Excerpt:

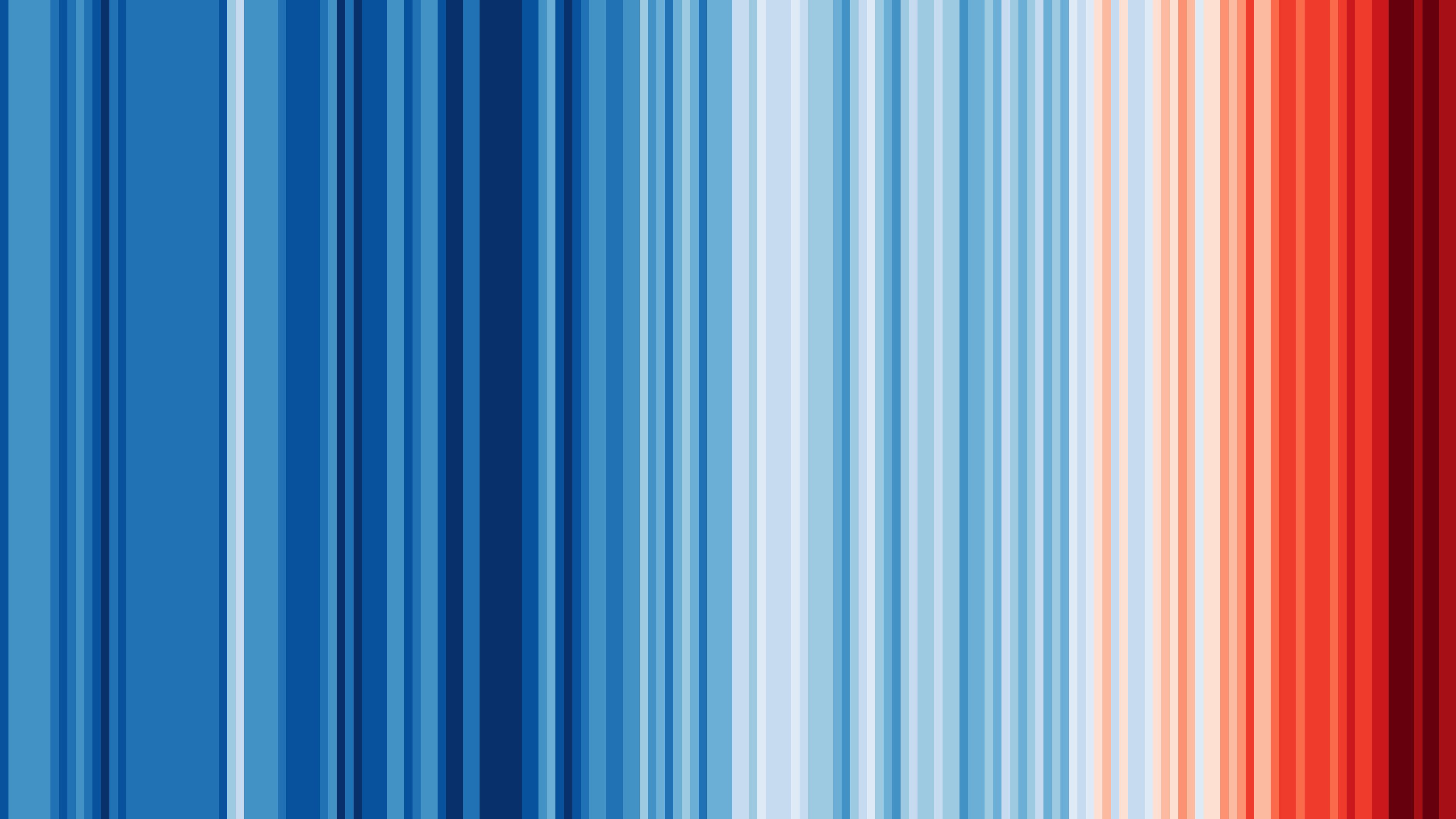

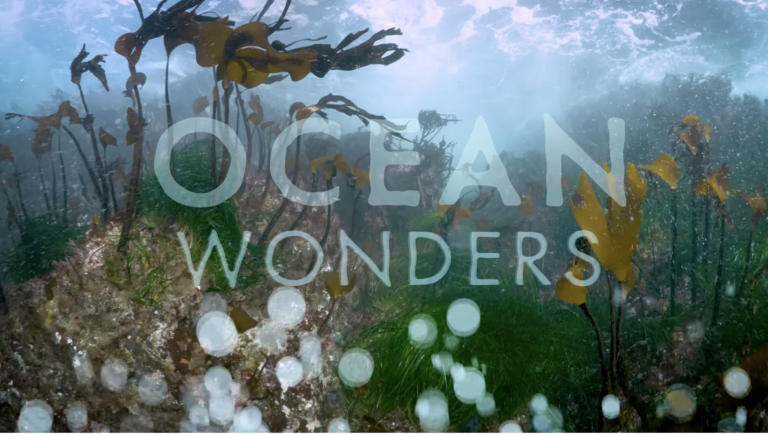

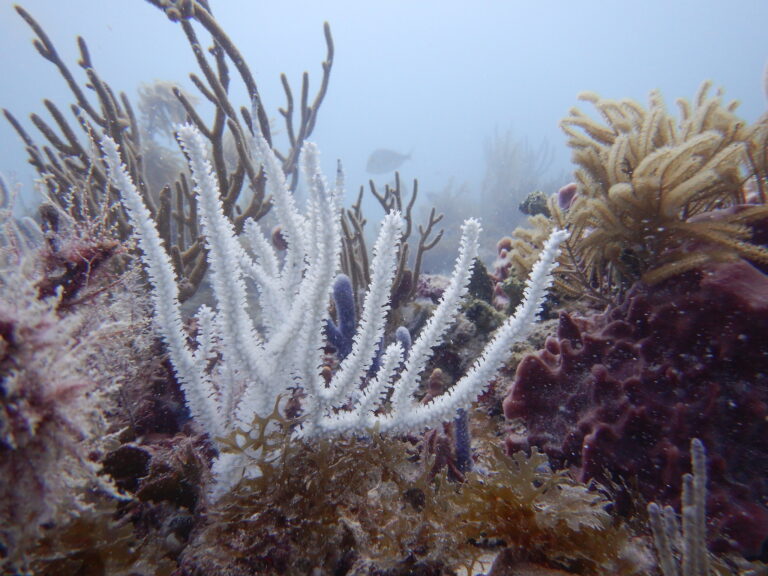

As the early-morning sun rises over the Great Barrier Reef, its light pierces the turquoise waters of a shallow lagoon, bringing more than a dozen turtles to life. These waters that surround Lady Elliot Island, off the eastern coast of Australia, provide some of the most spectacular snorkeling in the world — but they are also on the front line of the climate crisis, as one of the first places to suffer a mass coral bleaching event that has now spread across the world.

The Great Barrier Reef just experienced its worst summer on record, and the US-based National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced last month that the world is undergoing a rare global mass coral bleaching event — the fourth since the late 1990s — impacting at least 53 countries.

