By William J. Neal and Orrin H. Pilkey

Among the world’s most remote beaches are those that line the 62 barrier islands of Colombia’s Pacific Coast. Only two roads lead over the Andes to access points from which the islands and their few, very small, subsistence coastal villages can be reached by boat.

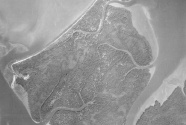

The largest community is the port city of Buenaventura (population ~325,000), well inland at the head of Bahia de Buenaventura, with boat access to the local tourist village of La Bocana at the mouth of the bay. Near this village are small headland beaches, and across the mouth of the bay are the barrier-island beaches on El Soldado and Santa Barbara islands.The only other coastal city on the Pacific Coast of Colombia is Tumaco (population 90,000) near the border with Ecuador. There are a number of small villages on the islands, most with populations of a few hundred.

The origin and character of these beaches are representative of much of Colombia’s Pacific Coast, and their near-natural state means that island and beach dynamics have been little influenced by humans. This character and their location on a tectonically active plate boundary are what led us to make coring expeditions to the islands in search of historic tsunami deposits.

Located just north of the Equator, the islands are covered by tropical rainforest and backed by extensive mangrove swamps, rather than the more familiar salt marshes of mid-latitude barriers. Rainfall here is about 200 inches per year, and on the nearby crest of the Andes, 25 miles from the coast, as much as 300 inches per year. The islands formed on the edge of the narrow coastal plain adjacent to the Northern Andes.

The sand supply for the beaches comes from numerous short streams that feed large volumes of sediment directly to the inlets and thence to the beaches. The immediate Andes sediment source for the beaches is reflected in the color and composition of the sand. The fine-to-medium sand is dark green-to-gray with white specks of shell fragments. The sand is well sorted, that is, there is little variation in grain size on the beaches, except in the form of occasional shell lags. The dark color is due to the dominance of sand-sized rock fragments derived from volcanic and metamorphic rocks. In addition, the sand contains abundant dark heavy minerals such as magnetite.

Tiny mica flakes are also abundant; the flat, glassy mineral grains provide the beach with a beautiful reflective sparkle on sunny days. The presence of mica is an indication that the sand has not been transported far or weathered for very long.

The beaches of the Pacific coast of Colombia are, for the most part, peaceful, quiet, pristine and stunning in their beauty. The quiet is usually broken by birdcalls from the jungle and countless splashing, diving pelican.

—William J. Neal and Orrin H. Pilkey

Beach sand composed of abundant rock fragments and diverse minerals is an indication of immaturity. Mature beach sand such as that on Moroccan and southeastern U.S. beaches has generally lost many of its original and more unstable minerals from the source rocks except for the very stable quartz and feldspar grains and is light colored. To achieve such maturity may take millions of years.

Apparently there is a local belief that the black sand has some therapeutic effect. We watched an old man being buried by his friends as he lay on his back in a shallow ditch. He held an umbrella in his hand to ward off the rain on his still exposed head. He claimed that occasional burial in beach sand helped reduce the aches and pains from his arthritis.

The tidal amplitude here is close to 4 meters, the presumed upper limit for barrier island formation. “Dry” beach width (above the high-tide line) is narrow (tens of feet), and the high tidal range and frequent rainfall keep the beaches wet. Beach sediment is transported by longshore currents, and spits are common at the ends of the islands. Strong tidal currents carry sand out to form horn-like sand bar tidal deltas that extend far seaward from the ends of barrier islands adjacent to large inlets. These submerged ebb-tidal deltas are a navigational hazard even for the ubiquitous dugout canoes with Yamaha outboard motors. Dugout canoes are now manufactured in lumberyards.

Although storms here on the Equator are infrequent, short-term fluctuations in sea level do occur, particularly during times of El Niño when the spring high tides are at a maximum, and during which beach erosion is common (as much as 3 feet of beach retreat on a single tidal cycle). Longer-term erosion is due in part to the global sea-level rise and can be estimated from air photo studies, as well as from field evidence such as stands of dead mangrove trees being actively eroded. With the exception of the accreting spits at the end of the island, from 1961 to 1992 (dates of available air photos) El Soldado showed an average rate of erosion of 16 ft/yr, maintaining the concave seaward shape of its coast. During the same time interval, Santa Barbara Island eroded at even higher rates along its southern shore (up to 27 ft/yr), while accreting at about 33 ft/yr along its northern reach, with an even higher rate in the spits.

On average, it is likely that sea level rise is quite rapid here. Apparently, as the forces of colliding plates cause the Andes to rise, the coastal margin, including the barrier islands and beaches, subsides. Subsidence events are usually accompanied by earthquakes. The Tumaco Earthquake of 1979 caused one 50-mile-long coastal segment to subside as much as 5 feet overnite, resulting in significant and sudden beach retreat. This earthquake also caused a tsunami that resulted in 220 deaths and significant damage to the village of San Juan de la Costa.

When storms do occur, particularly at high tide, these low islands are easily over-washed, as there are no significant beachfront dunes to block the path of storm waves. Perhaps the lack of dunes occurs because the beach sand is continually wet, and sand does not readily blow landward to form dunes. Countering this is the fact that we could feel sand on our legs on windy days, indicating that sand is being transported by wind. J.R.L. Allen, British sedimentologist, made the same observation on the tropical beaches of the Niger Delta barrier islands and was puzzled about the lack of dunes there.

The most serious “fly in the ointment” is trash (garbage), lots of it, at least on the beaches closest to the entrance to Buenaventura Bay. The problem is that some residents of Buenaventura dump their refuse in the bay and when the winds and tides are just right, the cans, bottles and plastic float away to land on the nearest beaches. In recent years, La Bocana and the associated tourist beaches have been kept cleaner by regular trash removal, in an effort to encourage ecotourism.

The beaches of the Pacific coast of Colombia are, for the most part, peaceful, quiet, pristine and beautiful. The quiet is usually broken by birdcalls from the jungle and countless splashing, diving pelicans in numbers far larger than we have seen elsewhere. The Colombian coast and its beaches are stunning in their beauty.

References

Correa Arango, I.D. and Restrepo Angel, J.D., 2002, Geologia y Oceanografia del Delta del Rio San Juan: Litoral Pacifico Colombiano. Fondo Editorial Universidad-EAFIT, Medellin, Colombia, 221p.

Martinez, J.O., Gonzalez, J.L., Pilkey, O.H. and Neal, W.J. 1995. Tropical Barrier Islands of Colombia’s Pacific Coast: Journal of Coastal Research, v 11, p 432 – 453.