Norma Longo, NSOE, Duke University Durham, North Carolina and Wayne Ranney Geologist, Author, Flagstaff, Arizona

Not far north of the city of Dunedin is Koekohe Beach, a long, sandy beach on the east coast of the South Island of New Zealand (Figure 1). If you take the stairs from the visitors’ center/gift shop and parking lot down to the beach, you’ll see a surprising and spectacular sight. This beach is famous for its extraordinary boulders, the Moeraki Boulders, found along its length (Figure 2). The mysterious, legendary boulders come in a variety of sizes and number more than seventy, nearly all fully round, looking like big beach balls waiting for a game. Some are coated with shells of marine creatures such as mussels (Figure 3). The largest boulders are said to weigh several tons and measure more than two meters in diameter (Figure 4).

Geologically, the boulders are septarian concretions, formed in ocean waters, composed of calcite-cemented marine mud, with cracks or septarian veins primarily filled with calcite crystals that precipitated from circulating liquids; some veins include small amounts of quartz and ferrous dolomite. The flat-lying sediments that encase the concretions seem to have once “traveled through the spheres,” documenting that the layers predate concretion formation. While the mineral veins create interesting designs on the outer surfaces of the concretions, some of the boulders have weathered and broken apart, revealing the minerals in the interior core (Figures 5a, 5b). Many aspects of concretion formation remain unclear, but normally concretions form by cementation around some kind of nucleus, for example, a bit of shell or bone.

The seaweed-and-driftwood-strewn beach is nearly flat and consists of a fine-grained, muddy, beige sand, sloping very gently away from the Paleocene mudstone cliffs of the Moeraki Formation behind (Figures 6, 7). Wave action shifts the sand frequently, partially covering, then uncovering, the boulders (Figure 8). The best time to view the boulders is near or at low tide, when you can walk all around them, climb on them, and study them (Figures 9a, 9b).

These concretions formed on an ancient seafloor around 60 million years ago. Boles, et al. (1985) estimated that the Moeraki Formation was uplifted 30 million years after deposition, but the growth time of the larger concretions was thought to be about 4 million years. Thyne and Boles (1989) estimated that the Moeraki concretions formed at a depth of about 700 meters. When the concretions were uplifted with the seafloor, the exposed land became what is now the cliff behind the beach, from which the boulders have eroded over time (Figure 10). Along with the boulders resting on the beach, another one remains partially embedded in the cliff sediments, waiting to be eroded out, and one more that is not fully rounded also can be seen in the cliff (Figures 11, 12). There are probably many more concretions of varied sizes that the rising sea will eventually uncover from their burial places in the layers of mudstone.

This natural wonder, the Moeraki Boulders/Kaihīnaki Scenic Reserve, is protected in order to prevent further damage to the remarkable structures (Figure 13). During a visit to view the boulders in 2020, author Longo learned that they are protected because so many of the boulders had been disappearing, an activity that was documented even in the 1800s. In 1848, Mr. Walter Mangell, Government Commissioner for the Settlement of Native Land Claims in the South Island, kept notes during a trip he made to Moeraki and wrote: “Since their discovery, the remarkable character of these septaria has attracted successive generations of visitors, and nearly all the smaller specimens have been removed to adorn(?)* the corners of paths and the grottoes of the suburban villas of the ingenious.”

The legendary grey-brown boulders make the beach a popular tourist attraction, and thousands of tourists trek there for a view. Similar large concretions can be found in other parts of New Zealand, on both the North Island and the South Island; for example, in the Saurian Sands of the middle Waipara River, north of Moeraki, where the spherical calcareous concretions range up to 4.5 meters in diameter, some with marine reptile bones in them. Other concretions are near Katiki Point south of Moeraki and another occurrence is along the northeast coast of South Island, at Ward Beach, where a number of large concretions were uplifted with the seabed during a 7.8 magnitude earthquake in 2016.

Near Koekohe Beach is the fishing village of Moeraki, which has its own beach but no concretions (Figure 14). Numerous boats float peacefully in the pretty harbour (Figure 15), and in the town, which was a whaling station in the mid-1800s, is the Moeraki Tavern that serves fabulous meals (Figure 16). Across the road from the restaurant is a fine monument with four plaques commemorating the founding of Moeraki. Three mark the Moeraki Centenary, December 26th, 1936. One plaque written in Maori reads: “1836, Whakamaharatanga mo te kotahi rau tau o te pa o Moeraki, 1936” (Figure 17), and the second shows the English translation (Figure 18).

