Excerpt:

Scientists stunned by scale of destruction after summer of storm surges, cyclones and floods

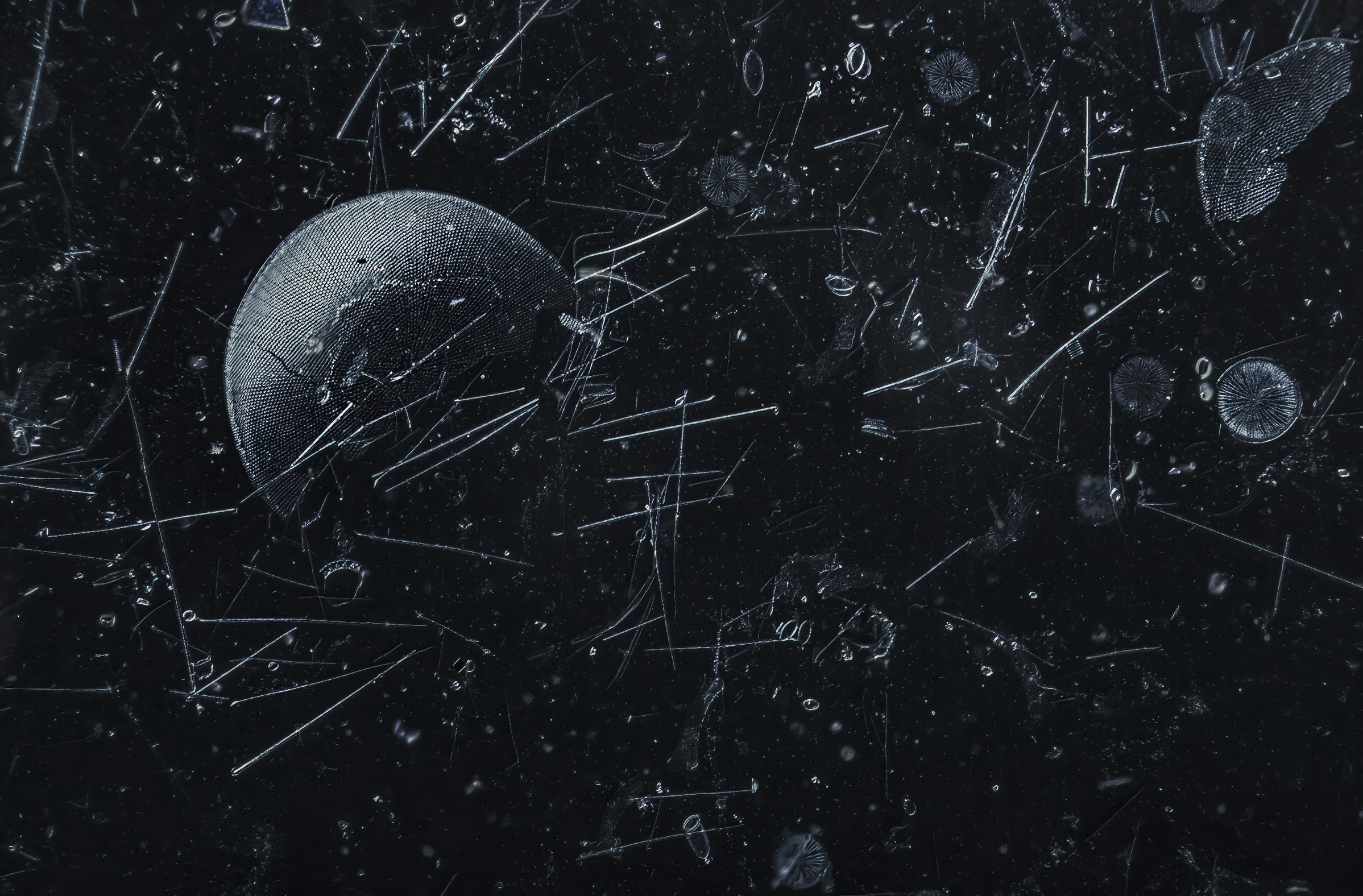

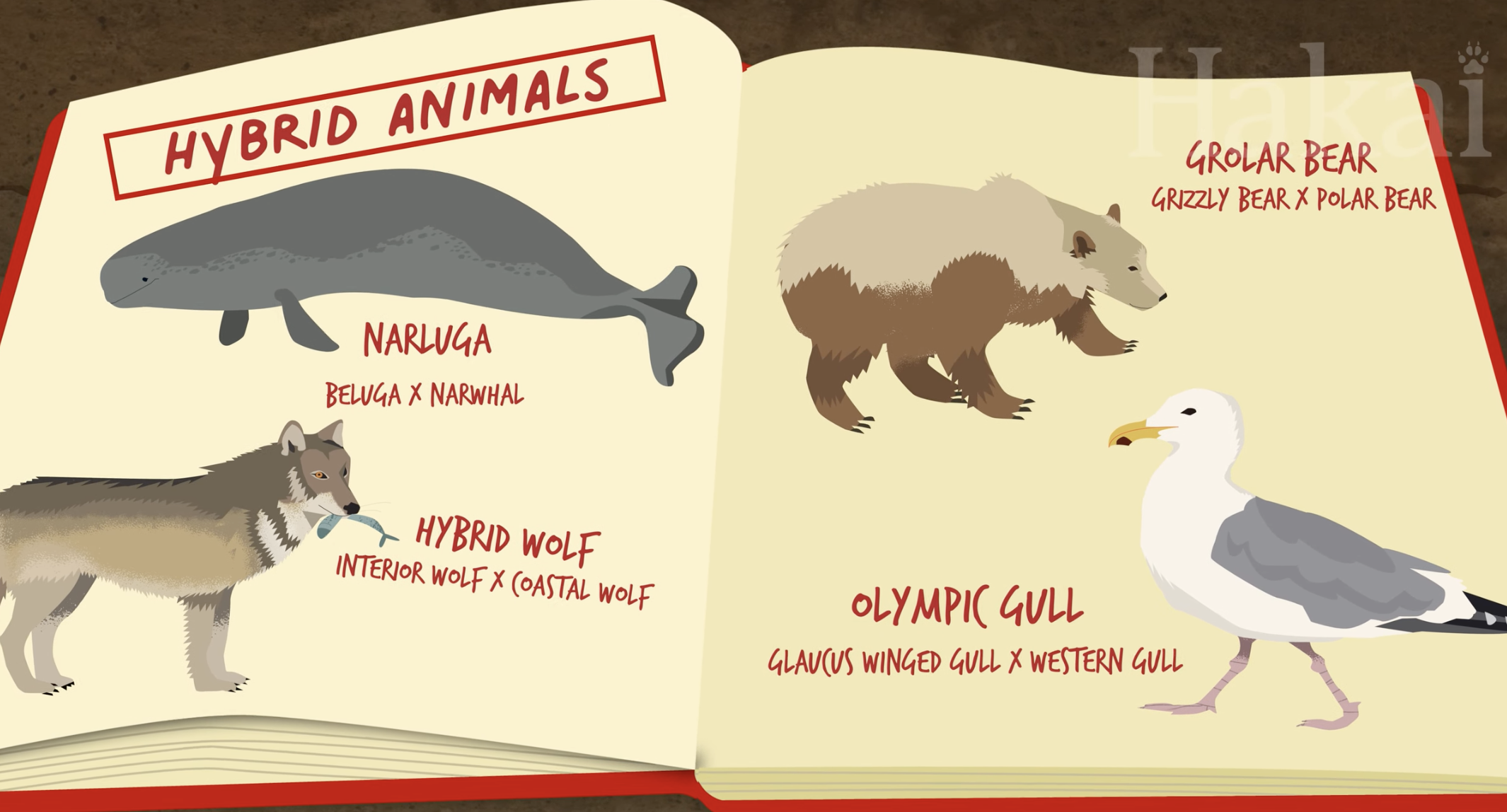

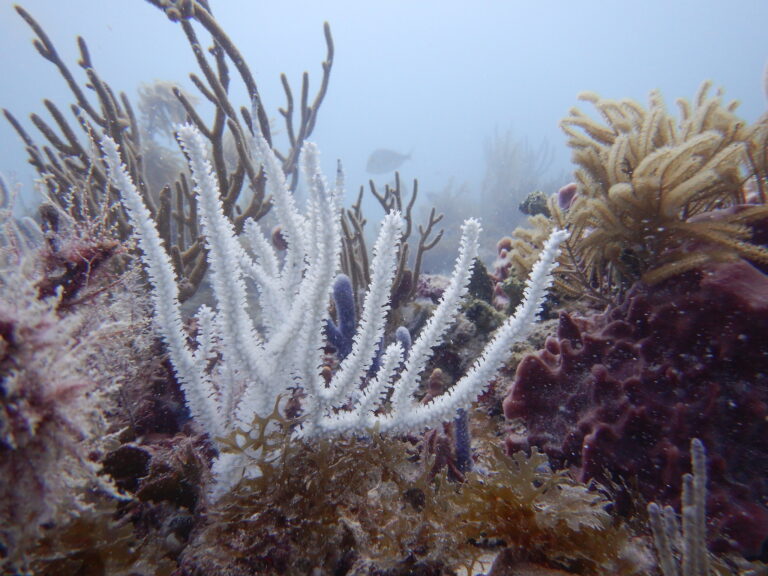

Beneath the turquoise waters off Heron Island lies a huge, brain-shaped Porites coral that, in health, would be a rude shade of purplish-brown. Today that coral outcrop, or bommie, shines snow white.

Prof Terry Hughes, a coral bleaching expert at James Cook University, estimates this living boulder is at least 300 years old.

“If that thing had eyes it could have looked up and watched Captain Cook sail past,” he says, back on the pristine beach of this speck of an island 80km offshore at the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef.

It is not just Heron’s grand old bommie that is freshly bleached. The surrounding tangle of staghorn corals, or Acropora, are splashed in swathes of white, or painted a dappled mosaic of greens and browns that betray the algae and seaweeds growing over the freshly killed coral. Hughes estimates 90% of those branching corals are dead or dying.

Snorkelling above these blighted coral thickets evokes the imagery of forests annihilated by bushfires, or cities obliterated by missiles.

“It looks as if it has been carpet bombed,” says the Greens senator Peter Whish-Wilson, who has accompanied Hughes to Heron. “Like limbs strewn everywhere.”

Even Hughes, a man who has witnessed as much mass mortality of coral as any, looks shellshocked.

The Dublin-born, Townsville-based marine biologist already knew the coral ringing Heron had just experienced its worst recorded bleaching – and that this was no isolated event.

