Excerpt:

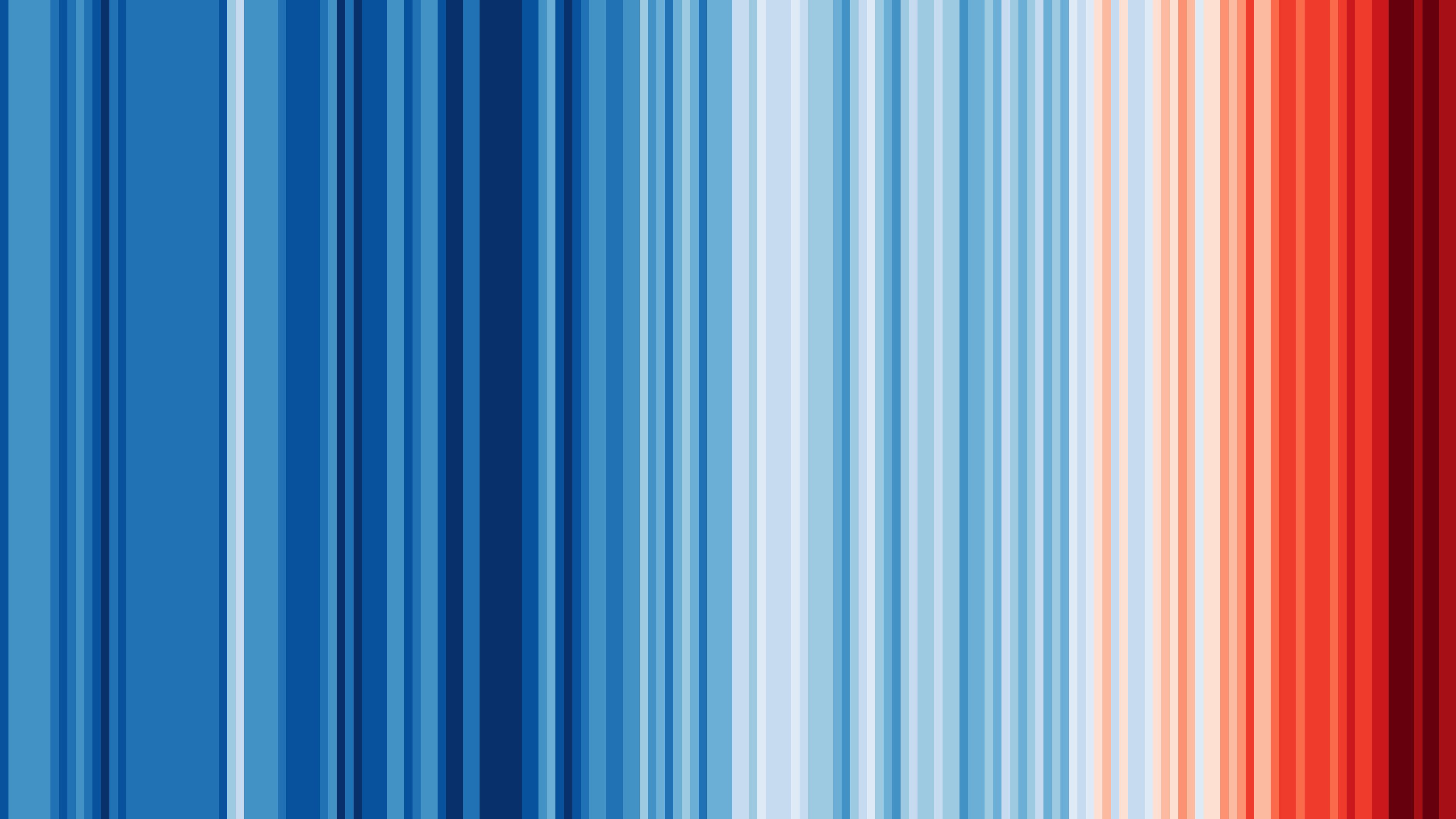

Rising sea temperatures around the planet have caused a bleaching event that is expected to be the most extensive on record.