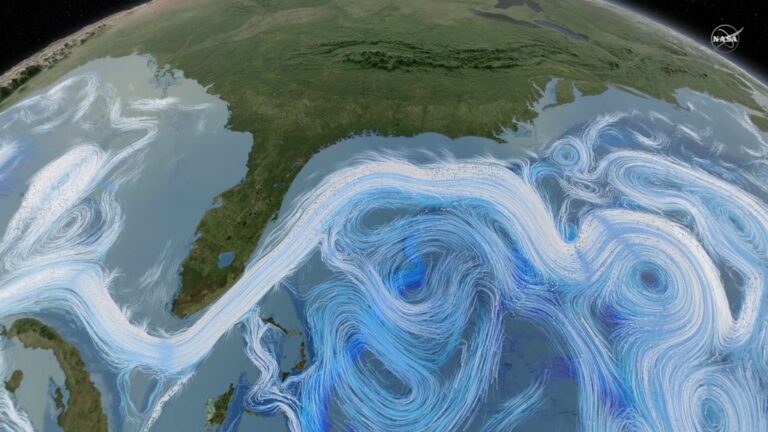

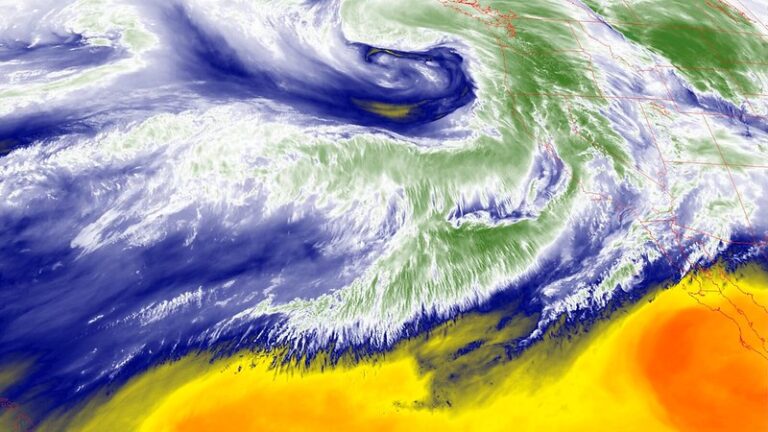

The corals are casualties of surging global temperatures which have smashed historical records in the past year — caused mainly by fossil fuels driving up carbon emissions and accelerated by the El Niño weather pattern, which heats ocean temperatures in this part of the world.

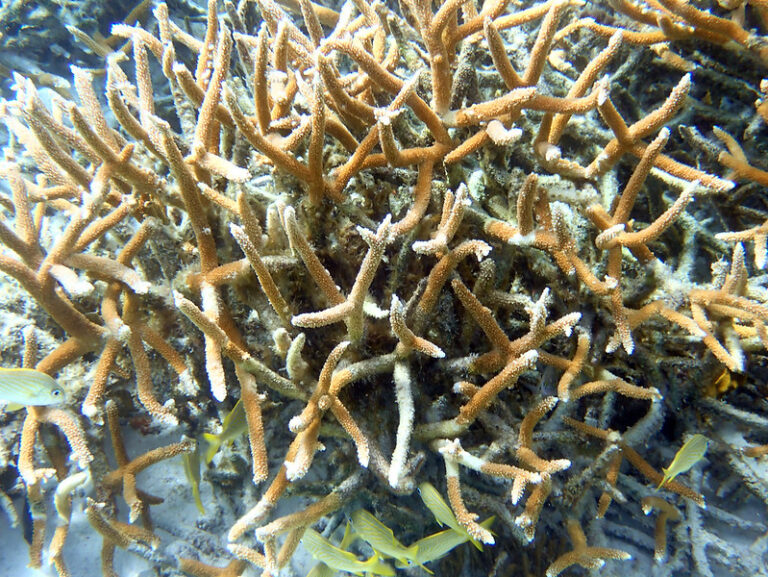

CNN witnessed bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef in mid-February, on five different reefs spanning the northern and southern parts of the 2,300-kilometer (1,400-mile) ecosystem.

“What is happening now in our oceans is like wildfires underwater,” said Kate Quigley, principal research scientist at Australia’s Minderoo Foundation. “We’re going to have so much warming that we’re going to get to a tipping point, and we won’t be able to come back from that.”

Bleaching occurs when marine heatwaves put corals under stress, causing them to expel algae from their tissue, draining their color. Corals can recover from bleaching if the temperatures return to normal, but they will perish if the water stays warmer than usual.

“It’s a die-off,” said Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, a climate scientist at the University of Queensland in Australia and chief scientist at The Great Barrier Reef Foundation. “The temperatures got so warm, they’re off the charts … they never occurred before at this sort of level.”

The destruction of marine ecosystems would deliver an effective death sentence for around a quarter of all species that depend on reefs for survival — and threaten an estimated billion people who rely on reef fish for their food and livelihoods. Reefs also provide vital protection for coastlines, reducing the impact of floods, cyclones and sea level rise.