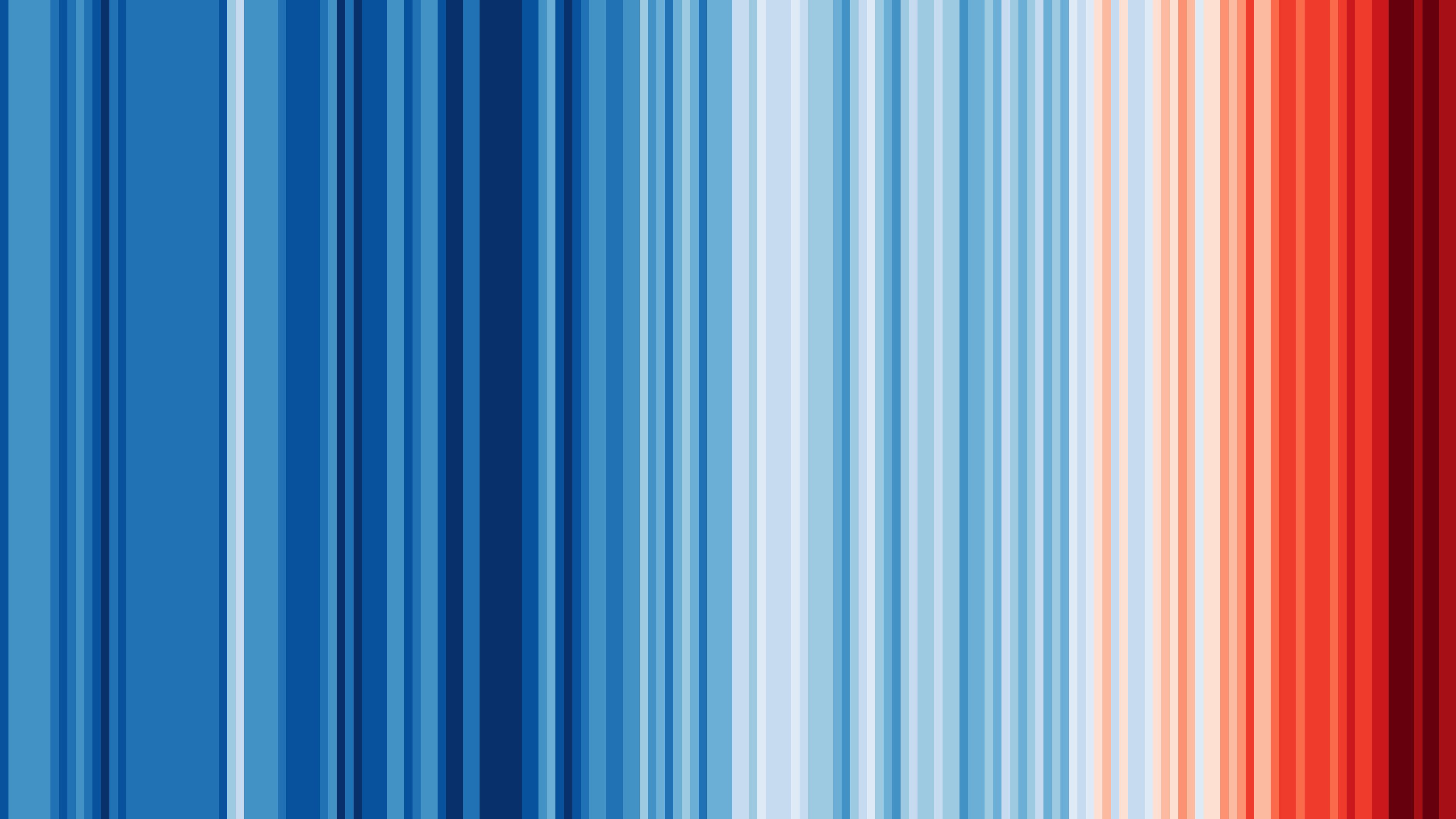

Last month the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority released a report warning that the reef was experiencing “the highest levels of thermal stress on record”. The authority’s chief scientist, Dr Roger Beeden, spoke of extensive and uniform bleaching across the southern reefs, which had dodged the worst of much of the previous four mass bleaching events to blight the Great Barrier Reef since 2016.

Hughes saw in the institute’s aerial surveys results the most “widespread event and severe” bleaching event to date, not just in the south, but across much of the entire system – which stretches 2,300km up the Queensland coast.

But none of these metrics, it seems, could truly prepare him for the act of bearing witness to the unfolding calamity he has dedicated his life to preventing.

“It’s fucking awful,” the softly spoken scientist says, emerging from the ocean. “They said the bleaching was extensive and uniform. They didn’t say it was extensive, uniform and fucking awful.

“It’s a graveyard out there…”

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Excerpt:

2,000 people were stranded recently when a chunk of Highway 1 fell into the sea near Big Sur. The solution may lurk in an unlikely place: Yorkshire