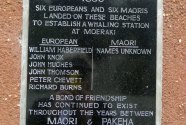

The inscription on the third plaque reads: “Moeraki, Christmas Day 1836, Six Europeans and six Maoris landed on these beaches to establish a whaling station at Moeraki.” The Europeans are listed as William Haberfield, John Knox, John Hughes, John Thomson, Peter Chevett, and Richard Burns. Names of the Maori are recorded as “Unknown” and below the lists is this statement: “A bond of friendship has continued to exist throughout the years between Maori & Paeha. Donated in 1986 to the memory of S.C. Hepburn nee Donaldson” (Figure 19).

The plaque on the fourth face of the monument reads, “1836 This plaque celebrates the 175th Anniversary of the Moeraki Settlement. Donated by the Whitau Whanau. 2011” (Figure 20). Adorning the top of the monument is a medium-sized Moeraki Boulder, probably set in concrete (Figure 21).

*One wonders whether perhaps when Mr. Mangell wrote adorn followed by a question mark, he was subtly saying that the boulders were not a proper adornment for lawns or walkways.

Bibliography

- Boles, J. R., C. A. Landis, and P. Dale. 1985. “The Moeraki Boulders: Anatomy of Some Septarian Concretions.” (May) Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 55(3): 398-406.

- Gregg, D. R. 1978. “Canterbury & Southernmost Marlborough.” In R. P. Suggate (ed.): The Geology of New Zealand: Volume II. Wellington, NZ: E. C. Keating, Government Printer.

- Hamilton, A. 1901. “On the Septarian Boulders of Moeraki, Otago.” Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 1868-1961, Vol. 34, Art. XLIII.

- Hayward, B.W. 2014. “Treasured spheres: protecting New Zealand’s heritage of spherical concretions.” Newsletter no. 12, Geoscience Society of New Zealand, pp 24-30.

- Heyward, Emily. 2018. “Kaikoura Quake Gives Rise to Marlborough’s Own Moeraki Boulders.” January 7. Travel News, Stuff.

- Pearson, Michael J., and Campbell S. Nelson. 2005. “Organic geochemistry and stable isotope composition of New Zealand carbonate concretions and calcite fracture fills.” New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 48 (3): 395-414.

- Prickett, Nigel. 2002. “The Archeology of New Zealand Shore Whaling.” Department of Conservation, Wellington, NZ.

- Ranney, Wayne. 2019. “New Zealand’s South Island.” April 7. Earthly Musings Geology Blog.

- Thyne, G.D., and J.R. Boles. 1989. “Isotopic evidence for origin of the Moeraki septarian concretions, New Zealand.” Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 59 (2): 272-279.

Figure Captions

- Figure 1 – Location map

- Figure 2 – Koekohe Beach and Moeraki Bouldersv

- Figure 3 – Mussels on Moeraki Boulder

- Figure 4 – Moeraki Boulders on Koekohe Beach

- Figure 5a – View of the beach and sea cliff

- Figure 5b – Inside a Moeraki Boulder. The septaria (cracks) are composed of calcite that has grown in the voids.

- Figure 6 – Muddy sands of Koekohe Beach

- Figure 7 – Koekohe Beach and sea cliff

- Figure 8 – Boulders half-covered by sand

- Figure 9a – Author perched on the largest boulder

- Figure 9b – Tourist contemplating boulders

- Figure 10 – Moeraki Formation sea cliff, seaweed and driftwood

- Figure 11 – Author Ranney next to one nodule still in place within the mudstone of the sea cliff.

- Figure 12 – Concretion not fully rounded, still embedded in cliff sediments.

- Figure 13 – Moeraki Boulders/Kaihīnaki Scenic Reserve sign

- Figure 14 – The beach at the town of Moeraki

- Figure 15 – View of Moeraki Harbour

- Figure 16 – Moeraki Tavern sign

- Figures 17-21 – Moeraki Centenary monument