After taking off from Brisbane just after dawn, our tiny propeller plane skims miles of Queensland coastline before heading north out over the crystal-clear waters of the Coral Sea –— revealing the beauty of this vast reef system beneath its surface.

Our destination is Lady Elliot Island, a remote coral cay perched on top of the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef.

Pilot Peter Gash is the island’s leaseholder, and his family has been operating tours to the island for nearly 20 years.

“We made it our life’s work,” Gash said. “My wife and I married, I went and learned to fly airplanes so I could bring people here.”

Gash negotiates his small aircraft through bumpy crosswinds to land safely on the short, grass-covered runway.

Decades ago, the island was a barren landscape devoid of vegetation following years of mining for nutrient-rich seabird waste — known as guano — in the late 1800s.

The Gash family set about bringing this island back to life, planting around 10,000 native species of trees to create a man-made forest and nature reserve, and using solar power, batteries and a water desalination system to support a small eco-tourism resort.

The island is now home to up to 200,000 sea birds, which have helped to regenerate the coral reef fringing the island.

Additional Reading . . .

‘Like wildfires underwater’: Worst summer on record for Great Barrier Reef as coral die-off sweeps planet – CNN World

Rising sea temperatures around the planet have caused a bleaching event that is expected to be the most extensive on record…

Great Barrier Reef’s worst bleaching leaves giant coral graveyard: ‘It looks as if it has been carpet bombed’ – the Guardian

Last month the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority released a report warning that the reef was experiencing “the highest levels of thermal stress on record”. The authority’s chief scientist, Dr Roger Beeden, spoke of extensive and uniform bleaching across the southern reefs, which had dodged the worst of much of the previous four mass bleaching events to blight the Great Barrier Reef since 2016…

Corals are bleaching in every corner of the ocean, threatening its web of life – the Washington Post

First around Fiji, then the Florida Keys, then Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and now in the Indian Ocean. In the past year, anomalous ocean temperatures have left a trail of devastation for the world’s corals, bleaching entire reefs and threatening widespread coral mortality — and now, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and International Coral Reef Initiative say the world is experiencing its fourth global bleaching event, the second in the last decade…

ABC News – Australia (04-15-2024):

‘Moved to tears’: The hottest year on record unleashes a mass coral bleaching tragedy

PBS NewsHour (04-18-2024):

Record-breaking ocean heat triggers massive coral reef bleaching

Island News (04-17-2024):

Record heat stress hits Great Barrier Reef: Experts warn of serious bleaching

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Excerpt:

2,000 people were stranded recently when a chunk of Highway 1 fell into the sea near Big Sur. The solution may lurk in an unlikely place: Yorkshire

The first time Gary Griggs drove the Pacific Coast Highway, it was the early 1960s. He was a college student heading north to San Francisco for the weekend with his girlfriend in an elderly Volkswagen van, occasionally getting out to give it a push.

“At that point not that many people drove the highway,” Griggs, who is now an expert on coastal erosion, said. Near the southern end, where the highway begins its run up the edge of a furious ocean, atop cliffs and beneath steep mountains, “people coming down that had just made it would wave to you, [as if to say:] ‘Good luck!’” he said.

Since then generations of engineers have strengthened it with buttresses, bridges and tunnels, and it has become one of the most famous roads in the world. Yet driving it can still be a dicey proposition and there are now questions over whether the highway can survive at all.