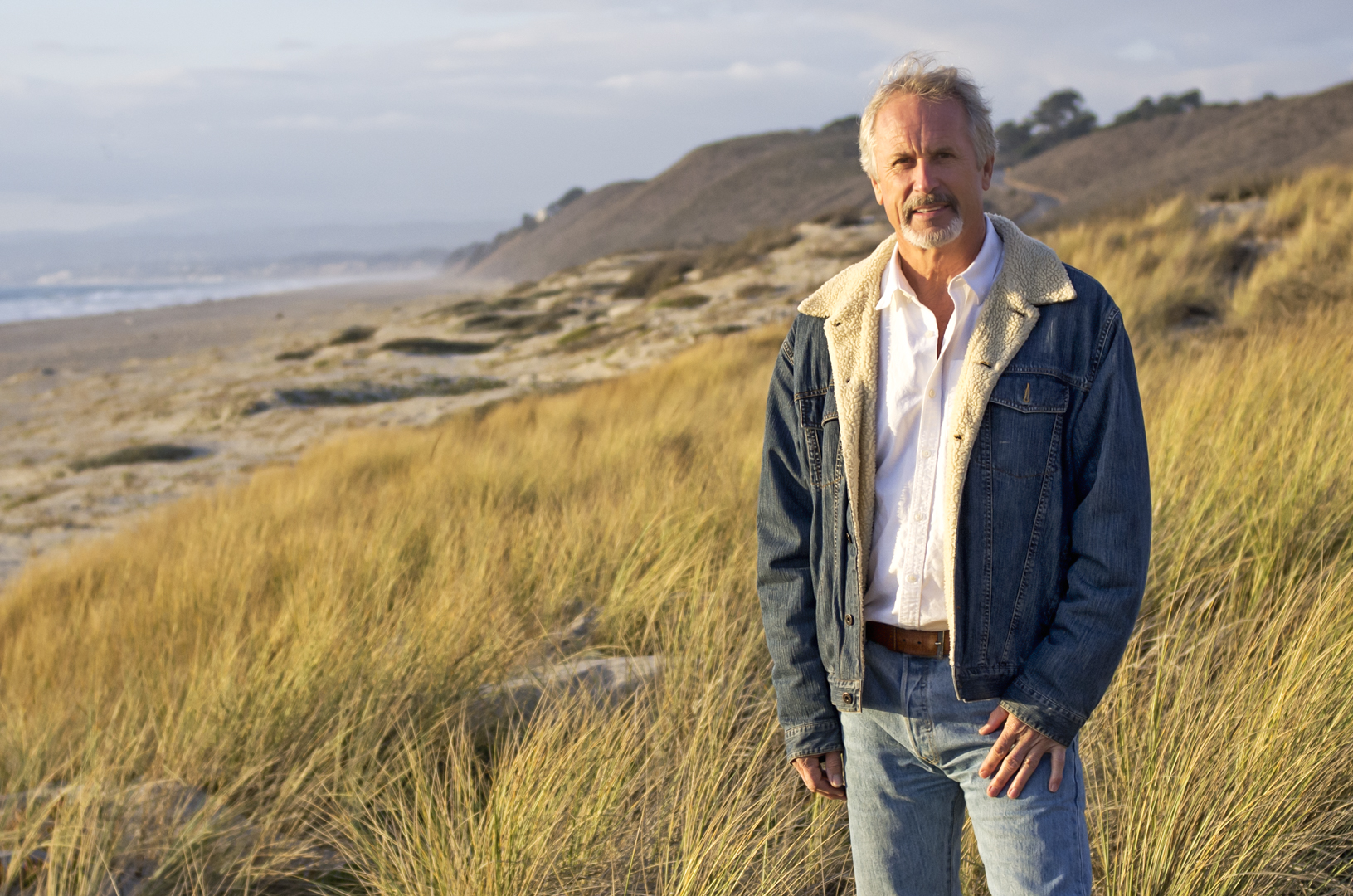

The first time Gary Griggs drove the Pacific Coast Highway, it was the early 1960s. He was a college student heading north to San Francisco for the weekend with his girlfriend in an elderly Volkswagen van, occasionally getting out to give it a push.

“At that point not that many people drove the highway,” Griggs, who is now an expert on coastal erosion, said. Near the southern end, where the highway begins its run up the edge of a furious ocean, atop cliffs and beneath steep mountains, “people coming down that had just made it would wave to you, [as if to say:] ‘Good luck!’” he said.

Since then generations of engineers have strengthened it with buttresses, bridges and tunnels, and it has become one of the most famous roads in the world. Yet driving it can still be a dicey proposition and there are now questions over whether the highway can survive at all.

