By Joe Kelley, University of Maine

Jasper Beach takes the breath away from a first-time visitor. It is located in remote, “Downeast” Maine, USA, at the end of a 10 km (6 miles) peninsula (Figure 1).

The area is very rural with only a few fishing villages, though in recent years, grand vacation homes have sprung upon on some nearby rocky cliffs. As a measure of its remote nature, the 800 m long gravel beach and much of a nearby forested, rocky peninsula was available for less than $50,000 20 years ago. Fortunately, the town of Machiasport, ME bought the beach as a park, and it is free to visit. So lucky for us all!

Jasper Beach is composed of red-colored gravel. Though not “true” Jasper (a silica-rich stone with some iron in it), the fine-grained red volcanic rock polishes well and the long spit gleams in the morning light (Figure 2).

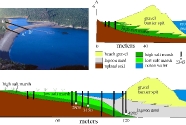

On its extreme western end an eroding bluff of glacial material provides an obvious source of gravel for the beach (Figure 3).

The stones that fall from the bluff range up to 10 cm in length (5 inches), but many sizes occur together near the source. Waves take the eroded material to the east and progressively break the stones down as they travel. About 500 m away from the bluff, there is enough sand in the upper beach to trap rainwater and permit sand dune plants to live. By the eastern end of the strand, the beach material is a mix of fine gravel and sand.

Jasper Beach has a vertical dimension that is not seen in typical sandy beaches. The tides in the area are up to 4.25 m (14 feet) and the beach extends steeply upward for another 4 m (Figure 4).

This high pile of gravel is eroded by waves in winter storms and several erosional steps, or storm berms, are typically cut into the seaward side of the beach. On the landward edge, gravel thrown up by storms surrounds alder and spruce trees, marking the landward advance of the barrier spit. Rising sea level will continue to drive the beach landward over a salt marsh and lagoon, but here there is so little development that it is of no concern.

Other evidence for rising sea level can be seen on low tide at Jasper Beach. As the ocean has risen and driven the immense pile of gravel landward, the beach has rolled over salt marsh and upland plants. Spruce stumps still rooted in soil and overlain by salt marsh peat are exposed at the lowest part of the beach. Geologists from the University of Maine have radiocarbon-dated these and drilled cores through the nearby lagoon to determine the age of the beach (Figures 5, 6).

For more than 4,000 years, Jasper Beach has protected a salt marsh and maintained a lagoonal ecosystem.

Though remote, there are signs of human activity around Jasper Beach. On nearby Howard Cove Mountain, an abandoned distant early warning (DEW) radar station (Figure 4) reminds us of the Cold War.

Fishing weirs (Figure 7) were also a part of the beach when fish abounded in the Gulf of Maine and canneries employed people in Machiasport. These are no longer used, however, and Jasper Beach is largely just a great place to walk and watch Bald Eagles. Unfortunately, a new human activity has appeared on Jasper Beach, one sadly prevalent in rural areas: beach mining. No one will say who takes the red stones from the beach, but a large borrow pit scars the beach near the parking lot (Figure 8).

The State is aware of this robbery and hopefully the guilty, who presumably sell their wares as jewelry to tourists, will be found.

A final note on the unique nature of Jasper Beach is the audio component. Wave after wave rushes in and out and moves the stones back and forth with a rumbling sound. This is so peaceful in the summer; one can scarcely imaging the sound in a winter storm!