are a common site, walking the sands in search of turtle tracks…

Photo Source: Dave Sherwood

The extent that arribadas contribute to the population status of Olive Ridleys, creates debate among scientists, locals and sea turtle conservationists. Many believe that the massive reproductive output of these nesting events is critical to maintaining populations, while others maintain that traditional arribada beaches fall far short of their reproductive potential and are most likely not sustaining population level. While biologists have not demonstrably proven that the egg harvesting improves hatchling success, it has been shown that the Ostional nesting turtle population is stable or growing at the site, and other beaches along the coast. Is that a direct result of this program, or of a larger consensus and agreement on bans on turtle fishing and egg collecting worldwide?

Ostional state of affair shows that in an attempt to successfully protect the environment and or a species, derogatory status and gross exemptions to internationally accepted concepts and laws, might obviously not be the most appropriate answer. Furthermore, the status of legal exception unintentionally emphasizes and aggravates a pre-existing problem, on an environmental, economical and human points levels. A global approach and view on the subject appears a lot more appropriate. In this very case, forbidding sea turtles eggs harvesting once and for all, internationally, with no derogatory status. Isolationism is not a sustainable answer to global conservation.

Even though the natural arribada scenario, which is the very keystone of the Ostional legal egg harvesting exception, may seem “maladapted” at first, arribada beaches often realize a small hatch success in proportion, yet the Olive Ridley is the most numerous sea turtle species in the world. This in itself clearly reflects a successful, natural evolutionary strategy within the species!

Ridley turtles’ arribadas nesting do occur on many other beaches throughout the world and, for that matter, none other countries have regulated the Nature’s way…

References and Sources

- NPR : John Burnett, Costa Rican Villagers Sell Turtle Eggs to Save Sea Turtles, but Feud with Scientists

- Costa Rican Conservation Network : Sea Turtles Eggs

- AM Costa Rica Newspaper : 10-26-2010, Dennis Rogers “Ostional turtle egg hoax now comes in many languages”

- Tico Times Directory, Costa Rica : 10-05-2010, “Poaching of Costa Rica Sea Turtle Eggs”

- Costa Rica Turtles : Olive Ridleys and Arribadas

- Duke University, Dr Lisa Campbell : Politics and Practice of Sea Turtle Conservation

- Dr Lisa Campbell’s Report : Sea Turtle Eggs Harvesting in Ostional, Ten Years Later

- Nicoya Peninsula : Ostional Reserve

- University of Michigan : Ostional Project

- Sea Turtles Conservation : Ostional Restoration Project

- Save-a-Turtle : No Shame For Costa Rica

- NPR : Endangered Sea Turtles Return To Mexico’s Beaches

- WWF: Tortuguero, Costa Rica

- The New York Times : Turtles Are Casualties of Warming in Costa Rica

- Dave Sherwood : Photos Gallery