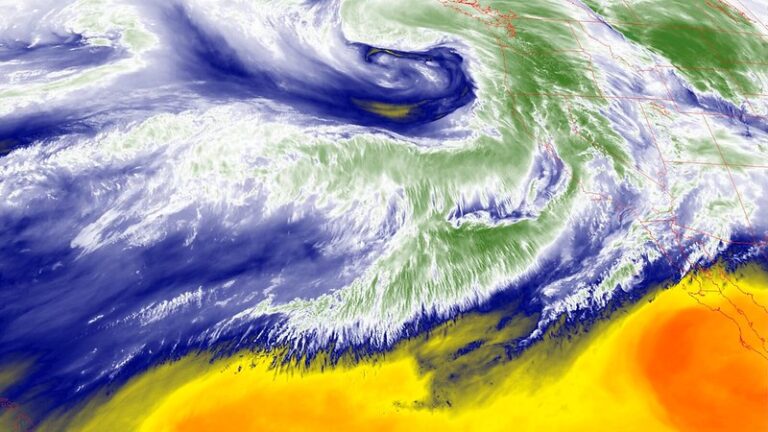

Last Saturday, after days of heavy rain, a chunk of the road in Big Sur vanished down a cliff side into the sea, and up to 2,000 people were stranded. Since then the California department of transportation has been leading twice-daily convoys of motorists who wish to make their way south, heading along a single lane past the place where a large bite of tarmac is missing.

There is one convoy at 8am and one at 4pm, said Nicholas Pasculli, a spokesman for Monterey County. Over the weekend the county opened a shelter in a conference centre in Big Sur, where stranded people could stay. About 450 people stayed in camp grounds, he said. “And of course a lot of people camped out in their cars overnight.”

Convoys to get people in and out began on Sunday and will continue, “weather permitting”, he said. “Right now the weather is great,” he said. But later in the week, particularly on Friday, it looks like rain.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, said it was only the latest and not the largest piece of the highway to go missing in recent years. “It’s just that it occurred at a pinch point,” he said. “Would you want to drive the other lane that hasn’t yet slipped into the ocean? It’s correctly viewed as a risky proposition.”

A relatively small population lives along the road, and some are multimillionaires. But there are also, he said, “folks who are not wealthy who live in the canyons that come off the highway”. And “for some of these places there isn’t alternative access by road. There have been periods in the last decade where people have had to hike out.”

It offers a more dramatic and picturesque vision of the knotty choices that will face millions more in big coastal cities. “It’s a major state highway that runs along huge cliffs over the water,” he said — they are under constant assault by the ocean.

“Those cliffs are often the first thing the waves hit after travelling from the south Pacific ocean thousands of miles away,” he said. On the other side of the road, “the Big Sur mountains rise directly out of the ocean thousands of feet into the air”, lifting the rivers of cloud sweeping in off the Pacific and prompting rain. The road would be in a delicate situation “even if there was no climate change”, he said. “That’s how geography works.”

Even as climate change is causing heavier rain and rising sea levels, Swain does not like the idea of abandoning the road. “It’s not really clear what we should do about it,” he said…

Additional Reading:

Why Highway 1 Near Big Sur Is Always Collapsing Into The Ocean – LAist

About 2,000 motorists, mostly tourists, were stuck in the area on Saturday night after a section of Highway 1 fell into the ocean. No injuries were reported….

Travelers Stranded by Highway Collapse Begin to Leave Big Sur – the New York Times

About 2,000 motorists, mostly tourists, were stuck in the area on Saturday night after a section of Highway 1 fell into the ocean. No injuries were reported….

California’s Highway 1 road conditions will only get riskier, experts say – the Guardian

Chunk of famed route crumbled into sea causing another closure, and conditions are expected to only worsen with climate crisis…

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Beaches | Coasts of the Month . . .

Photos of the Month . . .

In anticipation of a live forum at the Pedro Point Firehouse in Pacifica California with Rosanna Xiaa, a Los Angeles Times environmental reporter and author of “California Against the Sea,” and coastal geology expert and professor Gary Griggs, held on Sunday, March 3, 2024, Tribune intern and Oceana High School student Tyler Paing, sat down with Griggs to explore the topic of coastal erosion for California and what it means for Pacifica…

CURRENT NEWS + RECENT POSTS

2022 Six Part Series on “Sand Dealers” – Le Monde

Manila Confronts Its Plastic Problem – EOS