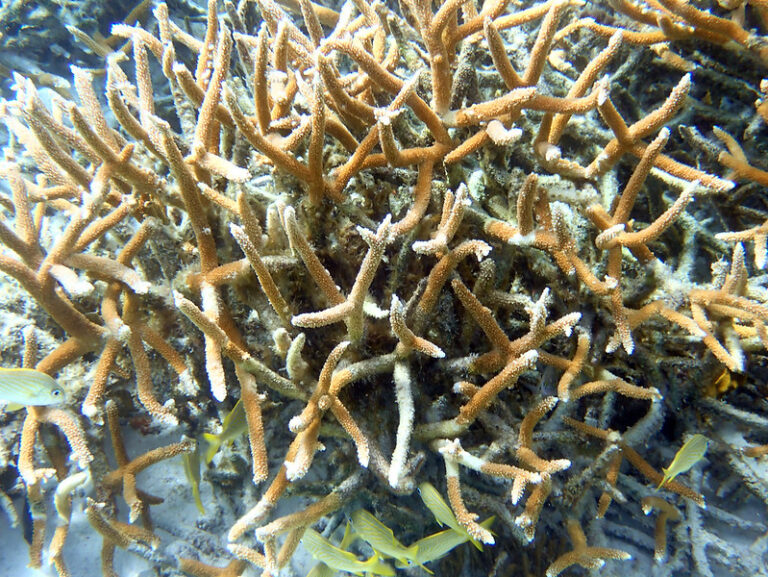

The world’s coral reefs are in the throes of a global bleaching event caused by extraordinary ocean temperatures, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and international partners announced Monday.

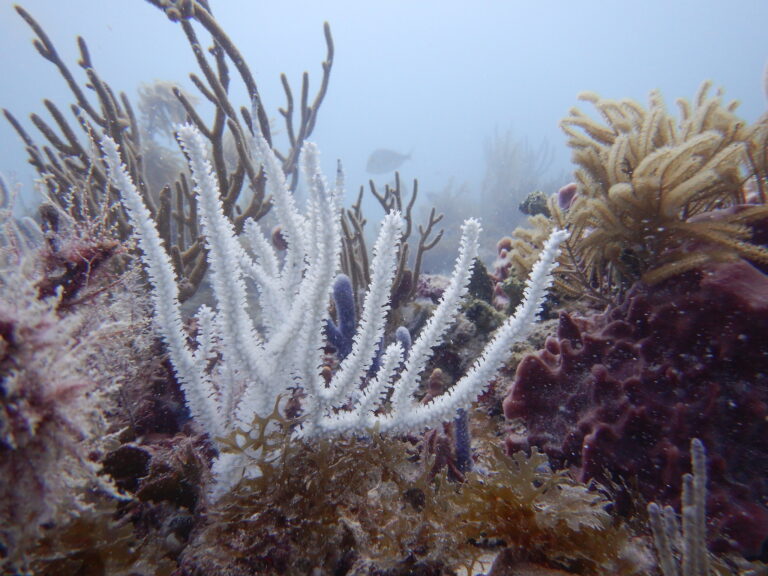

It is the fourth such global event on record and is expected to affect more reefs than any other. Bleaching occurs when corals become so stressed that they lose the symbiotic algae they need to survive. Bleached corals can recover, but if the water surrounding them is too hot for too long, they die.

Coral reefs are vital ecosystems: limestone cradles of marine life that nurture an estimated quarter of ocean species at some point during their life cycles, support fish that provide protein for millions of people and protect coasts from storms. The economic value of the world’s coral reefs has been estimated at $2.7 trillion annually.

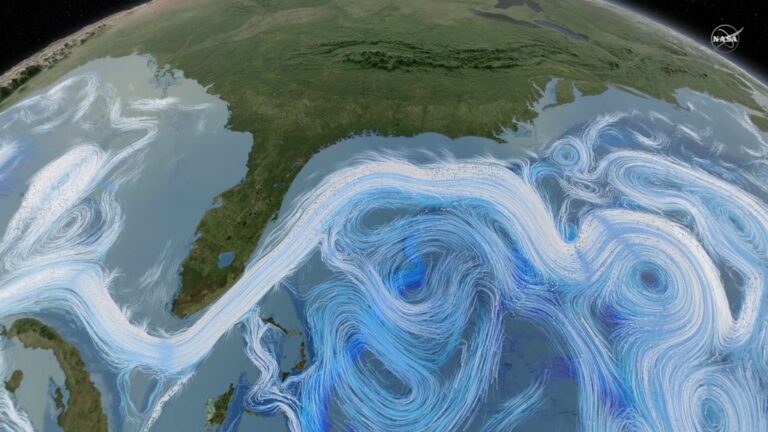

For the last year, ocean temperatures have been off the charts.