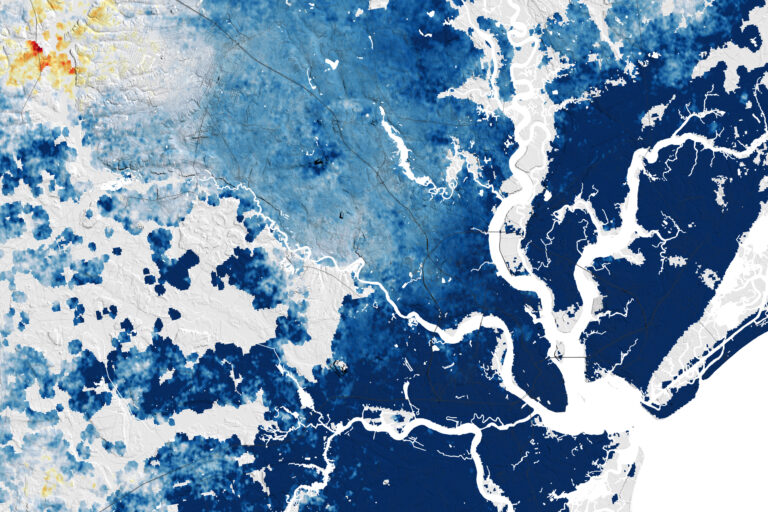

Last Saturday, after days of heavy rain, a chunk of the road in Big Sur vanished down a cliff side into the sea, and up to 2,000 people were stranded. Since then the California department of transportation has been leading twice-daily convoys of motorists who wish to make their way south, heading along a single lane past the place where a large bite of tarmac is missing.

There is one convoy at 8am and one at 4pm, said Nicholas Pasculli, a spokesman for Monterey County. Over the weekend the county opened a shelter in a conference centre in Big Sur, where stranded people could stay. About 450 people stayed in camp grounds, he said. “And of course a lot of people camped out in their cars overnight.”

Convoys to get people in and out began on Sunday and will continue, “weather permitting”, he said. “Right now the weather is great,” he said. But later in the week, particularly on Friday, it looks like rain.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, said it was only the latest and not the largest piece of the highway to go missing in recent years. “It’s just that it occurred at a pinch point,” he said. “Would you want to drive the other lane that hasn’t yet slipped into the ocean? It’s correctly viewed as a risky proposition.”

A relatively small population lives along the road, and some are multimillionaires. But there are also, he said, “folks who are not wealthy who live in the canyons that come off the highway”. And “for some of these places there isn’t alternative access by road. There have been periods in the last decade where people have had to hike out.”

It offers a more dramatic and picturesque vision of the knotty choices that will face millions more in big coastal cities. “It’s a major state highway that runs along huge cliffs over the water,” he said — they are under constant assault by the ocean.

“Those cliffs are often the first thing the waves hit after travelling from the south Pacific ocean thousands of miles away,” he said. On the other side of the road, “the Big Sur mountains rise directly out of the ocean thousands of feet into the air”, lifting the rivers of cloud sweeping in off the Pacific and prompting rain. The road would be in a delicate situation “even if there was no climate change”, he said. “That’s how geography works.”

Even as climate change is causing heavier rain and rising sea levels, Swain does not like the idea of abandoning the road. “It’s not really clear what we should do about it,” he said…

Additional Reading:

Why Highway 1 Near Big Sur Is Always Collapsing Into The Ocean – LAist

About 2,000 motorists, mostly tourists, were stuck in the area on Saturday night after a section of Highway 1 fell into the ocean. No injuries were reported….

Travelers Stranded by Highway Collapse Begin to Leave Big Sur – the New York Times

About 2,000 motorists, mostly tourists, were stuck in the area on Saturday night after a section of Highway 1 fell into the ocean. No injuries were reported….

California’s Highway 1 road conditions will only get riskier, experts say – the Guardian

Chunk of famed route crumbled into sea causing another closure, and conditions are expected to only worsen with climate crisis…

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Beaches | Coasts of the Month . . .

Photos of the Month . . .

In anticipation of a live forum at the Pedro Point Firehouse in Pacifica California with Rosanna Xiaa, a Los Angeles Times environmental reporter and author of “California Against the Sea,” and coastal geology expert and professor Gary Griggs, held on Sunday, March 3, 2024, Tribune intern and Oceana High School student Tyler Paing, sat down with Griggs to explore the topic of coastal erosion for California and what it means for Pacifica…

CURRENT NEWS + RECENT POSTS

2022 Six Part Series on “Sand Dealers” – Le Monde

Manila Confronts Its Plastic Problem – EOS