Substantial coral death has been confirmed around Florida and the Caribbean, particularly among staghorn and elk horn species, but scientists say it’s too soon to estimate what the extent of global mortality will be.

To determine a global bleaching event, NOAA and the group of global partners, the International Coral Reef Initiative, use a combination of sea surface temperatures and evidence from reefs. By their criteria, all three ocean basins that host coral reefs — the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic — must experience bleaching within 365 days, and at least 12 percent of the reefs in each basin must be subjected to temperatures that cause bleaching.

Currently, more than 54 percent of the world’s coral area has experienced bleaching-level heat stress in the past year, and that number is increasing by about 1 percent per week, Dr. Manzello said.

He added that within a week or two, “this event is likely to be the most spatially extensive global bleaching event on record.”

Each of the three previous global bleaching events has been worse than the last. During the first, in 1998, 20 percent of the world’s reef areas suffered bleaching-level heat stress. In 2010, it was 35 percent. The third spanned 2014 to 2017 and affected 56 percent of reefs.

The current event is expected to be shorter-lived, Dr. Manzello said, because El Niño, a natural climate pattern associated with warmer oceans, is weakening and forecasters predict a cooler La Niña period to take hold by the end of the year.

Bleaching has been confirmed in 54 countries, territories and local economies, as far apart as Florida, Saudi Arabia and Fiji. The Great Barrier Reef in Australia is suffering what appears to be its most severe bleaching event; about a third of the reefs surveyed by air showed prevalence of very high or extreme bleaching, and at least three quarters showed some bleaching.

“I do get depressed sometimes, because the feeling is like, ‘My God, this is happening,’” said Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, a professor of marine studies at the University of Queensland who published early predictions about how global warming would be catastrophic for coral reefs.

“Now we’re at the point where we’re in the disaster movie,” he said…

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Excerpt:

2,000 people were stranded recently when a chunk of Highway 1 fell into the sea near Big Sur. The solution may lurk in an unlikely place: Yorkshire

The first time Gary Griggs drove the Pacific Coast Highway, it was the early 1960s. He was a college student heading north to San Francisco for the weekend with his girlfriend in an elderly Volkswagen van, occasionally getting out to give it a push.

“At that point not that many people drove the highway,” Griggs, who is now an expert on coastal erosion, said. Near the southern end, where the highway begins its run up the edge of a furious ocean, atop cliffs and beneath steep mountains, “people coming down that had just made it would wave to you, [as if to say:] ‘Good luck!’” he said.

Since then generations of engineers have strengthened it with buttresses, bridges and tunnels, and it has become one of the most famous roads in the world. Yet driving it can still be a dicey proposition and there are now questions over whether the highway can survive at all.

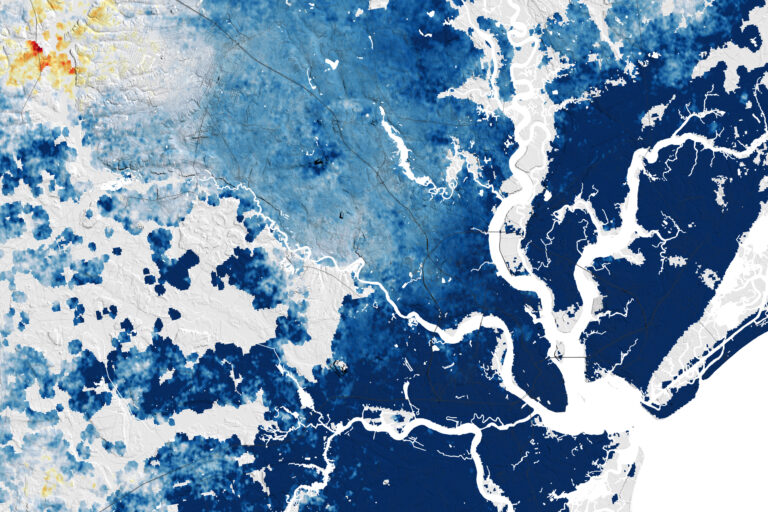

Last Saturday, after days of heavy rain, a chunk of the road in Big Sur vanished down a cliff side into the sea, and up to 2,000 people were stranded. Since then the California department of transportation has been leading twice-daily convoys of motorists who wish to make their way south, heading along a single lane past the place where a large bite of tarmac is missing.

There is one convoy at 8am and one at 4pm, said Nicholas Pasculli, a spokesman for Monterey County. Over the weekend the county opened a shelter in a conference centre in Big Sur, where stranded people could stay. About 450 people stayed in camp grounds, he said. “And of course a lot of people camped out in their cars overnight.”

Convoys to get people in and out began on Sunday and will continue, “weather permitting”, he said. “Right now the weather is great,” he said. But later in the week, particularly on Friday, it looks like rain.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, said it was only the latest and not the largest piece of the highway to go missing in recent years. “It’s just that it occurred at a pinch point,” he said. “Would you want to drive the other lane that hasn’t yet slipped into the ocean? It’s correctly viewed as a risky proposition.”

A relatively small population lives along the road, and some are multimillionaires. But there are also, he said, “folks who are not wealthy who live in the canyons that come off the highway”. And “for some of these places there isn’t alternative access by road. There have been periods in the last decade where people have had to hike out.”

It offers a more dramatic and picturesque vision of the knotty choices that will face millions more in big coastal cities. “It’s a major state highway that runs along huge cliffs over the water,” he said — they are under constant assault by the ocean.

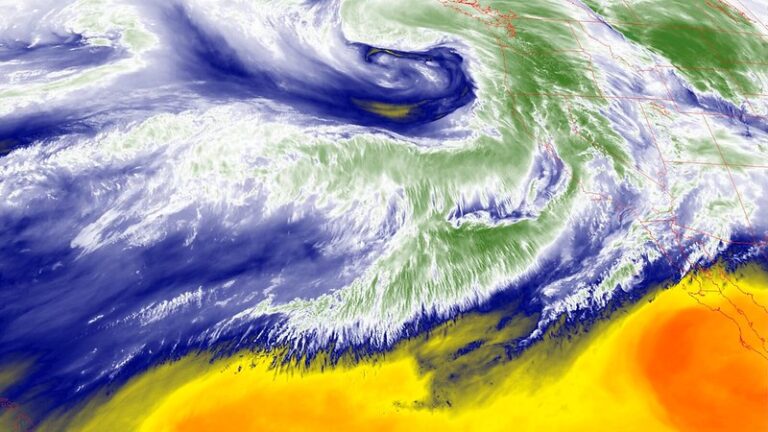

“Those cliffs are often the first thing the waves hit after travelling from the south Pacific ocean thousands of miles away,” he said. On the other side of the road, “the Big Sur mountains rise directly out of the ocean thousands of feet into the air”, lifting the rivers of cloud sweeping in off the Pacific and prompting rain. The road would be in a delicate situation “even if there was no climate change”, he said. “That’s how geography works.”

Even as climate change is causing heavier rain and rising sea levels, Swain does not like the idea of abandoning the road. “It’s not really clear what we should do about it,” he said…

Additional Reading:

Why Highway 1 Near Big Sur Is Always Collapsing Into The Ocean – LAist

About 2,000 motorists, mostly tourists, were stuck in the area on Saturday night after a section of Highway 1 fell into the ocean. No injuries were reported….

Travelers Stranded by Highway Collapse Begin to Leave Big Sur – the New York Times

About 2,000 motorists, mostly tourists, were stuck in the area on Saturday night after a section of Highway 1 fell into the ocean. No injuries were reported….

California’s Highway 1 road conditions will only get riskier, experts say – the Guardian

Chunk of famed route crumbled into sea causing another closure, and conditions are expected to only worsen with climate crisis…

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Beaches | Coasts of the Month . . .

Photos of the Month . . .

In anticipation of a live forum at the Pedro Point Firehouse in Pacifica California with Rosanna Xiaa, a Los Angeles Times environmental reporter and author of “California Against the Sea,” and coastal geology expert and professor Gary Griggs, held on Sunday, March 3, 2024, Tribune intern and Oceana High School student Tyler Paing, sat down with Griggs to explore the topic of coastal erosion for California and what it means for Pacifica…

CURRENT NEWS + RECENT POSTS

2022 Six Part Series on “Sand Dealers” – Le Monde

Manila Confronts Its Plastic Problem – EOS